Are we all capable of killing someone? Here’s what a criminologist has to say

The new BBC drama ‘Inside Man’ explores the idea that we are all capable of killing someone – it’s just a question of meeting the right person. Tom Ough talks to an expert to uncover the truth behind the theory

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Are you capable of killing someone? What if you’re in a particularly bad mood? What if someone’s really asking for it? In the BBC’s new drama Inside Man, David Tennant’s character, a vicar, is falsely accused of owning indecent images of children. He faces the following everyday dilemma: should he allow his accuser to spread the falsehood? Or should he just bump her off when he has the chance? Thus begins a show that explores the idea that “everyone is a murderer. You just have to meet the right person.”

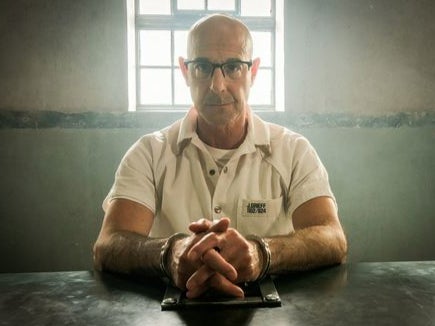

Those words are uttered by Stanley Tucci’s character, Jefferson Grieff, who speaks from experience: he is locked up on Death Row and awaiting his execution. But is he right? Is there, inside every non-murderer, a murderer trying to get out? David Wilson, professor emeritus of criminology at Birmingham City University, thinks not. He, too, speaks from experience, having spent his professional life working with men who have committed murder, supervising them as a prison governor and interviewing them as an academic.

The idea that everyone is a potential murderer, says Wilson, is “nonsense”. (Phew.) We all have bad days, Wilson says, “and we all meet people we don’t particularly like. But if we were killing in the way that [Tucci’s character] said we do, then the numbers of murderers would be so much higher than they actually are.” Serendipitous meetings do not a murderer make.

The murder rate, he says, has been in long-term decline for decades. There were 710 homicides recorded by the police in England and Wales in 2021/22, which was an increase from the 570 of the year before, but much lower than the 1,047 in 2022/23. Wilson refers to the point made by the American academic Steven Pinker that humanity is, in general, becoming less violent. Yet our appetite for murder dramas and podcasts has never been so ravenous. Dahmer, a series about the American serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, is currently the most-watched show on Netflix. The topic of murder, says Wilson, “is something that’s a zeitgeist at the minute”.

Why? We shouldn’t worry, Wilson says, that we’re much more preoccupied by murder than our forebears. “Murder has always been a popular news and dramatic trope since the early Victorian period. I wouldn’t even argue that we are more interested now than our ancestors – after all, hanging days were public holidays and attracted huge audiences.”

Those who find murder shows riveting might, in another era, have been in the front row at public executions. The human fascination with death is deep-rooted and ancient. “We’re drawn to stories of those kinds for all kinds of reasons,” says Wilson. “But the writer, the storyteller, uses those stories because they provide drama.” In 90 per cent of British murders, he says, the culprit is caught, and they are often someone known to the victim. “But that criminal logical reality doesn’t make for very good drama.”

Instead, TV writers tend to focus on two main tropes: unsolved murders, and the idea that we’re all potential murderers. The latter is an idea that is as compelling as it is horrifying, so it should be no wonder that writers turn to it so frequently.

As Wilson says, though, it’s not true. And not only is it untrue, it’s also a rather murderer-friendly way of looking at things: it’s an argument commonly set forth by murderers attempting to elicit sympathy through relatability. “And by implying that we’re all one step away from being murderers, they try to get off that hook of personal responsibility. That’s really what my job is, often: to make them realise, ‘No, no, it was you that did this, and you have to make amends, as far as you are able, and we have to help you work out how you got to the position where you took other people’s lives.’”

Serial killers in particular, Wilson says, “have always liked to present themselves as somehow more willing to go that extra step that all of us would take if only we had just as much courage and insight as they did”. He recalls a conversation with Dennis Nilsen, the Scottish serial killer and necrophile who murdered at least 12 boys and young men. Nilsen described himself as “an ordinary man, come to an extraordinary conclusion”, he explains – similar to the argument made by Tucci’s Inside Man character. “And you had to say to Dennis Nilsen, ‘You’ve never been an ordinary man. And this “extraordinary conclusion” is a crime. It’s called murder, and people don’t do that.’”

To posit murder as something anyone might do – or to write a drama animated by that thought – is to do the murderer’s PR for them, Wilson says. “A lot of the serial killers that I’ve worked with are very keen on manipulating their own PR or image. If you prioritise their narrative, if you prioritise their thinking about what they’ve done, you allow them to capture the narrative.”

In some cases, films and TV shows give killers a veneer of glamour. Wilson cites The Silence of the Lambs, as well as the novel, by Thomas Harris, on which the film is based. “You’ve got the evil genius who talks about Florentine architecture and fine foods and loves Bach’s toccatas. Trust me, I’ve never encountered a serial killer who had any of those interests.”

Instead of doing this accidental PR work, he adds, we should consider the social problems that cause and accompany murder. “In Dahmer’s case, it was homophobia, for heaven’s sake, and the failures of our police, as it was in the case of Dennis Nilsen.”

Tennant played Nilsen in a three-part drama, Des, in 2020 – a show that Wilson says did a good job of telling the story in a way that was not overly sympathetic to Nilsen. “It prioritised the voice of Brian Masters, Nilsen’s biographer, who effectively brought to life the sense of questioning Nilsen and not giving him the narrative. And the other person within the drama was the detective chief inspector who arrested Nilsen, and that therefore brought the victims into the story.”

In contrast, Tennant’s character in Inside Man gives the appearance of stumbling onto the brink of a potential murder. “Yesterday,” his wife tells him, “you were the vicar. Today you are a man who assaulted a woman and locked her in his cellar because you were so desperate to protect your son.”

So what does Wilson think of dramas like Inside Man? “I don’t disapprove,” he says, somewhat surprisingly. Tennant’s character might be portrayed over-sympathetically, but such shows, Wilson hopes, might contribute to improved public discourse about murder. “What I want to do,” suggests Wilson, “is harness the public’s fascination with those kinds of dramas, and use that fascination to get the public to think about other things.” Serial killers target vulnerable groups, he says, and we would do well to reflect on that. “If we challenge homophobia, if we have a grown-up debate about sex work, if we think about the place of the elderly in our culture, we do a lot more to reduce the incidence of serial murder.”

It remains to be seen what Inside Man adds to the conversation. But thanks to Wilson, we can at least watch the show without the fear of unexpectedly committing a murder.

David Wilson and Emilia Fox present the podcast ‘If It Bleeds, It Leads’. They will be in conversation at the Emmanuel Centre, London, on 28 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments