Coronavirus: Our need for physical affection and why the pandemic could be harming our instincts

The discovery of germ theory more than a 100 years ago had a detrimental impact on parenting, writes Fredrick Kunkle, and coronavirus could be pushing us away from each other again

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There was a time when families shared toothbrushes and dinner utensils, and travellers who needed lodging for the night shared a bed with strangers of the same sex. It wasn’t unusual to find a public drinking fountain with a single tin cup for everyone to use.

Germs changed all that. More than a hundred years ago, germ theory – the discovery that microorganisms such as bacteria and viruses caused disease – had a profound impact on almost every aspect of human behaviour, just as coronavirus could do after the current pandemic ends.

Sharing beds, whether at home or in public lodgings, became unacceptable; laws against spitting in public went on the books; and restaurants began requiring waiters to shave their beards and moustaches. Out went the fashion for long skirts and Victorian decor with its heavy drapery, where germs might lurk. In came an entire industry of sanitary products and disinfectants, such as Listerine, and spotless porcelain toilet fixtures.

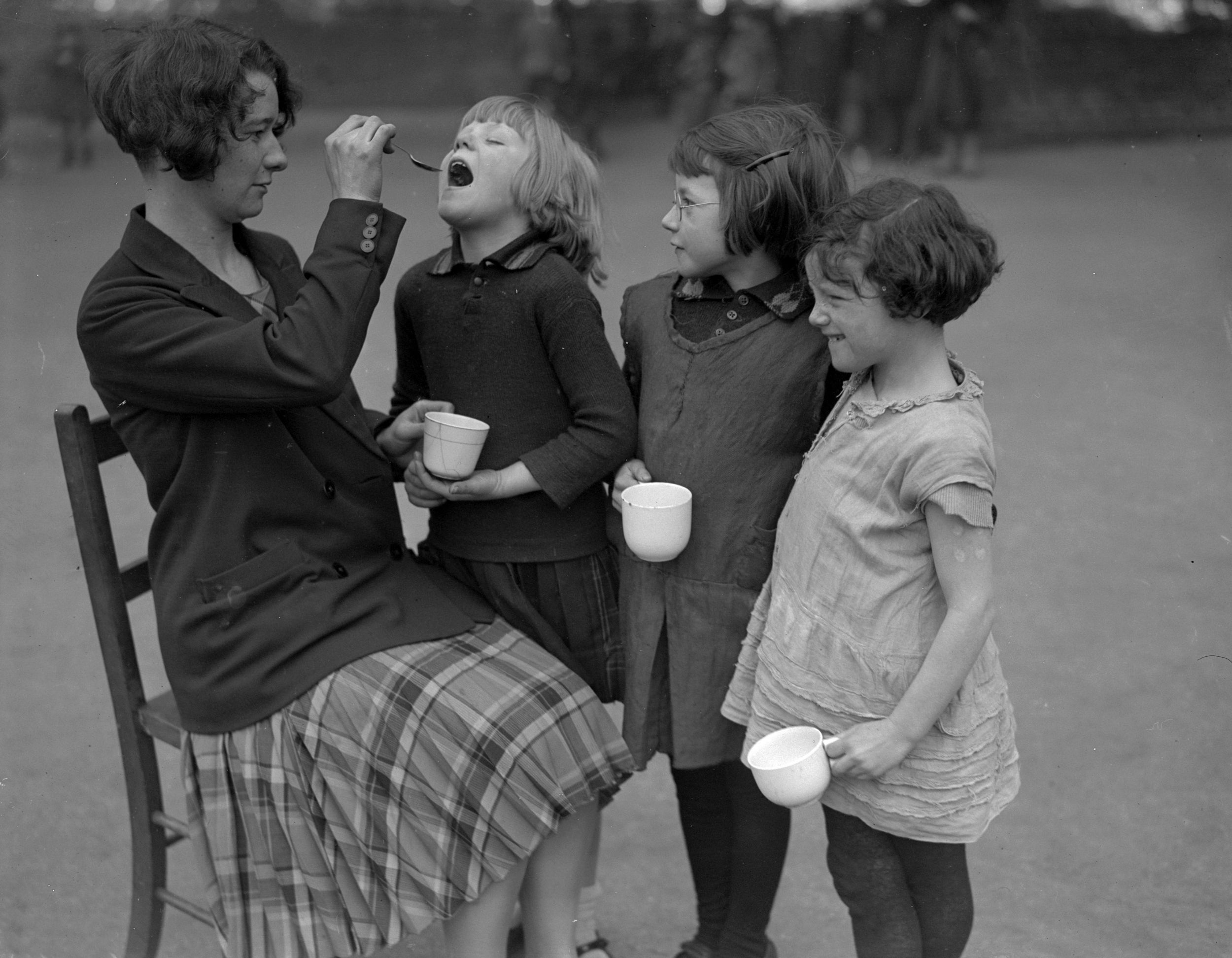

One of the most poignant side effects from the discovery of pathogens was on child rearing. By the end of the 19th century, mothers and other primary caretakers became cautious about cuddling or touching their children for fear of breeding deadly infections. Parents, heeding the advice of physicians and even the US government, adopted a style of care that was chilly and aloof.

The new approach to sanitation helped reduce frightening levels of infant mortality. In 1870, 175 of every 1,000 infants died in their first year of life in the US; by 1930, the number decreased to 75. Yet the hands-off approach that kept children safe from germs also ran counter to the instinctual need for physical affection that all primates, including humans, have. And its absence produced damaging consequences of its own.

“I found these just heartbreaking stories about mothers who were afraid to touch their children, to show physical affection to them,” says Nancy Tomes, a professor of history at Stony Brook University in New York and the author of The Gospel of Germs: Men, Women and the Microbe in American Life.

All that would shift again by the middle of the 20th century, when psychologists such as John Bowlby and Harry Harlow exposed the potentially traumatic side effects of remote parenting on child development.

Bowlby, through his work with troubled children, and Harlow, using baby monkeys, demonstrated the evolutionary necessity of physical touch and affection. Their work also pointed the way forward for new child-centred parenting theories such as those popularised by Benjamin Spock and Berry Brazelton that rejected the sterile doctrines of the past.

“It is heartbreaking to think that ... a certain generation of people [had] that kind of fear of touch,” says Tomes. “God knows what it did to their sex lives.”

In ancient times, disease was thought to be the result of an imbalance of body fluids or an affliction from the gods. Later, scientists suspected that illnesses might be transmitted through the air or water, but weren’t clear how.

With the development of compound microscopes in the 1600s, scientists got their first glimpse of microorganisms. In the mid-19th century, Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch demonstrated that bacteria were the agents of some diseases. By the close of the century, scientists identified viruses.

These breakthroughs revolutionised medicine and public health, leading to new treatments and preventive measures for cholera, tuberculosis and other infectious diseases.

Germs also changed the way people lived.

Wicker – which was thought to be germ-resistant – became the seating of choice. Refrigerators and vacuum cleaners were marketed not only as labour savers but as necessities for good hygiene. When the DuPont Cellophane Co brought out plastic wrapping in the 1920s, the product was hailed as a sanitary innovation for keeping food and other personal items. (“No admittance to germs,” an ad says.)

By the end of the First World War, toilet paper appeared. Even bedding changed: sheets lengthened in size so that the exposed end of a clean one could be folded down over the blanket, which was apt to be reused.

Germs changed more than household products and furnishings, too. In 1888, the Wife’s Handbook warned mothers that a single touch was teeming with deadly germs that might harm her infant, and public campaigns urged caution when preparing family meals.

“If you were a mother that didn’t keep the kitchen clean and your baby got some catching disease, it was your fault,” Tomes says in an interview. “I’m convinced that a lot of the reason that American food ended up being so overboiled and overcooked was, they had to get the germs out of it.”

What Harlow found is that the monkeys visited the metal mother only for as long as it took to feed. They spent the rest of their time clinging to the terry cloth mothers

The dread of an unclean kitchen carried into the nursery. Deborah Blum, in her book Love at Goon Park: Harry Harlow and the Science of Affection, says physicians began to warn mothers and other caretakers about the risk of any physical affection.

John Watson, a pre-eminent psychologist in the early 20th century and president of the American Psychological Association, went so far as to tell parents that showing physical affection to a child could have harmful psychological effects.

“When you are tempted to pet your child, remember that mother love is a dangerous instrument,” Blum quotes him as saying. Watson warned of “serious rocks ahead for the over-kissed child”.

Watson’s behaviourist views – built on the Pavlovian notion that much of human and animal behaviour is reflexively conditioned by stimulus and reward – reflected a widespread belief that the bond between mother and child arose only from a need for food. A child needed a sterilised bottle of milk from his caretaker and little more, or so the thinking went.

“All of it, the lurking fears of infection, the saving graces of hygiene, the fears of ruining a child by affection, the selling of science, the desire of parents to learn from the experts, all came together to create one of the chilliest possible periods in child-rearing,” Blum writes.

All of this would change around theSecond World War when Bowlby, the originator of attachment theory, observed the damaging effects of separation on British children who had been removed from their parents and evacuated to safer areas. His work fitted with research by others into the psychological effects of abandonment and isolation on children in foundling homes.

Bowlby, who began his career as psychiatrist at a centre for troubled children in London before the war, was struck by the way the youths often exhibited signs of rage, desperation and despair. He connected this to their inability to form close attachments to primary caretakers, either because of physical separation or other circumstances, such as parental depression.

Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, an anthropologist and author of Mother Nature: A History of Mothers, Infants and Natural Selection, says in her book that Bowlby, through a keen interest in evolutionary theory, came to believe that attachment between parent and child was one of the most important determinants of a child’s mental and physical health.

This is because people, like all primates, are social animals. Their complex brains are slow to mature, and their offspring remain vulnerable longer than other species. Humans must depend heavily on others for nurturance and care if they are to survive.

Bowlby believed that every child is born with an instinctual awareness that having a strong emotional bond with a caretaker can mean the difference between life and death. He also believed that anything that damages the formation of that attachment would have a lasting impact on the child’s mental health.

Those theories also found support in Harlow’s monumental research with baby monkeys in a University of Wisconsin laboratory.

Harlow was a psychologist who was interested in whether primates had an instinctual need for physical touch and affection. To test his theory, he created different kinds of surrogate monkey mothers. One, which was made of rubber foam and terry cloth, was soft; the other was made of bare wire mesh but equipped with a feeding bottle.

What Harlow found is that the monkeys visited the metal mother only for as long as it took to feed. They spent the rest of their time clinging to the terry cloth mothers.

Further experimentation showed that baby monkeys possessed such a powerful need for maternal attachment that they would even cling to a “monster mother” that was designed to be cruelly inhospitable when the monkeys approached to cuddle. Harlow also found that monkeys that were deprived of physical contact began to exhibit highly abnormal or pathological behaviour.

Harlow’s and Bowlby’s insights set the stage for a shift towards child-centred and emotionally connected parenting that remains in fashion today. But it came too late for generations whose upbringings were marked by an excessive fear of germs – like the person who approached Tomes after she gave a talk about her book.

“A woman came up to me afterward and said, ‘I never understood why my mother wouldn’t be physically affectionate with me. But now I understand: she was terrified of making me sick,’” Tomes says. “’Now that we’re in a pandemic, you become aware of the trade-offs.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments