Masculinity has evolved far beyond The Beatles and James Bond – and that’s a good thing

As a new book explores the contrasting impact 007 and The Beatles had on British men, Louis Chilton asks whether we can ever – or should ever – define what makes a man

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Don’t ask me to explain masculinity to you. How on earth does anyone define a loaded, nebulous concept like that in the year 2022? It can’t be done. As society – or progressive society, at least – comes to re-evaluate and, ultimately, reject the preconceptions of the traditional gender binary, how do we discern what behaviours or qualities are “masculine” at all? Often, something is said to be masculine simply because a man is doing it – whether that’s skinning elk, sporting facial hair or watching Entourage. But the idea that any action is inherently, immutably “male” is nonsense.

As Sky Sports viewers saw two weeks ago, the boundaries of what is considered gendered activity can be rapidly redrawn. Ex-Liverpool midfielder and current football pundit Graeme Souness invoked a flurry of internet outrage when he referred to football being a “man’s game again” (just “men at it”, he enthused, after a prickly match between Chelsea and Spurs). Sat next to former England Women’s international Karen Carney, Souness seemed to have scored a sloppy own goal. They’ve let grandad on the airwaves again, fumed a nation still hot from the thrill of a historic Women’s Euros victory. And yet, even five years ago Souness’s remarks wouldn’t have caused anyone to bat an eyelid.

Our collective understanding of masculinity is inextricably tied into our popular culture – not just sport, of course, but TV, music, film, fashion. It’s something that’s explored in John Higgs’s forthcoming book, Love and Let Die: Bond, The Beatles and the British Psyche. The book homes in on two cultural behemoths – James Bond and The Beatles – and explores their different impacts on the public consciousness. But while Ian Fleming’s philandering superspy and the four Scouse pop musicians might represent wildly different masculine ideals, there’s something fundamentally fruitless in searching for hard truths about gender among pop culture’s idols.

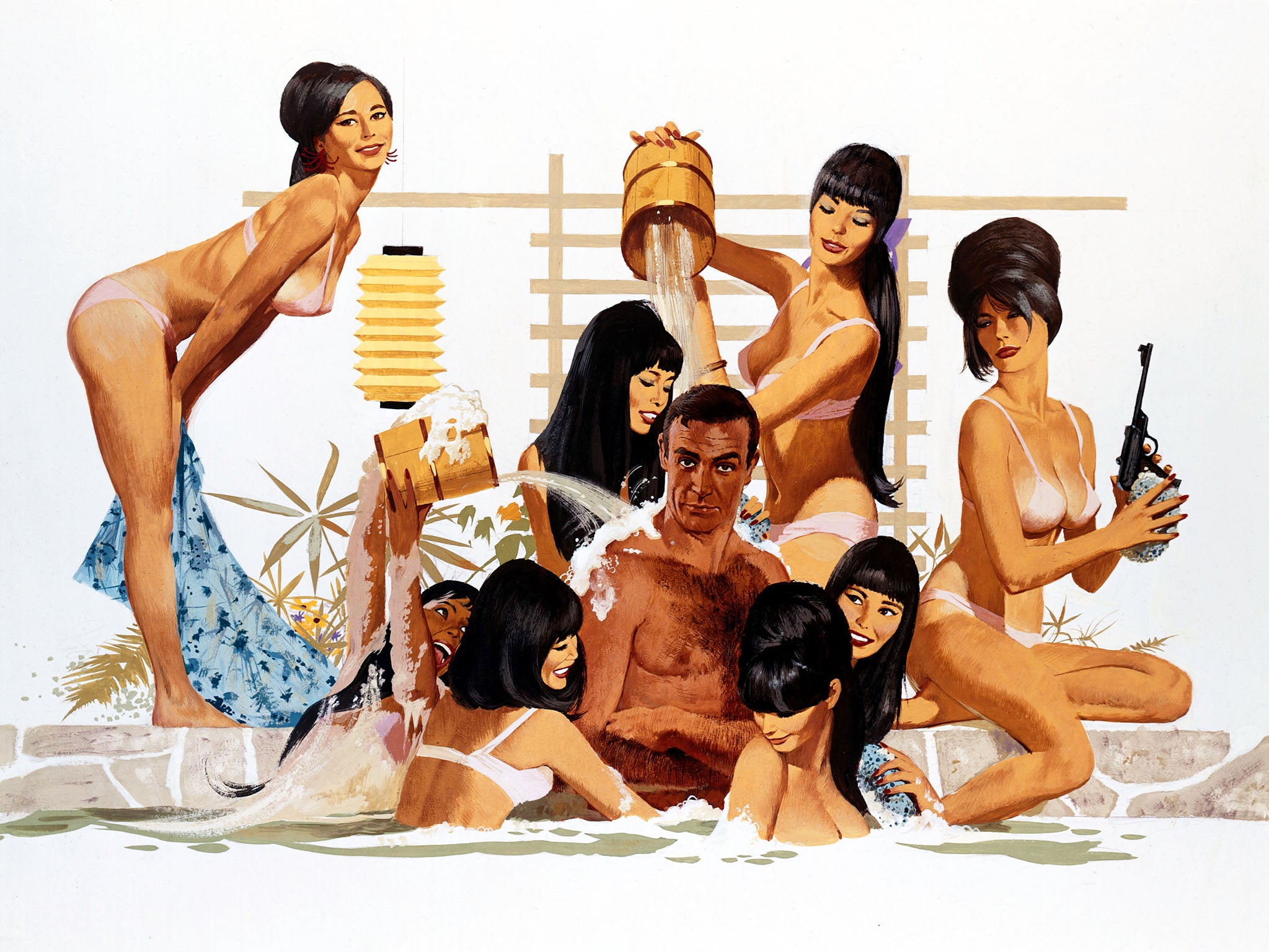

For many men, particularly older men, Bond embodies the ideal of traditionalist masculinity. He’s physically dominant, sexually promiscuous, materially wealthy, and completely closed off to his emotions. “When Bond was born, he personified an aspect of the male identity that was prevalent after the war – that of the protector,” writes Higgs. “[That role] is now less necessary.” Bond can inspire obsession in a certain kind of man – a fanaticism satirised expertly in Steve Coogan’s Alan Partridge (himself a pop culture creation who reflects, rather than dictates, British masculine mores).

For others, though, and especially younger people, Bond embodies everything that’s toxic and wrongheaded about “conventional masculinity”. He’s violent. Sexist. Callous. A rapist, by any modern definition. Even overlooking the queasy imperial undertones to his jetsetting spyscapades, there’s something about him that feels at odds with any even halfway palatable vision of a 21st century man. The recent Daniel Craig Bond films have tried to wrestle with this: Craig’s 007 is painted as a man out of time, an emotionally repressed dinosaur who has the more sexually and racially diverse younger generation nipping at his heels. But we are nonetheless supposed to root for him; in the climax it is always Bond who saves the day. The ends unfailingly justify his dusty old means.

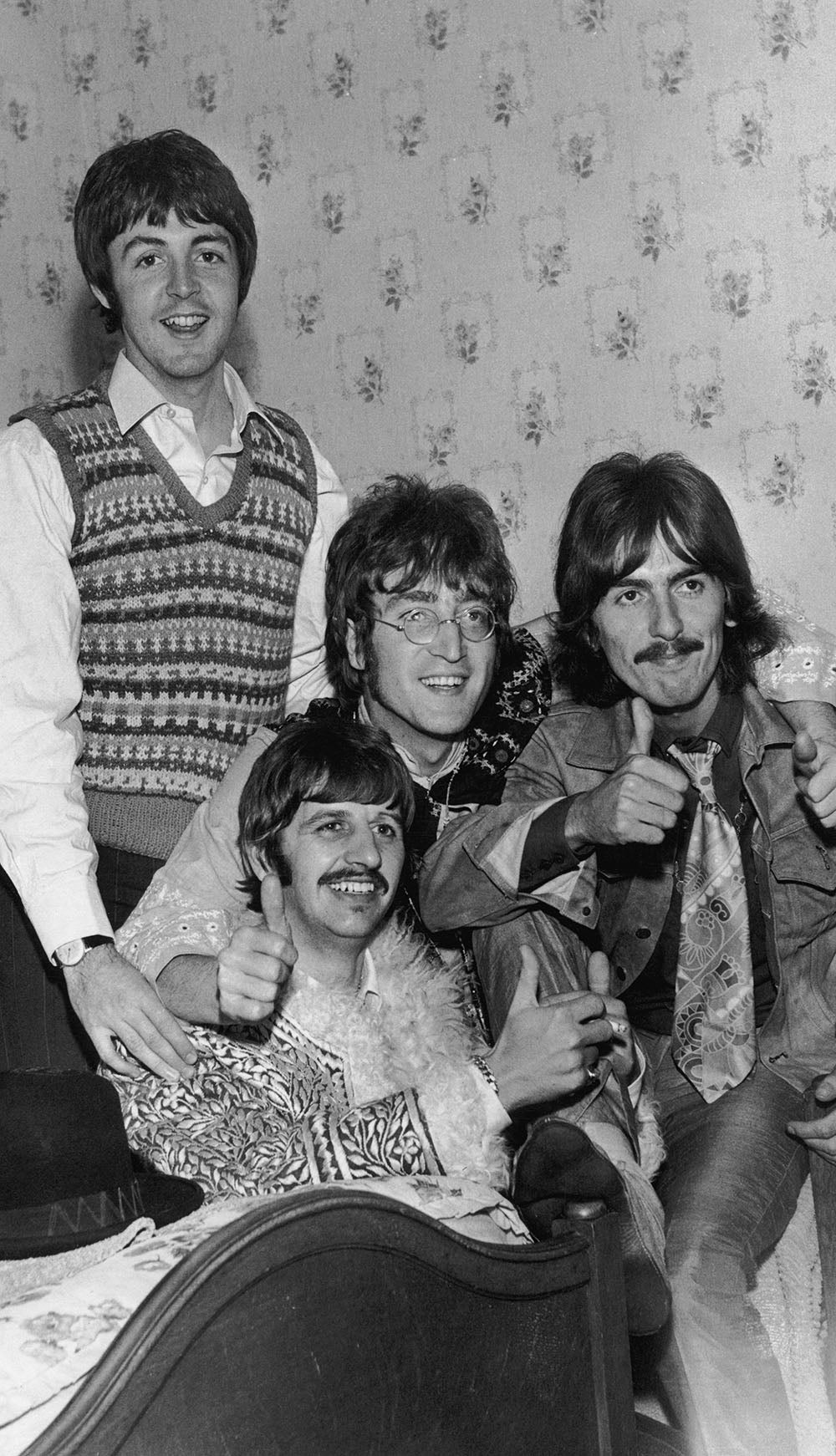

The Beatles, on the other hand, existed at the other end of the spectrum. Much has been written about how the iconic rock band subverted gender norms. They had long hair; they were physically unimposing – effectively more boys than men when they first rose to prominence. Martin King, author of 2013’s Men, Masculinity and The Beatles, has written about the significance of the band’s 1965 film Help!, claiming that the masculinity embodied in the film is “a key stepping stone to more obvious displays of gender fluidity that were to emerge in later decades”.

It’s easy to look at a contemporary pop star such as Harry Styles – someone who has drawn considerable praise for his willingness to subvert gender norms in his fashion choices – as a modern-day successor. What made The Beatles unique, of course, was that they were able to serve as a radical transformative social presence while also revolutionising pop music itself. Their brand of masculinity was legitimised both by the genius of their music and the cultural pervasiveness that resulted. With all due respect to “Watermelon Sugar”, I don’t think Styles can lay a similar claim to this.

Last year’s musical docuseries Get Back, filmed when The Beatles were recording Let It Be in early 1969, was illuminating when it came to how The Beatles functioned as a group of four men. You could see it in the way Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr behaved – compassionately, warmly, jovially – around Linda McCartney’s young daughter, Heather (soon to be adopted by Paul). You could see it in the way John Lennon kept Yoko Ono, who had suffered a miscarriage just weeks before filming, by his side at nearly all times. You can see it in the general sense of camaraderie between the bandmates, palling around in the specific, easy way that longtime male friends do.

This isn’t to overlook the more complicated realities of their private lives – John Lennon’s admissions of domestic abuse being perhaps the most unsavoury. I’m sure some sceptics would point to the band’s break-up as being a stereotypically masculine clash of egos (though all-female pop groups have proven just as susceptible to bitter separations). For all their ruffling of the feathers of traditional male identity, The Beatles were also a group of four straight, white, cisgender men. They represented far less of a threat to hegemonic notions of conventional masculinity than, say, someone such as Lil Nas X does now (or someone such as James Baldwin did, on a less prominent scale, years before The Beatles ever released a single).

When we look at masculinity in media, it is often through the lens of role models. The question becomes what examples we should be setting for kids – about the kinds of men that we, as a society, are raising. But masculinity isn’t something that simply concerns men. This line of thinking often overlooks how important it is for girls and non-binary kids to also have positive male role models, and for boys to have strong non-male ones. To go back to The Beatles: the majority of their fanbase comprised young women. The intended audience for this new, subversive brand of masculinity was never actually men.

Masculinity isn’t – or shouldn’t be – something that we simply lift wholesale from one aspirational figure. It is something people learn to express gradually, instinctively patchworking our own understanding of it from the entire gamut of human experience. I don’t know really what it means to be a cis man in an era when gender seems a more tenuous and fluid construct than ever. But I know this much: it doesn’t mean James Bond.

‘Love and Let Die: Bond, The Beatles and the British Psyche’ by John Higgs is published on 15 September via W&N in Hardback, eBook and audio

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments