Is there really such a thing as ‘toxic femininity’?

This year’s ‘Love Island’ has been marred by accusations of ‘toxic femininity’, after behaviour from its female contestants left male contestants in tears. Eloise Hendy talks to experts to unpack this new, contentious term

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the eight years since Love Island first crashed onto our screens like a reality TV wrecking ball, it’s become a cliche to describe it as “toxic”. “Toxic relationships”. “Toxic bullying”. Most of all, “toxic masculinity”. In the last fortnight, after some particularly dramatic, tear-soaked scenes, a new term has been added to this illustrious list: “toxic femininity”. But... do we even know what “toxic femininity” really means?

In the past, there have been numerous complaints about “toxic” behaviour from male contestants. Adam Collard calling Rosie Williams “needy”. Jordan Hames cracking on with India Reynolds two days after staging an elaborate girlfriend proposal for Anna Vakili. The actions of every dude inducted into the hall of infamy known as “Destiny’s Chaldish”. This seemed to peak last summer when Luca Bish and Dami Hope were accused of bullying Tasha Ghouri, prompting Women’s Aid to criticise the show for depicting “misogynistic and controlling behaviour”. The annual tradition of Movie Night, in which clips of private antics are broadcast to the show’s entire cast, also sparked an Ofcom storm.

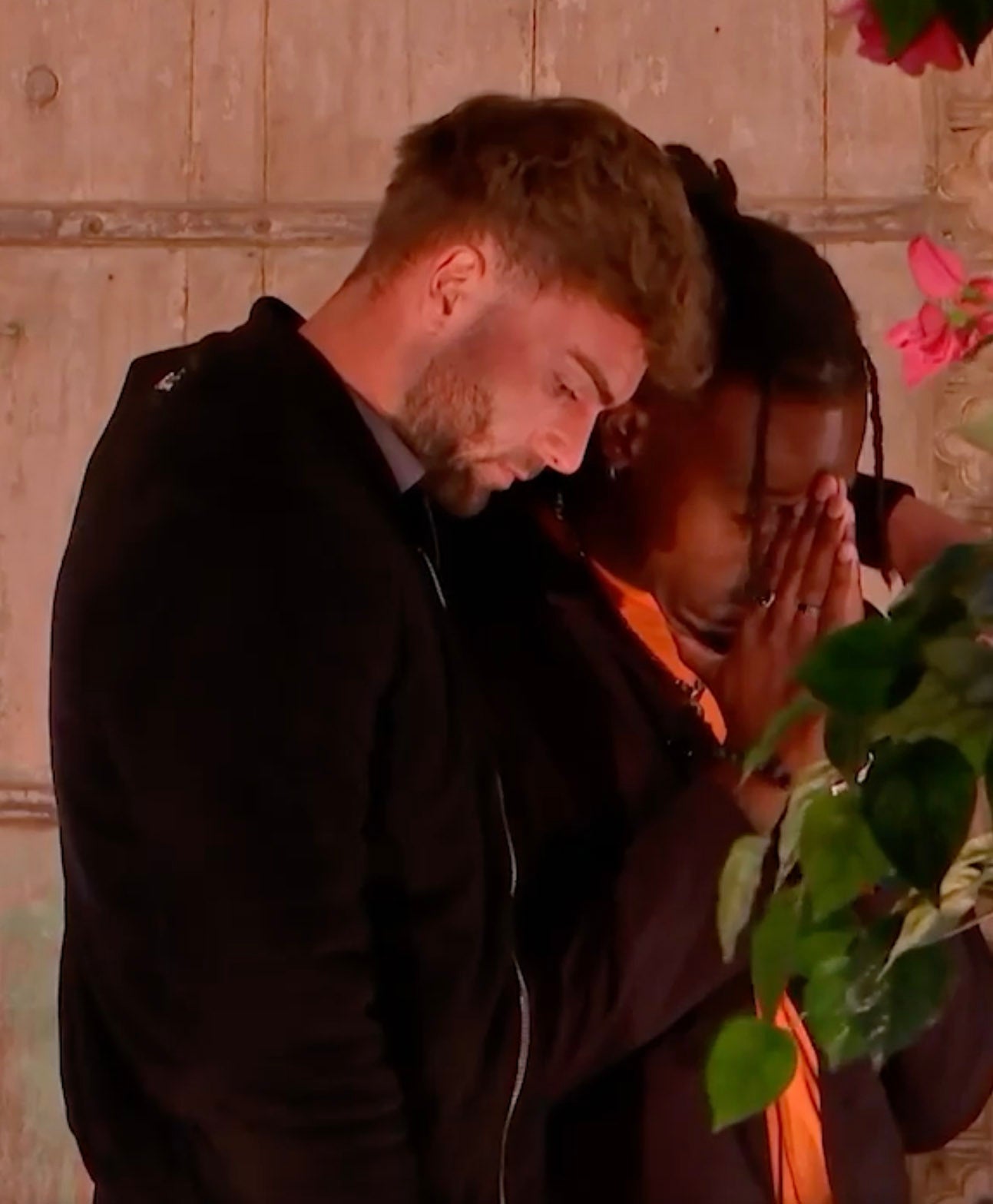

Less than two weeks ago in the current series of Love Island, Movie Night caused another ruckus. This one, though, played out differently to series past. Rather than ending with the fellas smirking and brushing off accusations of foul play, this year it was the girls – specifically Jessie, Olivia and Tanya – who went on the defensive. Both Shaq and Tom were seen breaking down in tears. Viewers have since been questioning whether Love Island producers – wary of replicating the toxic masculinity of earlier seasons – have in fact reset the dial too far, with many fans branding the women’s behaviour “toxic femininity”. This led men’s domestic abuse charity ManKind Initiative to call on producers to ensure male contestants were being offered the same duty of care as female contestants. In a further statement, the charity said: “Love Island has once again showed [sic] that when it comes to abusive behaviours against partners such as manipulation and gaslighting, it affects men as well as women.”

The fact that men can be victims of abuse is, of course, inarguable. But is “toxic femininity” the right label to apply to the kind of behaviour we’ve seen in the villa? The phrase has recently gained traction online – popping up in girlbossy workplace features, therapy advice sites, and YouTube videos about “femcels”. Yet even this cursory glance at its use reveals a vast disparity in what the term is deemed to mean. Is “toxic femininity” about women behaving in a way we have deemed “toxic”, such as gaslighting your partner, or using emotional manipulation to get your way? Is it meant to recognise that women can be bad too – that they are, in fact, just as bad as the boys? Or is it about specifically “feminine” traits? Is “toxic femininity” meant to capture the gendered expectations placed on women in society? Essentially, are discussions about “toxic femininity” fair, feminist, or decidedly anti-feminist?

Mark Brooks, chair of the ManKind Initiative, wants to move away from gendered terms in general. “There is no such thing as toxic femininity – or toxic masculinity, for that matter,” he argues. “There [are] just toxic people and behaviour.” On the surface, this seems like a fair and egalitarian approach. Yet Brooks goes on to state his belief that the term “toxic masculinity” is “very anti-male and victim-blaming”. He says it “demonises a whole gender”. This is a similar line to the one taken by many men’s rights activists over the last few years. They too consider discussions about “toxic masculinity” as an attack on men as a whole, despite the term being intended to highlight how masculinity can be warped by patriarchy, valorising male displays of violence, anger and disaffection. This damages both the men enacting it and the people it impacts.

“Toxic femininity”, meanwhile, has often been used in conjunction with cases where women have spoken out against precisely this kind of violent or abusive male behaviour. Amber Heard, for example, was condemned in these terms when discussing her suffering at the hands of Johnny Depp. She was the perfect example of “toxic femininity”, critics proclaimed, accusing her of “playing the victim”. In this context, it seems dangerous to give any more weight to men’s rights activists’ anti-feminist claims that they are the most discriminated against in society. But is it right to try and move the conversation away from gender, and onto behaviour?

Women are just as capable of promoting toxic masculine standards as men, and ultimately it’s a force that is widespread and cultural

Alicia Denby is a sociologist and PhD student at Manchester Metropolitan University, who specialises in intimacy, gender, modern dating practices and singlehood. Recently, some of her research has looked specifically at Love Island and its portrayal of gender. “There are no intrinsic qualities that make toxic behaviour masculine or male,” she says, “as we’ve seen by emotional abuse and manipulation among female contestants in recent years.” She points to the case of Faye Winter, who was condemned in 2021 for screaming at her partner Teddy – an altercation which prompted over 25,000 complaints to Ofcom. But Denby highlights that the amount of complaints received in Faye’s case was, for example, over 20 times greater than the number submitted about Luca’s bullying of Tasha. In the villa and out of it, women who are angry, mean, or demeaning to others often receive more intense and lasting censure, because anger in itself is seen as an unacceptable feminine trait. “Certainly this is not to say that women should not be held accountable for causing distress towards fellow contestants,” Denby stresses, “but this should not be used as an excuse to fuel an anti-feminist agenda.” Denby instead suggests that “rather than describing behaviours as ‘toxic masculinity’ or ‘toxic femininity’, we should call this what it is, which is emotional abuse.”

Psychologist and psychotherapist Nova Cobban seems to agree. “In reality,” she says, “toxic behaviour is not gender specific or even gender related, it’s all essentially just negative behaviour designed to assert dominance.” Yet while this seems like an ostensibly feminist and progressive line to take, there is a risk of losing sight of the specific ways gender is socially constructed and enforced.

Ali Ross, psychotherapist and spokesperson for the UK Council of Psychotherapy, suggests shifting the focus away from the idea that women can also behave in “toxic” ways; instead, we should explore the inherent toxicity within the expectations of what femininity “should” look like. He sees “toxic femininity” as “an endorsement of patriarchal values”. “Slut shaming is a good example,” he says. “No one wins, as the shamer also has to hold themselves to these standards and close the door on any possibility for them to be sex-positive themselves.”

Similarly, trauma and emotional resilience expert Dr Lisa Turner suggests toxic femininity “can be understood as a set of negative traits or behaviours that reflect the harmful aspects of gender-based stereotypes of women”. Like Ross, she suggests that “toxic femininity can involve shaming and ostracising women who do not conform to these standards or who challenge traditional gender roles”. Rather than toxic behaviour then, the issue becomes one of gender regulation. Yet by this stage, the term “toxic femininity” seems confused – used to both advance and critique gender-based stereotypes.

Hannah McCann, a University of Melbourne lecturer in cultural studies, says that she’s observed in recent responses to Love Island a suggestion that women are “just as bad” as men in terms of domestic and emotional abuse. “There has clearly been an attempt to use ‘toxic femininity’ to claim that men can be victims of women,” McCann argues. “Ultimately these pieces read as a kind of ‘gotcha’ sensationalism – as if to say, ‘feminism has it wrong, women are just as bad as men’.” She believes much of the discourse on the Love Island row has been “trying to misconstrue the fact that women are overwhelmingly the victims of domestic violence at the hands of men, presenting the events on Love Island as ‘evidence’ that the phenomenon is in fact equal.” She thinks arguments of this kind are dangerous: “This is very similar to the kind of rhetoric we see in Men’s Rights Activism.”

This isn’t to suggest McCann thinks men cannot be victims of abuse. She makes it clear that it is “all well and good to examine how men can be victims of abuse, and indeed how women can participate in negative or abusive behaviours”. Yet she believes discussions of this kind could be “a good opportunity to look at the actual data about domestic abuse” and how it manifests. It’s much more productive and fair to instead look at how “certain approaches to gender are toxic, rather than some individual expressions or traits, because this allows us to see the bigger political picture”. In the past, she has spoken about whether anti-trans feminists could be seen as having a “toxic” approach to femininity because of their rigid adherence to a biological gender binary and promotion of the surveillance of women’s bodies.

Promotion of a rigid gender binary cuts to the heart of the whole issue. In a 2018 Medium post titled “toxic femininity holds us all back,” social psychologist and author Dr Devon Price wrote that “our current cultural examination of toxic gender roles is too focused on blaming men and masculinity for a variety of ills that are actually caused by the gender binary and our strict adherence to it”. He suggested that both toxic masculinity and toxic femininity are “cultural diseases” that everyone is infected by.

“These two forces are systemic,” he tells me. “They wound up being learned and internalised by just about anybody who exists in our culture, because we all get bombarded with painful lessons about how to ‘do’ gender correctly, starting when we’re very young.” Dr Price suggests that toxic masculinity in particular is often misunderstood as an insecurity or set of rules individual men have, “but in reality women are just as capable of promoting toxic masculine standards, and ultimately it’s a force that is widespread and cultural”.

In a similar vein, Dr Price argues toxic femininity “refers to the really punishing set of social standards for what it means to be a woman ‘correctly’,” and adds that “it’s easy for any person, regardless of their gender, to pass on these standards, because we are basted in them every moment of every day of our lives”. One of the things doing this cultural basting right now is Love Island’s heterosexual, gender-normative parade. The same punishing set of standards requires the women of Love Island to form cliques and spend hours on their makeup every night, and the men to have a “boys will be boys” attitude. It also helps explain why viewers have such extreme reactions to seeing men like Shaq and Tom being brought to tears – precisely because it is still rarer to see men on the programme displaying emotional pain than grinning through it and cracking on.

Terms like “toxic masculinity” and “toxic femininity” can be misused and misconstrued, flung about to advance a distinctly anti-feminist view of gender relations and systems of power. But we shouldn’t lose sight of the real issue, which is how everybody is kept locked in a toxic gendered system. As Dr Price wrote in 2018, “the problem was never just masculinity. It was, and is, inflexible gender roles for men and women alike.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments