International Women's Day 2017: The girls defying all the odds to become scientists and engineers

Young women are discouraged from studying male-dominated subjects in Africa. But thanks to Ghana's first science academy, gifted girls can pursue STEM subjects. Rhianna Ilube meets three students paving the way for others

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

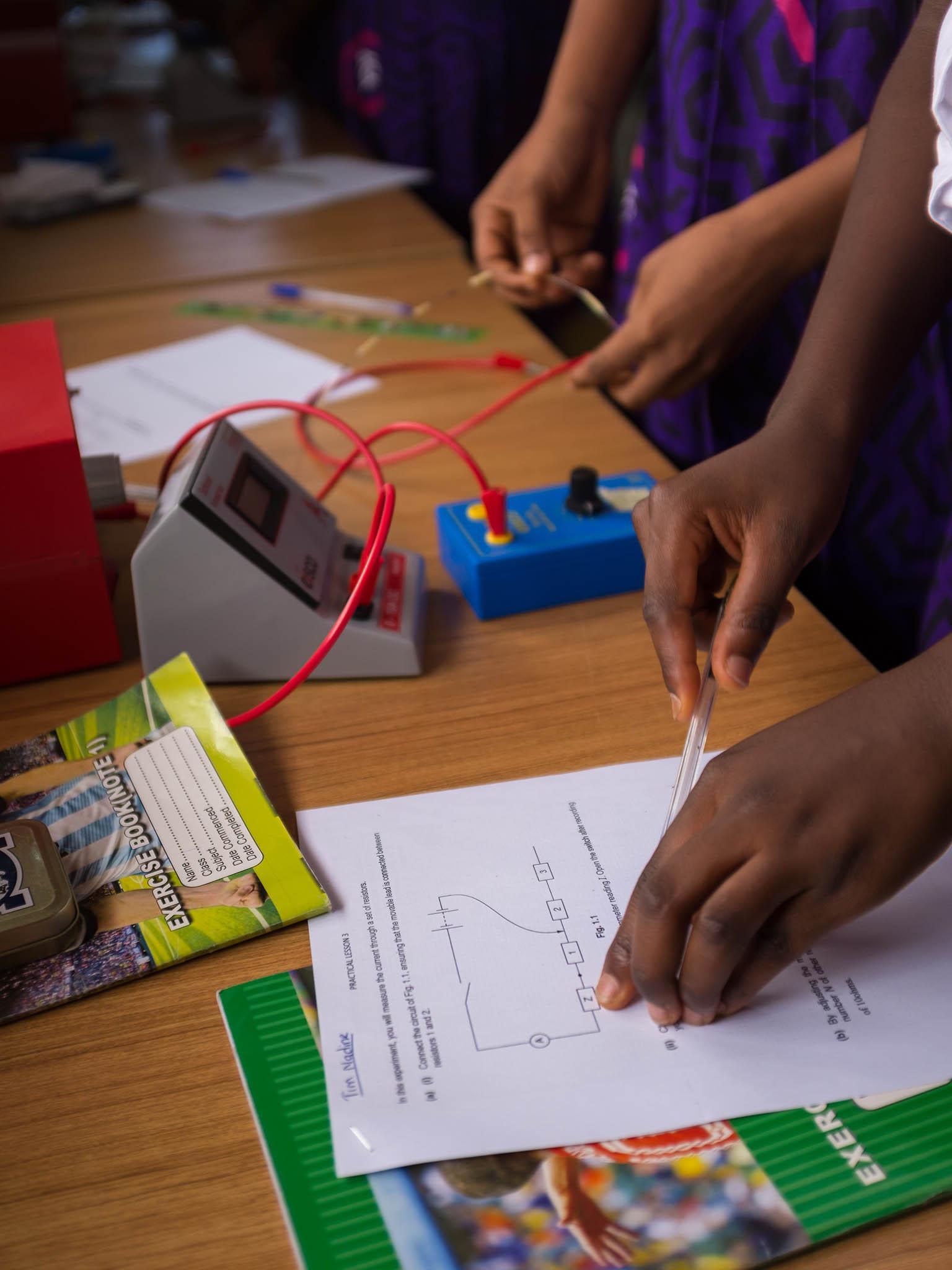

Your support makes all the difference.Africa’s first science academy for gifted girls opened in Ghana in August 2016. Last year, 150 girls applied for 24 places, hoping to attend the new one-year academy.

These girls are statistically rare. Worldwide, women are still remarkably underrepresented in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) industries and university courses. Many girls are actively discouraged from pursuing science in high school, assuming they complete their secondary education.

In Ghana, 21 per cent of girls are married before they are 18, with rates as high as 39 per cent in the northern part of the country, according to Unicef's State of the World’s Children 2016. To mark international women’s day, I met three of the pioneering girls at the African Science Academy (ASA) to find out what helped them get to this point, and what they need to continue their chosen path.

Emmanuella

Emmanuella is 18 years old, born and raised in the capital of Accra. She has an eye for design and a love of computers.

Her mother is a trader, selling goods on the city streets, and her father is a carpenter. “Life is normal,” she says. “In my town, you don’t get a lot of people to inspire you.”

As a child, her mother aspired to become a nurse. “Her father was proud of her…but unfortunately, he died. Nobody else was willing to allow her an education. She believes that if she could have made it, her children definitely can.”

At 6, Emmanuella’s parents could not afford her school fees, so she spent a year at home helping her mother work. “I was happy because I didn’t have to go to school! But when all my friends went to school…I felt as if I was not doing anything here.” So her mother worked hard for the funds to get Emmanuella back into school.

Growing up without electricity was not ideal; a popular TV program called Ghana’s Most Beautiful was on, but she had no means of watching it. Yet the situation had its benefits. Without the distraction of TV or radio, she says there was nothing to do but “read our books”.

But it wasn’t just a time to read, it is also the reason she is interested in how things work, as after being tired of doing homework by candlelight, at 12 Emmanuella built a torch-light from scratch using a bulb, wires, spare batteries, and a box. “When my father bought a radio, I broke it apart to understand the mechanics.”

However, as she approached high school Emmanuella thought she wanted to swap the sciences to study business. But her maths teacher and mother, citing her potential, refused to let her, and from here, her talent continued to grow. “Whenever there was a maths quiz, my physics teacher would encourage me to be a part of the team. Now I see that he was trying to tell me something: I can do it.”

At 17, her school counsellor encouraged her to apply to the new ASA for gifted girls. Intrigued, she returned home and told her parents about the opportunity. They were not convinced; she was expected to start working and save money for university. She said: “It was my own decision, and I decided to apply”.

Joana

Despite being born in predominantly English speaking Ghana, Joana spoke French. At a young age, her family moved to neighbouring French-speaking Togo, but a few years later her father suffered a stroke and he couldn’t work. Consequently, the financial situation became very difficult. Her mother borrowed money, sold land, hired help – but it wasn’t enough.

At primary school, Joana’s intellect shone. And as long as Joana remained at the top of her classes her uncles back in Ghana would fund her education. The pressure was on, but Joana enjoyed studying. “I am an indoor girl. I don’t really go out. If I see people playing football, I might join them. I prefer to read a book, if I’m not doing maths and science,” she said.

Joana completed high school in Togo with glowing grades in the French Baccalaureate. But after turning 18 in 2013 – along with her family – she returned to her country of birth, but she couldn’t attend university here without completing high school again – this time in English. Joana described it as “ a tough decision” but took it anyway. “I like school and I don’t like to rush in life. I think that whatever God has planned, I will become,” she added.

Joana watched on as her friends in Togo started university, as she struggled with the English language. But ever determined to overcome life’s barriers, she excelled. In her final year, she was chosen as the first female ever to represent her school in the prestigious National Maths and Science Quiz, which she said “was a great achievement in my life”.

She had always planned to study medicine at university but during her final year, she begun to change her mind. “My teachers told me: as you are good at maths, engineering would be good for you. But I thought, ‘isn’t engineering a male field?’” Her perception was altered at the National Maths and Science Quiz, where Joana met Dr Elsie Kaufmann from the University of Ghana. “Here was a great female engineer. I decided I wanted to become like her one day,” she said.

When she heard about the ASA she immediately knew she would apply. “I will say one truth: I like maths a lot. When I heard about this school for science and maths, I said: no way! I will go by all means,” said Joana.

Ramlah

Ramlah grew up in Addis Ababa and went to one of the best schools in the country and was an independent child. “My mum told me I behaved like an adult. I wouldn’t go out to play. I would stay inside and do my thing.”

Her own thing involved completing the tough extra assignments her father would give her every day, from the age of 2. “We had to do it before he came back home. I did everything to the best of my ability. I had this laminated notebook. I would write out A-Z and make sure it was perfect,” she said.

Both parents were strong believers in the power of education for their children. Her mum quit her job and gave up her own dream of university to help Ramlah and her younger siblings study. “My extended family are really religious. They look at us and say: you call yourself Muslims? My dad says: you should be close to God. God gave you a brain. He expects you to use it well.”

At school, Ramlah started exploring her academic talents. In class, she was brilliant but often disruptive. “I was good at maths, but I couldn’t sit for too long.” In response, her dad, an accountant, told her: “I’ll get you a tutor who will teach you everything fast, but only if you stay quiet in class.” And she did just that. When Ramlah heard about the ASA, she was determined to apply. But she had already had an offer to study medicine in Ethiopia, and her father didn’t want her to move to Ghana alone at the age of 18.

So, she adopted a different strategy: persuading her mum, who then convinced her husband to let their daughter move to Ghana. And today she is a student at the African Science Academy in Ghana, continuing to do her own thing.

To be continued…

With natural talent, supportive parents, and academic mentors, these girls from very different backgrounds have shone. They met and became friends at the ASA, supported by fully funded scholarships.

Emmanuella, inspired by her childhood, wants to study electrical engineering. “My brother suggested I consider electrical engineering, but I thought it meant to be an electrician. When I came to ASA, I learned about the various engineering fields. Using my earnings, I will open orphanages and bring up street children. Whether they are interested in STEM or not, I will bring out their potential.”

Joana sees herself in either Ghana or Togo. “I want to help the French system. The English system is so impressive. French-speaking students don’t have the same opportunities or funding – even though they are brilliant students.” Joana also wants to study engineering; she is particularly interested in the potential of solar and electric cars to transform Africa.

Influenced by her programming classes at ASA, Ramlah now wants to study computer science. “I want to think of exciting ideas and bring them back to Africa, using technology to improve access to education. We have a lot of great systems here but we are always trying to adopt westernised approaches.”

Such feats don’t happen by magic. As remarked a fellow ASA student: “I cannot rule out the fact that I am a girl. If I do not get a scholarship and I am still not in school over the upcoming years, the pressure to become married will grow, as I will be viewed as someone who does not have any other options…I do not wish to be out of order in the 21st century.”

To reach their goals, the girls depend on securing funding to pay for university tuition. They also need the continued encouragement of their families to prioritise an education and career, over marriage and children. They plan to surround themselves with positive people who will support them on their journey. In 2017 the future looks bright. The girls have already made their parents proud.

Rhianna worked as a progression mentor at the African Science Academy in 2016. She now works for as the UK networks coordinator for restless development, a youth-led development agency. Follow her @ririword

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments