Were they guilty or not guilty?

You can’t ask me that! Continuing her series tackling socially unacceptable questions, Christine Manby asks if it should be up to a general public jury to decide a defendants’ fate

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mention jury service in any conversation and you’ll likely get one of two responses. Either the person you’re talking to will say they’d love to do it but have never been called or they’ll say that they’ve done it and they don’t want to do it again. If the ex-juror did find the process interesting, while they can tell you what happened in the courtroom, they can’t actually discuss the jury deliberations anyway. Even after the trial, disclosing what happened in the jury room could land you in contempt of court. To be called to serve on a jury is no small thing when the answer to the question “guilty or not guilty” has the power to change the course of a stranger’s life.

The early history of the jury is unclear. The system of trial by a group of your peers may have come to the UK with the Vikings, who installed 12 hereditary “law men” in each of the British towns under their control. King Ethelred the Unready provided for a sort of jury service in 997, when he decreed that the 12 eldest “thegns” in each “wapentake” or county, should investigate local crimes. “And let them swear on holy relics, which shall be placed in their hands, that they will never knowingly accuse an innocent man nor conceal a guilty man,” must be the origin of swearing on a holy book or affirming your intention to give the defendant a fair trial.

Certainly, by the time of the Norman invasion, the tradition seems well established. In the 12th century, the criminal fraternity must have breathed a sigh of relief when Henry II favoured the jury method over the still widely used “trial by ordeal” (which, among other things, involved proving your innocence by drowning when dunked in a pond). And in 1215, the right to a trial by jury was enshrined in English Law by the Magna Carta.

Since then, the jury process has had its ups and downs. In 1670, Quakers William Penn and William Mead were arrested for unlawful assembly. When a jury sought to modify the verdict to “guilty of speaking to an assembly in Gracechurch Street”, the judge locked the 12 men up without food or water, telling them they “shall not be dismissed until we have a verdict that the court will accept”. The jury endured a two-day fast before delivering a not guilty verdict, which landed them with a fine for contempt of court. William Penn later founded Pennsylvania.

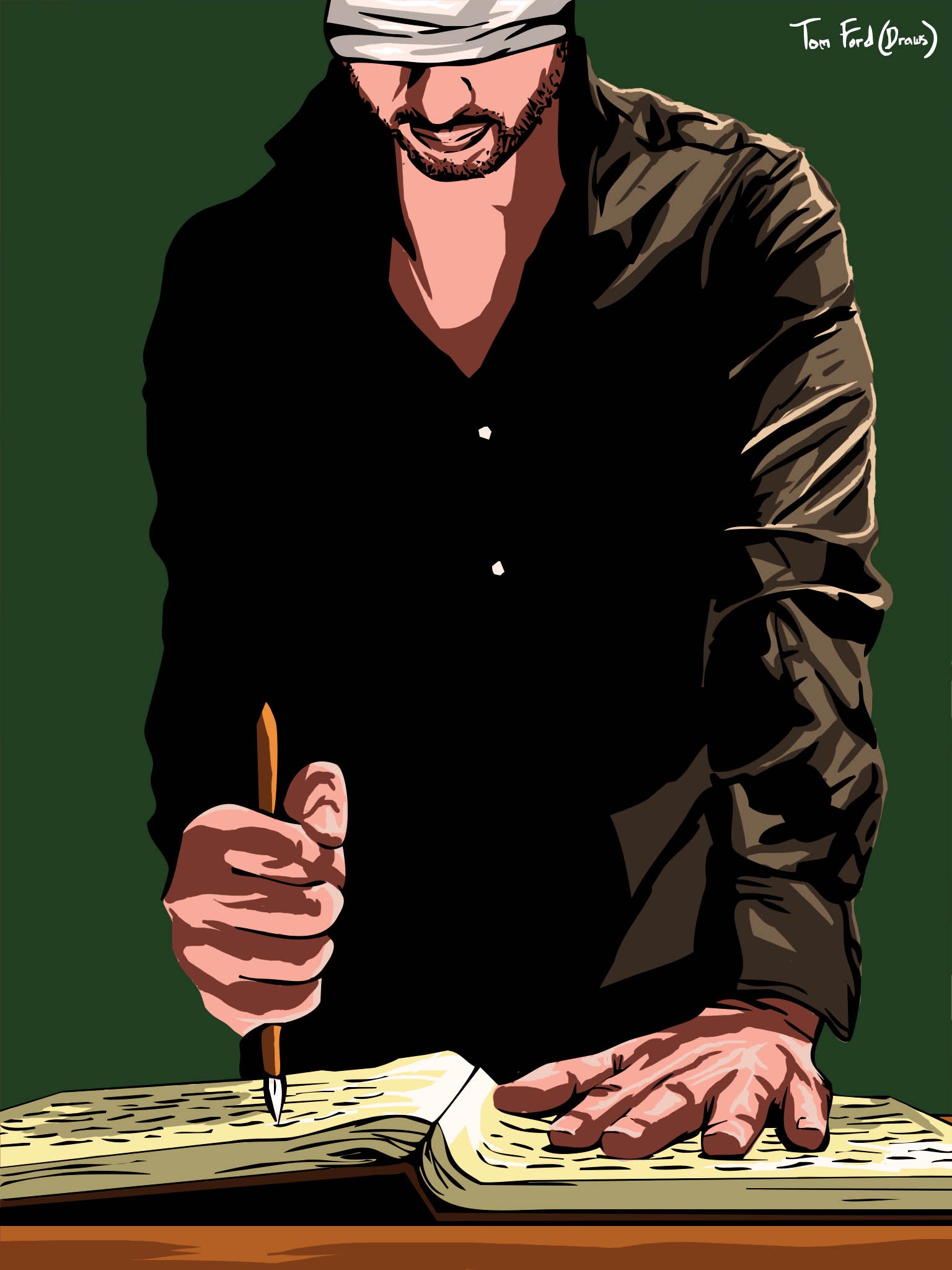

In the 18th century, professional jurors, picked up by the prosecution in the pubs around the courts, damaged the idea of impartiality. It wasn’t until the 19th century that an attempt was made to ensure that jurors were truly picked at random, when the Master of the Crown Office closed his eyes and jabbed a dry pen nib into a big book of names of those men qualified to serve.

And for a long time, it was all men. British women were not allowed to serve on juries until the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919. However, property rules meant it was still practically impossible for most women to qualify. A juror had to own property worth at least £10 (worth roughly £4,000 today). Astonishingly, as recently as 1974, eligibility rules regarding property were still keeping women from juries. Homeowners qualified but since single women were routinely refused mortgages and houses belonging to married couples were for the most part registered in the name of the husband, female homeowners were very much in the minority.

These days, eligibility for jury service in the UK extends to almost everyone between the ages of 18 and 70 on the electoral register who has been resident in the UK for at least five years since turning 13. There are, naturally, several causes for disqualification, including having a criminal record of your own. You can be excused if you’re in the armed forces. The rest of us can put it off only once. Bad luck if a second jury summons falls right in the middle of your holiday. Failure to respond to the summons or turn up when required can lead to a £1,000 fine. We’ve come a long way from the 1920s, when women were allowed to excuse themselves from trials that might offend their feminine sensibilities.

While you may be excused from jury service at the judge’s discretion, being well-known is not cause for exemption. In the US, former president George W Bush was called, though not selected, to serve on a jury in Dallas. Tom Hanks couldn’t get out of it, though his presence on the jury for a domestic assault case in Los Angeles caused a mistrial when a member of the LA City Attorney’s office approached the star outside the court house.

In the UK, footballer Carl Fletcher, a former Welsh international, argued that he was too famous to serve on a jury in Plymouth in 2010. The judge disagreed. “Captaining Plymouth Argyle is not sufficient reason for not doing jury service.”

But what does it feel like to sit on a jury? At best, it can feel like being back at school: lots of rules, hours spent sitting on plastic chairs in shabby waiting rooms, boring trials hinging on technicalities that make those long ago physics lessons seem quite interesting. However, what sounds like an exciting trial may turn out to be the beginning of a nightmare. It can be intimidating facing someone on trial for assault, especially when cuts to court services, such as jury restaurants, mean you might end up next to the defendant in the lunchtime queue at a local cafe.

A 2009 report by psychologists at the University of Leicester, led by Dr Noelle Robertson, warned that the nature of the evidence seen and heard by juries in the course of a trial can lead to trauma. Dr Robertson commented: “Jury service is a civic duty, yet we know little about its consequences for the individual. At present, anyone who talks openly about their experiences runs the risk of being charged with contempt of court.”

Prohibited by law from discussing the trial outside the jury room, or from revealing what went on in that jury room even after the trial is over, it’s hard for jurors to get the support they might need. In an interview with ITV News, a female jury member on the 2017 Becky Watts murder trial, said the experience left her “emotionally isolated”.

The juror, who went by the alias Rebecca, said, “During the whole court process, I didn’t eat, I didn’t sleep. I think I lost about three quarters of a stone during the seven weeks… I had no way in which I would process all that information that I was seeing, I had no way to debrief. And once you’ve seen you can’t unsee.”

Is it possible that jury service is too much for the general public? Calls for the abolition of jury trials are nothing new. In 1982, one Professor Hogan wrote to The Times, “Of course trial by jury is one of our sacred cows. But, you know, if we’d long had trial by judge in criminal cases and I were now to suggest that his reasoned and professional judgment as to facts and inferences should be replaced by the blanket verdict of pretty well any 12 men and women placed in a cramped box and holed up there for days or even weeks at a time you would rightly think that I had taken leave of my senses.”

Earlier this year, David Green, stepping down as director of the Serious Fraud Office, said he had “moved from being completely pro-jury” and was instead “edging towards a judge-only model” for complicated fraud, bribery and financial misconduct cases.

A comparatively small number of trials actually come before a jury these days. More than 90 per cent of criminal cases are heard by magistrates, with only the most serious being referred to the Crown Court. The right to a jury trial, enshrined in the Magna Carta, was overturned in the Criminal Justice Act 2003, which gave prosecutors the ability to apply for a non-jury trial in cases where a jury may have been compromised. The internet and the use of smartphones certainly make it harder than ever to ensure that jurors aren’t doing their own research.

Can a jury ever truly be impartial anyway? As Harper Lee wrote in To Kill A Mockingbird: “The one place where a man ought to get a square deal is in a courtroom, be he any colour of the rainbow, but people have a way of carrying their resentments right into a jury box.”

Yet, as Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1789: “It is left… to the juries, if they think the permanent judges are under any bias whatever in any cause, to take on themselves to judge the law as well as the fact. They never exercise this power but when they suspect partiality in the judges; and by the exercise of this power they have been the firmest bulwarks of English liberty.”

“Guilty or not guilty” is still a question we take seriously. And if we should ever be stuck in the dock, most of us would still want our peers to consider it on our behalf.

Christine Manby has written numerous novels including ‘The Worst Case Scenario Cookery Club’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments