The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

My debut novel is about the female experience – please don’t reduce it to a ‘sad girl’ cliché

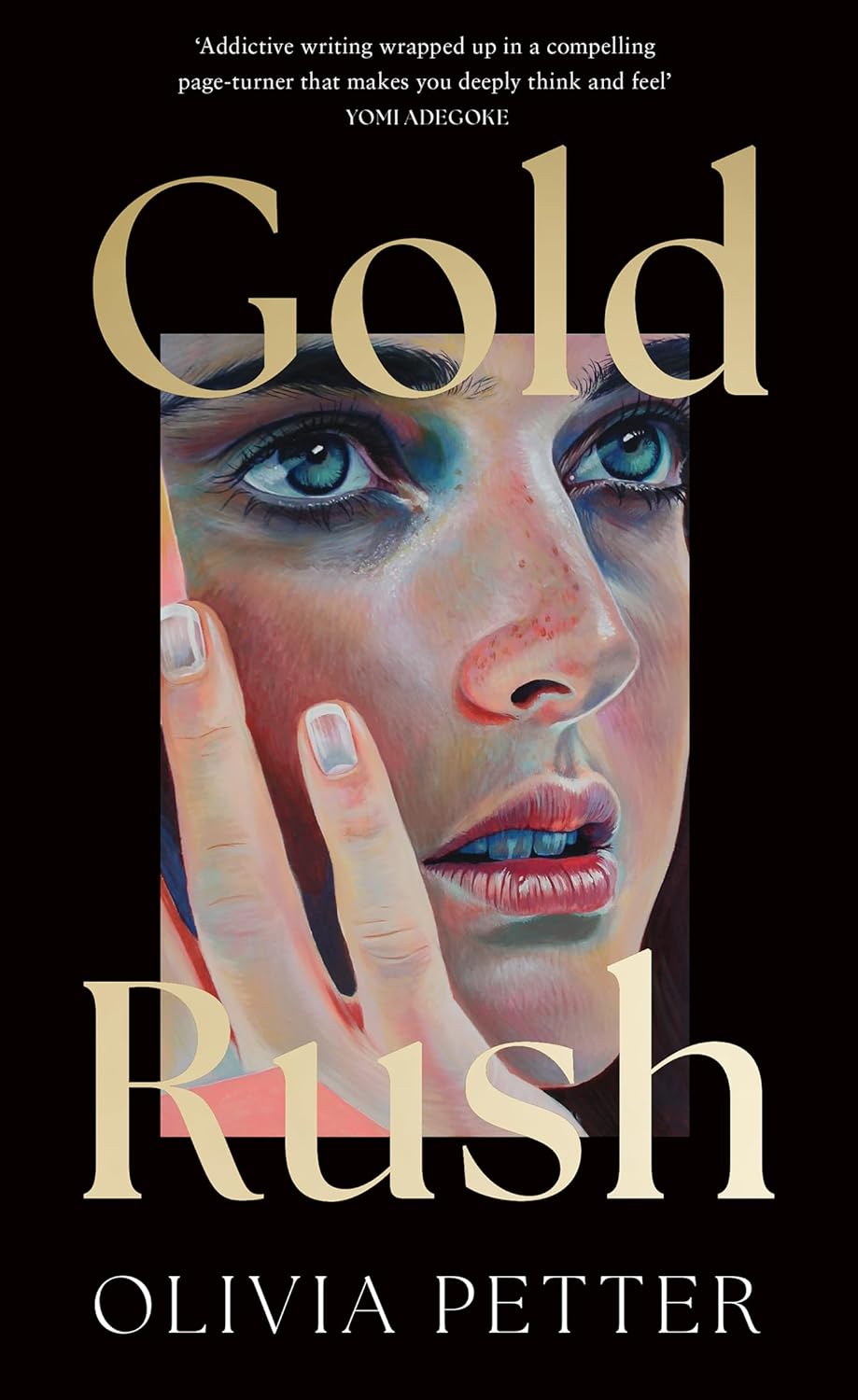

As Olivia Petter publishes ‘Gold Rush’, she explains why she won’t be applying literature’s most annoying trope to her work, even if others might try to

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

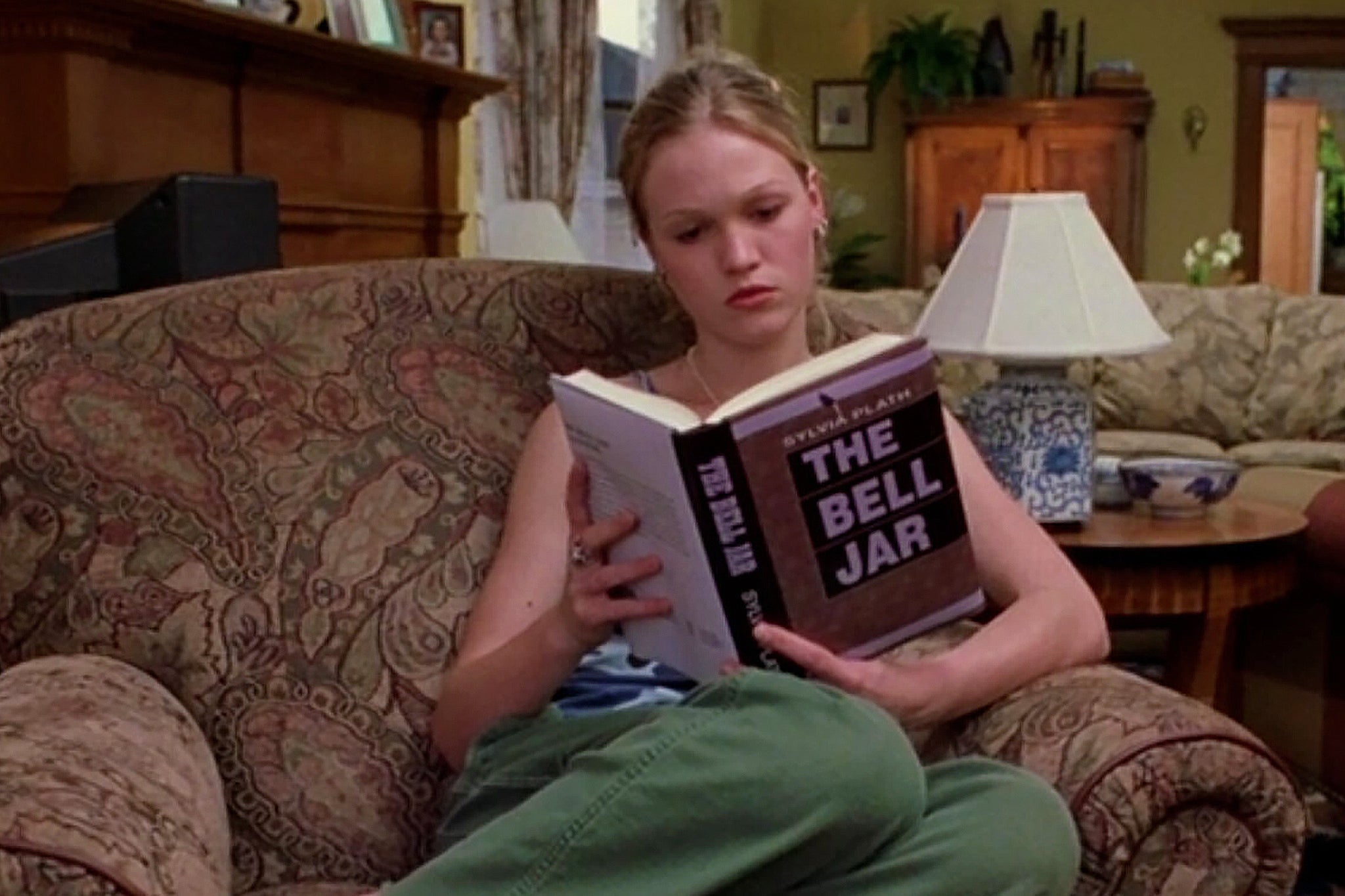

Your support makes all the difference.Think of any “sad girl” in a film. You know the one: she wears baggy jeans and band T-shirts, slams doors and sits alone in canteens. And she’s almost always reading The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath, a semi-autobiographical text that has become the ultimate signifier that a female character is either troubled, tragic or tormented.

There’s 10 Things I Hate About You, in which Julia Stiles’ sardonic character, Kat, pores over Plath’s pages, and cult Eighties comedy, Heathers, when Heather Chandler is found dead with a copy beside her. It’s even referenced in Family Guy and The Simpsons, with Lisa Simpson reading it. And it’s in Netflix’s Sex Education, courtesy of the moody Maeve Wiley.

Fast forward to today and we now officially have the so-called “sad girl” literary trend, which circulates a Bell Jar-shaped fulcrum. In the aftermath of #MeToo, the publishing world has fixated on books in which young women tackle some sort of trauma, usually with covers featuring them faceplanting walls or cakes. These include Cleopatra and Frankenstein by Coco Mellors, which explores alcoholism, loneliness, and sex work, Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason, which is about mental health, Boy Parts by Eliza Clark – a young girl takes pornographic photos of men – and everything by Sally Rooney. Hardly a one-size-fits-all template. And yet, last summer, there was even a book published called Sad Girl Novel by Pip Finkemeyer.

On TikTok, the “sad girl” has become an entire genre in and of itself. One quick search of the term will reveal more than 47 million results. Often, these are short videos showcasing the books with some sort of lingering orchestral music and a marginally creepy voiceover telling you about the meaning of life and love and everything in between. As for what actually defines these titles – if you’re going off TikTok, that is – it could be anything from featuring a female protagonist with a mental illness to one who goes through a bad breakup. The term itself is contested; nobody in the literary world can quite decide if it’s a good or bad label, with some saying it’s patronising or potentially even rather dangerous.

“I don’t want anyone overdosing on Ambien because they read my book,” said Ottessa Moshfegh, a stalwart of the genre. “This is satire, this is not real”. Others, like Finkemeyer, have embraced the genre’s popularity, telling The Guardian: “I’m trying to balance the meta-ness and the tongue-in-cheek references with me wanting to give readers a serious, real part of myself with real emotional depth.”

But what does homogenising so many complex storylines from women say about the female experience? That anything too complicated or too nuanced is beyond our intellectual capabilities? That the gamut of female emotion is simply too vast for mainstream culture? Or does it say something more insidious about how women are judged and oppressed for being their authentic selves? God forbid we ever show rage, passion, or fear; it’s much easier to just be “sad”. I was aware of all this when I started writing my own novel, Gold Rush, which was a process that began as this trend was taking off all around me. Told from the perspective of the twentysomething Rose, the book looks at how a chance meeting with a charismatic, male pop star turns into something more sinister.

I can only hope that readers will see my book as more than “just another sad girl novel”. Because yes, there are “sad” elements to it, but there also lighter parts that satirise the absurdities of fame and the egos that come with it

The majority of the book focuses on the fallout from one drunken night, examining power dynamics between men and women, as well as the nuances surrounding consent and celebrity culture. It’s a complex, deeply personal story. And I was nervous about having something I care so deeply about being taken from me and reduced to a singular catch-all term. Don’t get me wrong, I love all of the authors I’ve mentioned and it would be a privilege to have my work discussed alongside theirs. But if someone were to call my book a “sad girl” novel, I’d feel more conflicted. And not just because of the simplification aspect. First off, there’s the basic sexism of it all (have you ever heard a “sad boy” book?) which taps into a wider, deeply embedded, narrative I’ve noticed percolating around female novelists.

Secondly, there’s the assumption that creative work by women must be autobiographical, something I’ve already been asked countless times, feeling the sting of my imagination being undermined each time. and one that undermines our imagination. Then there’s the infantilisation; girl, not woman. Of course, this is an increasingly absurd conceit that’s endemic across the internet: hot girl summer, tomato girl summer, feral girl summer, hot girl walks, girl dinners, girl math… The tyranny of it all is becoming exhausting. But it feels particularly insidious in a literary context, because it’s once again a way to squash our imaginative authority and to belittle our credibility, both as artists and adults.

Finally, there’s the word “sad”; it seems pejorative. “Your sad little book” and so on. Why not “tragic”? Or “melancholic”? Or literally any other legitimate adjective people use to describe a story, ideally one that hasn’t been snatched from the lexicon of a four-year-old? Why do people have such a hard time taking female novelists seriously? It’s something all of us come up against, too, regardless of the success we’ve achieved; even Rooney, the most successful novelist of her generation, has spoken about how uncomfortable she feels with readers aligning her own life with her books, in which female protagonists are often pensive, esoteric loners.

I can only hope that readers will see Gold Rush as more than “just another sad girl novel”. Because yes, there are “sad” elements to it, but there also lighter parts that satirise the absurdities of fame and the egos that come with it. It examines the modern media landscape, classism and nepotism. It also examines the nuances of sexual trauma and emotional abuse, subjects that I feel aren’t covered nearly enough in pop culture and surely warrant more of a descriptor than “sad”. Like all the titles I’ve mentioned, Gold Rush is fundamentally a book about the female experience. And rather than trying to tie it and others in neat, little bows because that happens to be more Instagrammable, perhaps it’s best just to read these books and categorise them ourselves, with or without a hashtag.