The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

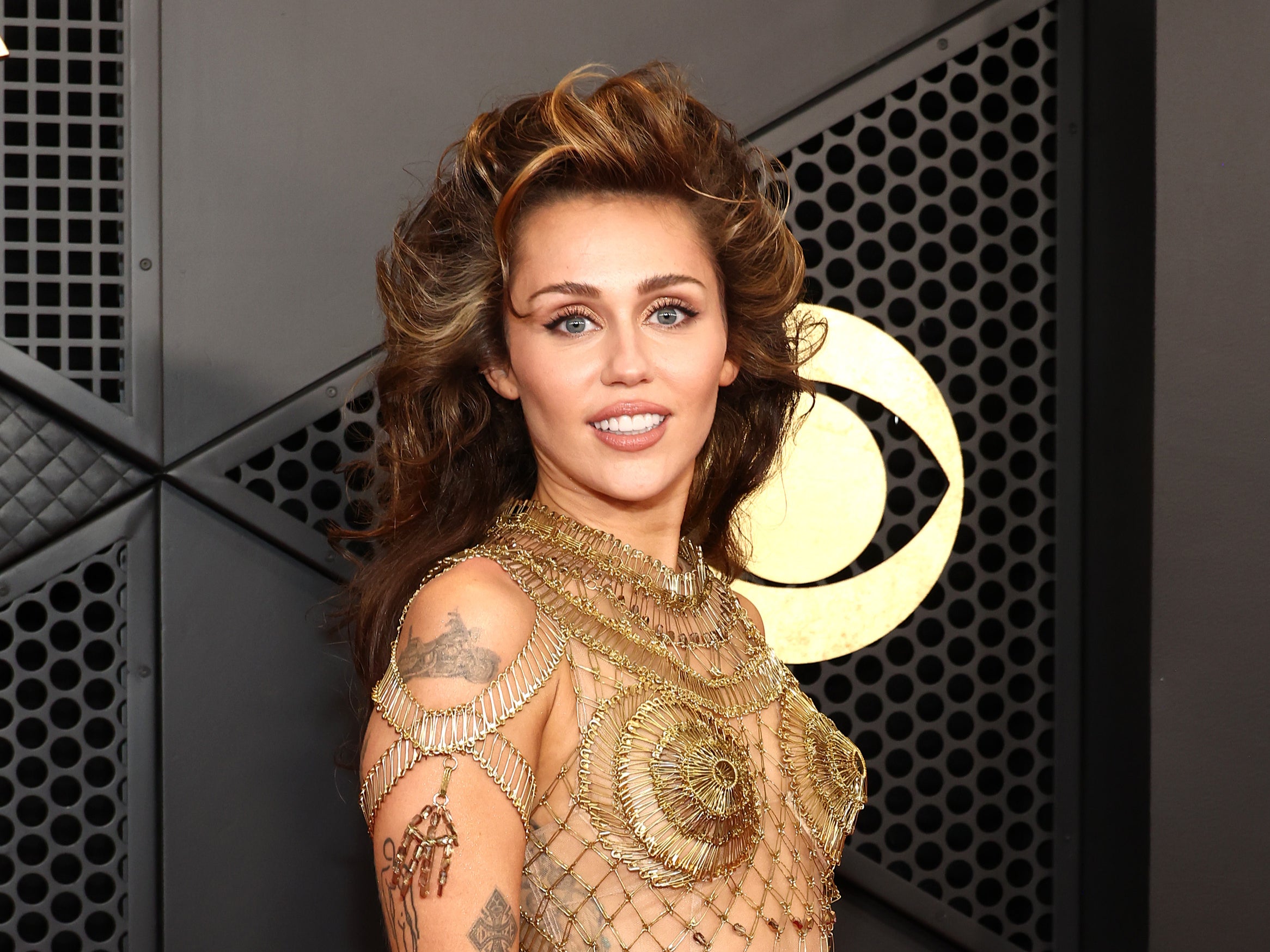

Miley Cyrus is a self-confessed narcissist – could you be one too?

In a world of selfies and social media, it can be tempting to armchair-diagnose everyone with narcissistic traits. Helen Coffey asks the experts what to look for, whether narcissism is always negative, and if it’s possible for people to change

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I inherited the narcissism from my father,” Miley Cyrus said in a recent interview.

The singer was telling David Letterman about her childhood during an episode of the Netflix interview series My Next Guest Needs No Introduction, describing how she and her five siblings had moved from Tennessee to Los Angeles to facilitate her career in show business. Siblings the Hannah Montana star didn’t “know anything about” or even think about at the time, she said. “I was moving to LA, and that’s all I really knew,” she added.

Her admission prompted much speculation: is narcissism really something you can inherit genetically, like being able to roll your tongue or having red hair? And is it even possible for someone to be a narcissist if they’re self-aware enough to start considering that they may be one in the first place?

The word “narcissist” is bandied about with increasing regularity these days, casually levelled at an entire generation of selfie-taking social media addicts as well as being the topic of innumerable TikTok videos telling you the signs to watch out for. But beware of making sweeping armchair diagnoses. The first thing to remember is that narcissism is a spectrum. There’s a difference between someone who is narcissistic, or displays some narcissistic traits, and someone who has narcissistic personality disorder, or NPD, a mental health condition recognised by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).

Helen Villiers is a psychotherapist and, along with Katie McKenna, co-author of the recent bestseller You’re Not the Problem: The Impact of Narcissism and Emotional Abuse and How to Heal. She highlights five main traits she would expect to see in individuals with NPD. “They are: grandiosity, entitlement, exploitation, impaired or motivational empathy and impaired self-awareness.” The first is a feeling of specialness compared to everyone else; the second refers to feeling like you deserve to get anything you want; the third is about using people to get what you want; the fourth involves a lack of empathy or emotional manipulation, using someone else’s empathy against them; and the last is a tendency to blame external factors and other people for problems, never taking responsibility for your own failings.

We all have these traits to some degree – and what’s interesting is that they aren’t all inherently unhealthy if kept in check. In fact, some narcissistic traits, in moderation, can be positive and even integral to living a rich, full life.

“There’s healthy entitlement, when it doesn’t come at a cost to other people,” explains McKenna. “For example, if there’s a promotion at work and someone feels a healthy entitlement to go for it, because they’ve worked hard enough to get it. The difference with unhealthy entitlement is that the person won’t care what they have to do, or who they have to exploit, to get it – and won’t care if they’re qualified or not.”

Grandiosity can also be healthy, giving you a sense of self-worth and self-esteem. “A healthy example is being able to sit here and talk with confidence on a subject we have expertise in,” says Villiers. “But someone with an unhealthy sense of grandiosity would read a Wikipedia page and say they’re an expert. These traits can show up as healthy or unhealthy. And, when they’re unhealthy, they can be extremely toxic to the people around you.”

Dr Craig Malkin, a leading clinical psychologist, Harvard Medical School lecturer and the author of Rethinking Narcissism, draws a clear line between healthy and unhealthy narcissism. “When I looked at all the research, it became clear that the core of narcissism is something called self-enhancement. And self-enhancement is the drive to feel special, exceptional or unique. It’s not self-esteem. It’s not self-confidence. It’s a slightly overly positive view of self.”

While this can obviously be unhealthy when taken to extremes, “the vast majority of happy, healthy people around the world self-enhance. They don’t view themselves as average,” says Malkin. “They see themselves as special, slightly above average – and that, in and of itself, is not a problem.” Furthermore, moderate self-enhancement is associated with positive outcomes. “When people moderately self-enhance, they’re able to give and receive in relationships,” he adds. “They persist in the face of failure, and might even live longer, according to some research studies on health outcomes correlated with self-enhancement.”

In fact, if narcissism is a spectrum, then those at the opposite end from people with NPD – those who don’t self-enhance at all – tend to “suffer”, according to Malkin, with increased anxiety and depression. “They suffer from what’s called the ‘sadder but wiser’ effect. They might have a more realistic or slightly dampened sense of self, but they struggle; and, interestingly, they tend to fall into relationships with extremely narcissistic friends and partners who are more than happy to take up all the space that people who don’t self-enhance are willing to cede.”

Grandiosity can also be healthy, giving you a sense of self-worth and self-esteem

Self-enhancement only becomes a problem, he argues, when it’s addictive and rigid, and when people use it “as a kind of self-soothing – when, instead of turning to people and relationships for care, connection and mutual emotional involvement, they rely entirely on a sense of value and feeling good about themselves by self-enhancing”.

Clearly, when this happens and narcissism tips into something problematic – when it reaches the extreme levels where someone is diagnosable as having NPD – it can hugely hurt others, and often results in unhealthy and even abusive relationships.

Within NPD, there are different types of narcissist, whose behaviours are distinctive; it might not always present in the ways we imagine. There is the classic caricature, called the “overt” or “extrovert” narcissist: the person who wants to feel like they’re the cleverest, richest, most talented, important or attractive person in the room; the person who chases wealth, status and power at all costs (here’s looking at you, Mr Trump). But then there’s the “covert” or “introverted” narcissist, whose drive to feel special ploughs negative furrows instead. They feel like their pain marks them out, that they’re more sensitive than others, that no one understands them. And the “communal” narcissist is different again, describing those who feel special by virtue of their helpfulness or altruism – the person who believes that no one does as many good deeds as them.

The question of whether nature or nurture creates a narcissist is still up for debate. “With all personality disorders, it seems to be a combination,” says psychotherapist Nicholas Rose. “Regarding NPD, if someone had a struggle in life, maybe they had an early childhood struggle, or found it hard to get attention, or conversely received an awful lot of attention, that would have affected how they felt. Chemicals are released in the body; habits can form.” He stresses that, while it’s often “seductive” to look for a specific childhood trauma to pin the blame on, in reality “it’s usually a lot more complex”.

“With personality disorders, it usually means there have been ways of being for a long time, involving a complex interplay between our experiences and who we are,” he adds. “It takes time, compassion and curiosity to work through.”

A genetic predisposition can be negated by a parenting style called “authoritative parenting”, according to Malkin, which is “warm and structuring and tends to foster what we call ‘attachment security’.” Without this attachment, natural narcissistic traits can be exacerbated.

But is a narcissist ever able to recognise that they’re a narcissist? Absolutely, says McKenna, though it will manifest differently depending on what kind of narcissist they are. “There’s a huge misconception that if someone questions whether they’re a narcissist, then they can’t possibly be one – that’s not true,” she says. The overt narcissist might proudly admit to this label, saying “Sure I am, and it’s got me to where I am today.” The covert, conversely, may tend to “weaponise someone’s empathy against them”, McKenna says – asking “How could you say that to me?” if they’re accused of narcissism by a loved one, attempting to make the accuser feel guilty rather than genuinely reflecting or accepting accountability.

Often, narcissism has developed as a defence mechanism – one that’s so strong, it’s tricky to break through. As a result, a low proportion of narcissists end up engaging in talking therapy, the treatment recommended by the NHS for NPD, though covert narcissists are far more likely than overt narcissists to go down this route. “You can think of [overt narcissists] as oblivious narcissists, because they don’t have much self-awareness or capacity to reflect; their defences are really pretty rigid in the extreme, and they’re far less likely to say they have a problem and come into psychotherapy,” says Malkin.

It means the people who end up seeking help are often not the narcissists themselves but their partners or family members. A lot of the discourse and resources online also revolve around those who are in some kind of relationship with a narcissist – how to tell if a partner has NPD, for example. And of course, the welfare of potential victims of emotional abuse needs to be prioritised. But the conversation doesn’t always leave much room for empathy when it comes to narcissists themselves.

Narcissism isn’t inherently abusive, but abuse is inherently narcissistic

“One thing that’s often overlooked is that their lives can be very painful,” Rose says thoughtfully. “Although, in one way, narcissists are seen as very strong and resilient, on the other hand there is a lot of loneliness, frustration and confusion – a lot of questioning about ‘Why is my life like this?’”

He explains: “The way I think about it is this: is being a bully ever good for the bully? I can’t see it. I always see different behaviours as a manifestation of underlying pain, a discord of some sort. The way to engage hurt and pain is not through direct assault but through compassion and curiosity.”

It’s not to say that people in psychologically damaging or emotionally abusive relationships shouldn’t remove themselves from the situation; more that labelling, and jumping to write people off, can be problematic in its own way. “If you’re in an abusive relationship, the abuse needs to end first,” says Malkin firmly. “It doesn’t matter what’s causing it. Don’t diagnose your friend or partner. Ask yourself if you’re safe emotionally and physically, and if the answer is no, it doesn’t matter what their diagnosis is, you need help ending that relationship and distancing from the person until they overcome their tendency to abuse.”

He’s also uneasy with the common conflation of narcissism and abuse. “Narcissism isn’t inherently abusive,” he argues. “But abuse is inherently narcissistic. As soon as you’re abusive, you’re forgetting about the needs and feelings of someone else; you’re acting as though you’re so special that you should be able to do anything you want.”

While not everybody believes that narcissism or NPD can be “cured” as such – and none of the experts I’ve spoken to would ever recommend hanging around in a toxic dynamic in the vain hope that someone might one day change – Malkin certainly believes that positive outcomes are possible for those who engage authentically with the therapeutic process. “I see a number of people with narcissistic personality disorder,” he says. “There’s hope for people who come in for genuine treatment and stick with it.”

As for Cyrus, the Grammy winner may well just have been a regular teen all along, whatever she might have told Letterman. “She was a young teenager when the family moved to LA, and developmentally, teenagers don’t tend to consider people outside their own experience. We don’t expect to see that,” says Villiers. So go easy on yourself, Miley – and maybe leave the diagnoses to the professionals.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments