The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Meet the students studying for an MA in The Beatles

Is studying an MA in The Beatles really worth your while? Alex Marshall finds out

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On Wednesday morning, as a new semester begins, students eagerly head into the University of Liverpool’s lecture theatres to begin courses in archaeology, languages and international relations.

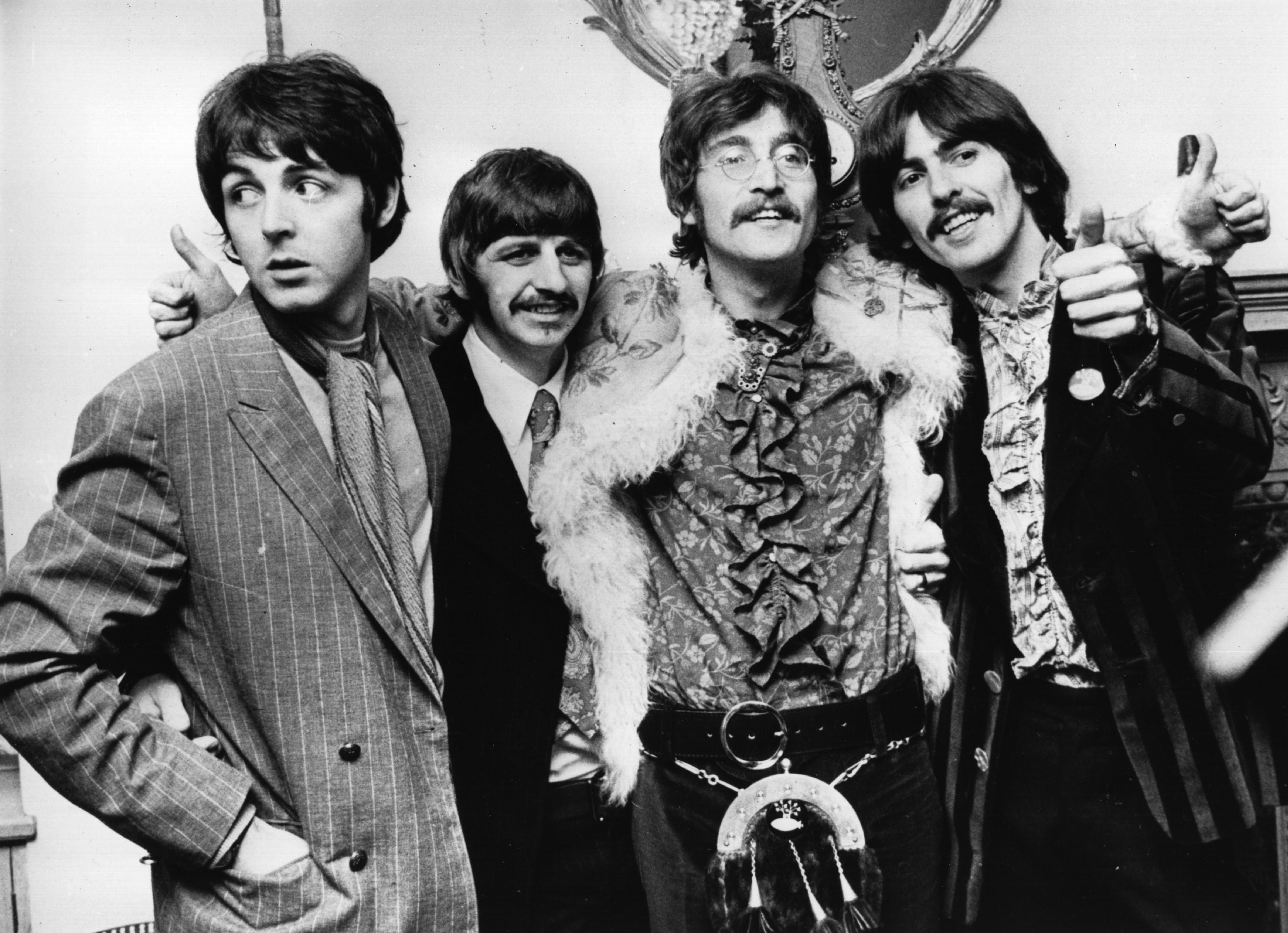

But in lecture room No 5 of the university’s concrete Rendall Building, a less traditional programme is getting underway: a master’s degree devoted entirely to The Beatles.

“How does one start a Beatles MA?” asks Holly Tessler, the American academic who founded the course, looking out at 11 eager students. One wears a Yoko Ono T-shirt; another has a yellow submarine tattooed on his arm.

“I thought the only way to do it, really, is with some music,” she says.

Tessler then plays the class the music video for “Penny Lane,” the band’s tribute to a real street in Liverpool, just a short drive from the classroom.

The year-long course – The Beatles: Music Industry and Heritage – will focus on shifting perceptions of The Beatles over the past 50 years and on how the band’s changing stories affected commercial sectors like the record business and tourism, Tessler says in an interview before class.

For Liverpool, the band’s hometown, the association with The Beatles was worth more than £80m a year, according to a 2014 study by Mike Jones, another lecturer on the course. Tourists make pilgrimages to city sites named in the band’s songs, visit venues where the group played – like The Cavern Club – and pose for photos with Beatles statues. The band’s impact was always economic and social as much as musical, Tessler says

A postgraduate qualification in The Beatles is a rarity, but the band has been studied in other contexts for decades

Throughout the course, students will have to stop being simply Beatles fans and start thinking about the group from new perspectives, she adds. “Nobody wants or needs a degree where people are sitting around listening to Rubber Soul, debating lyrics,” she says. “That’s what you do in the pub.”

In Wednesday’s lecture, which focuses almost entirely on “Penny Lane”, Tessler encourages students to think of The Beatles as a “cultural brand”, using the terms “narrative theory” and “transmediality”.

Then she applies those ideas to a recent Beatles-related event. Last year, Tessler said, street signs along the real Penny Lane were defaced as Black Lives Matter protests spread across Britain. There was a long-standing belief in Liverpool, she explained, that the street was named after an 18th-century slave trader, James Penny. (The city’s International Slavery Museum listed Penny Lane in an interactive display of street names linked to slavery in 2007, but it now says there is no evidence that the road was named after the merchant.)

“What would happen if they did change the name to – I don’t know – Smith Lane?” Tessler asks. That would deprive Liverpool of a key tourist attraction, she says: “You can’t pose next to a sign that used to be Penny Lane.” The furore around the street name showed how stories about The Beatles can intersect with contemporary debates and have an economic impact, she says.

The course’s 11 students – three women and eight men, aged 21 to 67 – all say they are long-term Beatles obsessives. (Two named their sons Jude, after one of the band’s most famous songs; another has a son called George, after George Harrison.)

Dale Roberts, 31, and Damion Ewing, 51, are both professional tour guides and hope the qualification will help them attract customers. “The tour industry in Liverpool is fierce,” Roberts says.

Alexandra Mason, 21, says she has recently completed a law degree but decided to change track when she heard about the Beatles course. “I never really wanted to be a lawyer,” she says. “I always wanted to do something more colourful and creative.”

She adds, “In my mind, I’ve gone from the ridiculous to the sublime,” but admits that some might think she’s done the opposite.

A postgraduate qualification in The Beatles is a rarity, but the band has been studied in other contexts for decades. Stephen Bayley, an architecture critic, who is now an honorary professor at the University of Liverpool, says that when he was a student in the 1960s at Quarry Bank High School in Liverpool – John Lennon’s alma mater – his English teacher taught Beatles lyrics alongside the poetry of John Keats.

In 1967, Bayley wrote to Lennon asking for help analysing songs on Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Bayley said Lennon “wrote back basically saying, ‘You can’t analyse them.’”

But these days a growing number of academics are doing just that. Tessler says researchers in several disciplines are writing about The Beatles, many exploring perspectives on the band informed by race or feminism. Next year, she plans to start a journal of Beatles studies, she says.

Some people in Liverpool, however, are not convinced about the band’s academic value. In interviews around Penny Lane, two locals say they think the course is an odd idea.

“What are you going to do with that? You’re not going to cure cancer, are you?” says Adele Allan, owner of the Penny Lane Barber Shop.

“It’s an entirely silly course,” says Chris Anderson, 38, out walking his dog, before adding that he thinks almost all college degrees are “entirely silly.”

Others are more positive. “You can study anything,” says Aoife Corry, 19. “You don’t need to prove yourself by doing some serious subject.”

Tessler concludes Wednesday’s class by outlining the subjects for the semester’s remaining lectures. It is a programme that any Beatles fan would savour, including field trips to St Peter’s Church, where Lennon and McCartney first met in 1957 in the church hall, and Strawberry Field, the former children’s home the band immortalised in song. Classes will cover key moments in the band’s history, including a famous live television appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show and Lennon’s murder in 1980, Tessler says.

She then gives students a reading list, topped by a textbook called The Beatles in Context. “Are there any questions?” she asks.

“What’s your favourite Beatles album?” calls out Dom Abba, 27, the student with the yellow submarine tattoo.

Tessler gamely answers (“The American version of Rubber Soul”), then clarifies what she means: “Does anybody have any questions about the module?”

The students clearly still have some way to go before they become Beatles academics as much as fans. But there are still 11 months of lectures left.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments