The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

How to use your hands when public speaking

The use of hands can be highly effective prop, but shouldn't be overused

Somewhere along the way, most of us have been given advice about public speaking that goes something like this: Don't use your hands too much. Just keep gestures to a minimum so people can focus on your words.

Yet research shows that it's actually effective for a presenter's hands to do plenty of "talking". They just need to be saying the right thing.

For instance, consultant Vanessa Van Edwards studied famous TED talks and found that the ones that went viral and became wildly popular featured the speakers who used their hands the most. The least-watched TED talks had an average of 124,000 views and used an average of 272 hand gestures. The top-ranked ones, meanwhile, had an average of 7.4 million views and 465 hand gestures during the same length of time.

"When really charismatic leaders use hand gestures, the brain is super happy," she said. "Because it’s getting two explanations in one, and the brain loves that."

The problem for most people, of course, is figuring out how to use the right gestures that reinforce their verbal message—all while anxiously trying to remember what to say. So what's effective and what's distracting? The Washington Post checked in with five speech coaches and body language experts to better understand the right and wrong ways to use your hands when you're speaking in front of a crowd.

"Do what comes naturally" may be common advice from presentation coaches, and it's easy to see why they say it: Get too choreographed with your gestures, and you'll forget your speech or look like a seven-year-old pantomiming to pop radio.

But there are some instances where having a pre-planned descriptive gesture at the ready can really help.

If you're talking about a small thing, pinch your fingers. If it's a really big point, don't be afraid to gesture your hands in the air. To help audience members keep track of what you're saying, hold out one hand to describe the benefits of an issue and then the other to describe a list of downsides, Van Edwards suggests.

And "anytime you say a number below 5, you really should show that with your hand," she says. "It helps people remember the number; it helps us believe the word. It's a way we underline, like a nonverbal highlighter, the word people should remember."

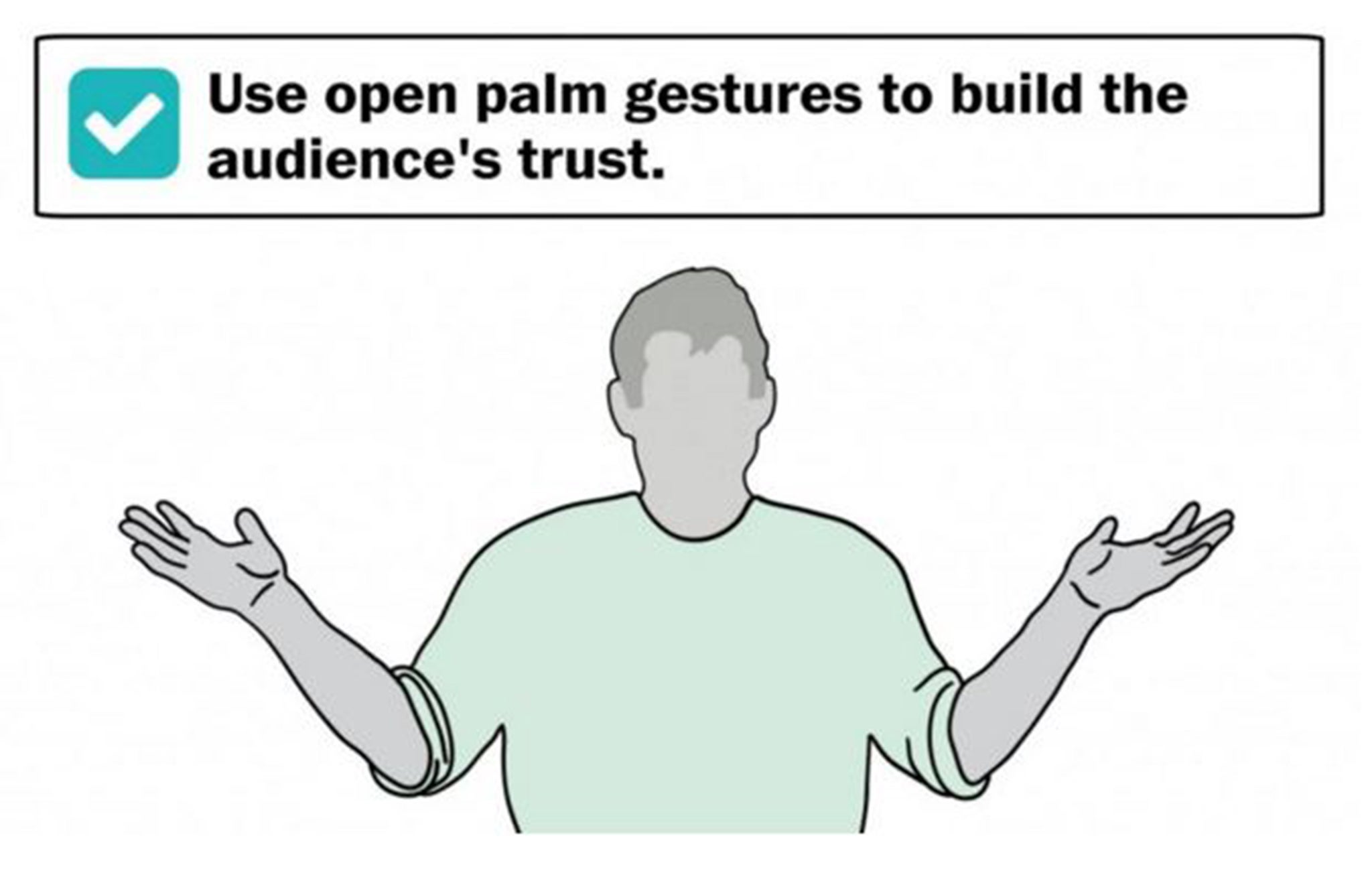

One of the few universal recommendations we heard was to make outstretched gestures to the audience with open palms. That may be because it has evolutionary underpinnings. Mark Bowden, president of a Toronto-based communications training firm, refers to it as "no tools, no weapons." Everything from the handshake to the "hands up" movement people give to police provides proof that you have nothing to hide.

"If I'm showing open palms, it signals to everybody that I've got nothing to harm you and I'm exposed," he says.

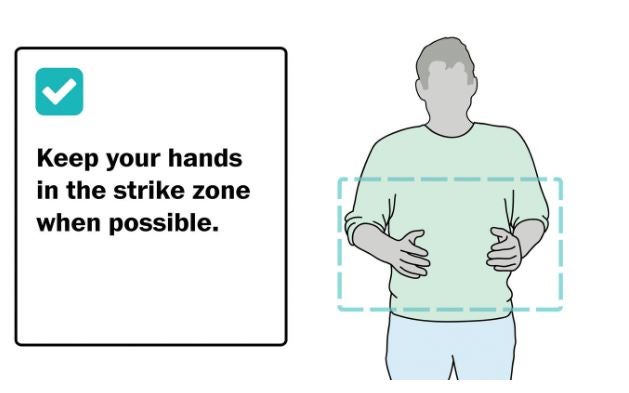

Generally, it's a good idea to keep your hands in what some speech coaches refer to as the "strike zone"—a baseball reference that in presentations refers to the area from your shoulder to the top part of your hips. "That's the sweet spot," says Van Edwards. "That's a really natural area for you to gesture." Going too wide or too high with your arms too often can be distracting, but again, presentation experts say it's not a hard and fast rule. Keep it in mind, but don't worry about breaking it occasionally.

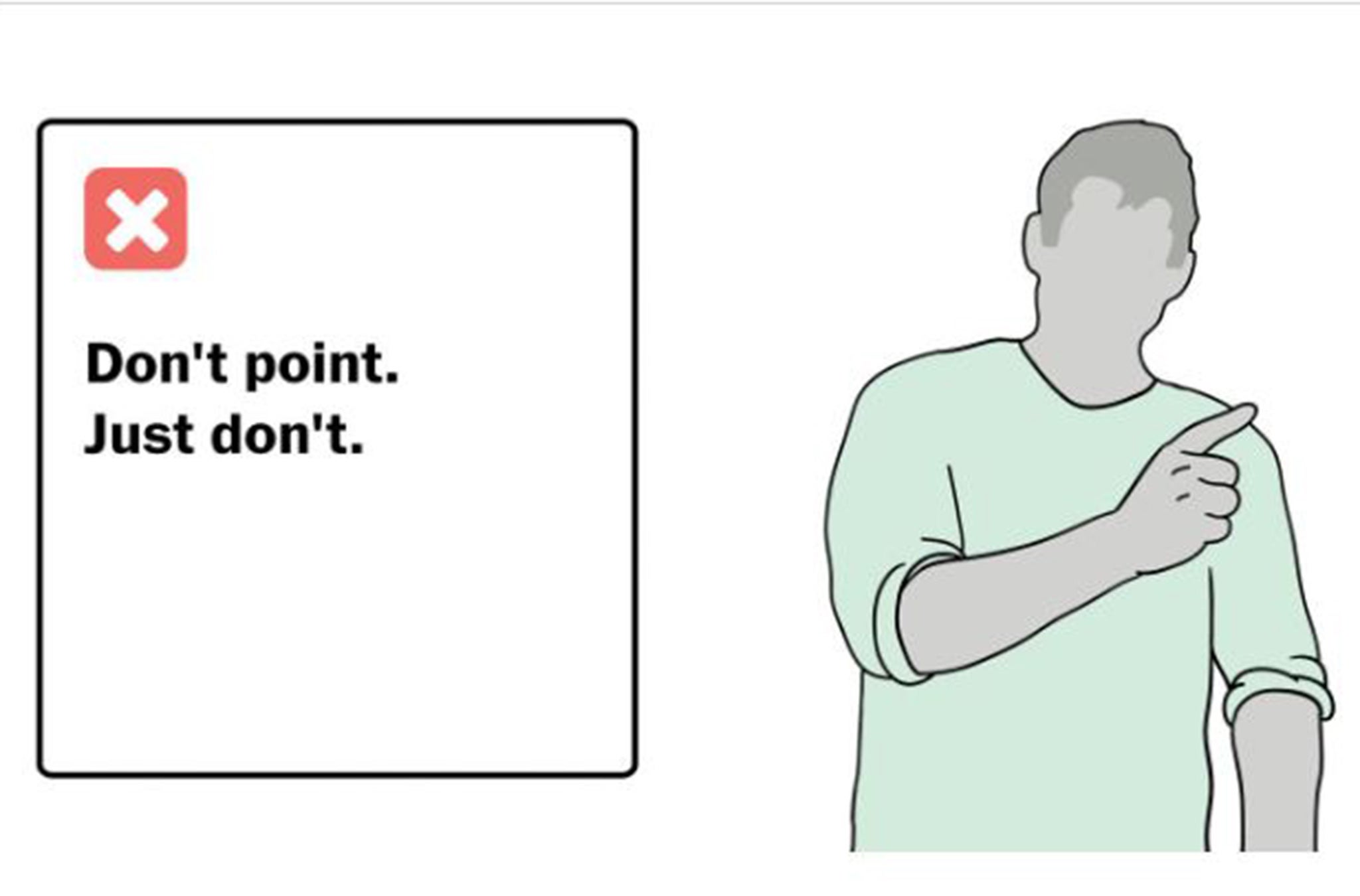

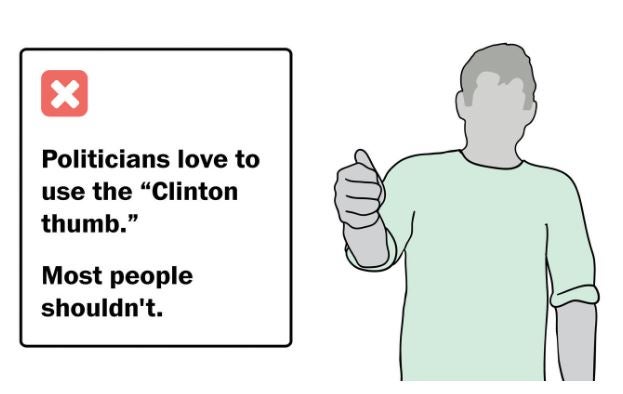

Meanwhile, one of the few repeated no-nos we heard was to avoid pointing. It can look aggressive, unwelcoming and off-putting to many in the crowd. "Audiences hate it," Van Edwards says. It's enough of a problem, in fact, that some politicians have created substitute gestures to avoid it (see the "Clinton thumb" below). For most people, it's better to find a descriptive or more open gesture to emphasize a key issue.

It's been dubbed the "Clinton thumb"—when a politician makes a fist and rests his thumb on top of it. Seen as a way to coach speakers out of pointing, pounding their fists or looking too aggressive, it's been used by everyone from John F. Kennedy to former U.K. Prime Minister Tony Blair to Bill Clinton, whose use of it has been both mocked and mirrored.

While the gesture may be helpful for some politicians who have had to carefully balance how aggressive they appear (Van Edwards, for instance, thinks Obama's thumb-on-fist is effective), it just doesn't look natural for most of us.

"I never see a human being do that move who’s not running for office," says Jeffrey Davenport, a speaker coach who works for the presentation firm Duarte. "Occasionally you’ll see CEOs do it. They like to imagine themselves in that same rare air as a president of the United States. But most people just don’t do that at a party."

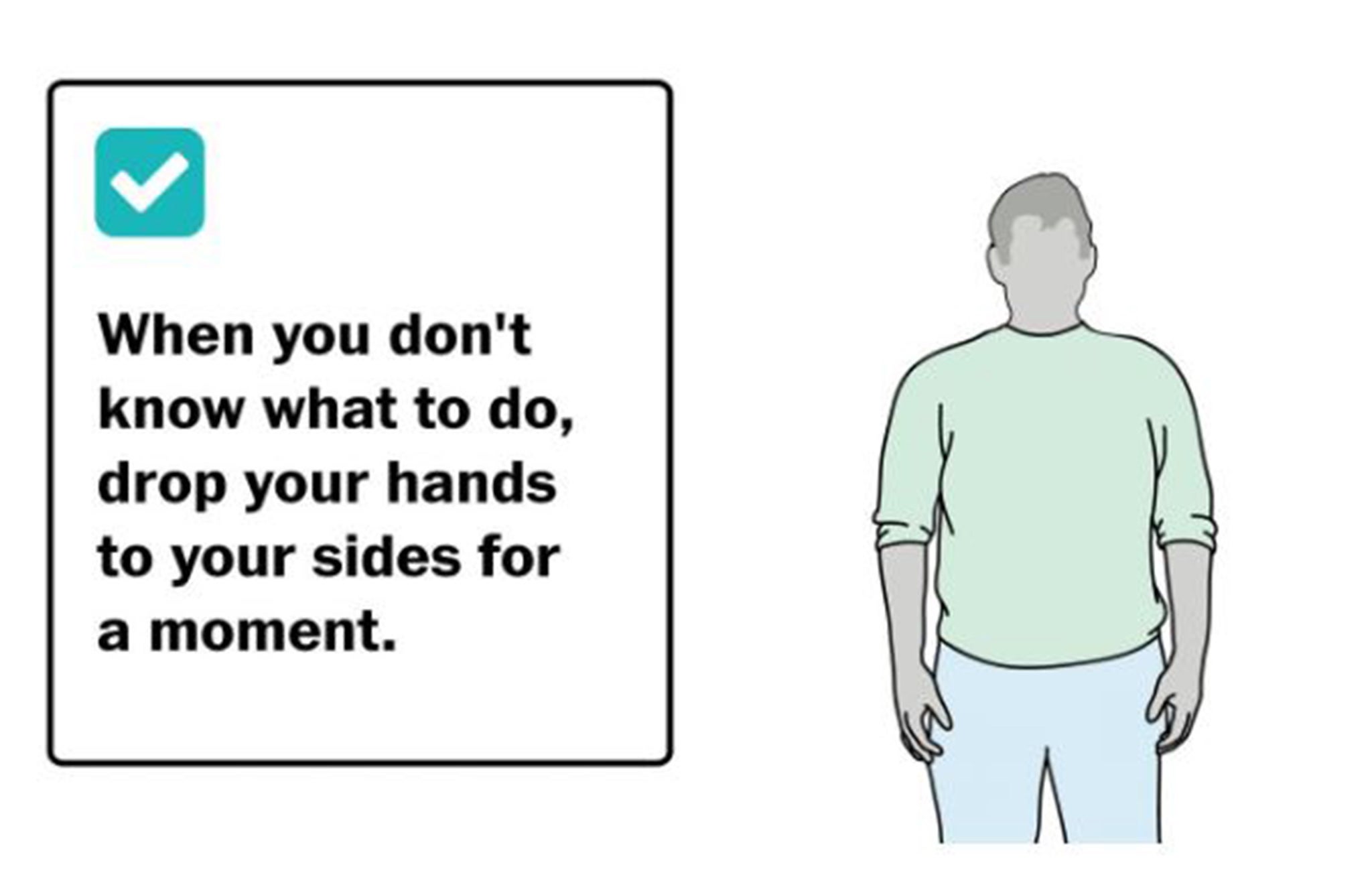

However prepared you may be, there inevitably comes a moment when you realize you've done exactly what you shouldn't. Perhaps you've spent the last five minutes pointing, or something just doesn't feel right with the gestures you're using.

When that happens, says Jerry Weissman, a San Bruno, California-based corporate presentations coach, he tells people to briefly drop their hands down to their sides. It serves as a reset button of sorts. "It's like home base for the arms," he says. But only keep them there temporarily—"touch and go," as Weissman calls it.

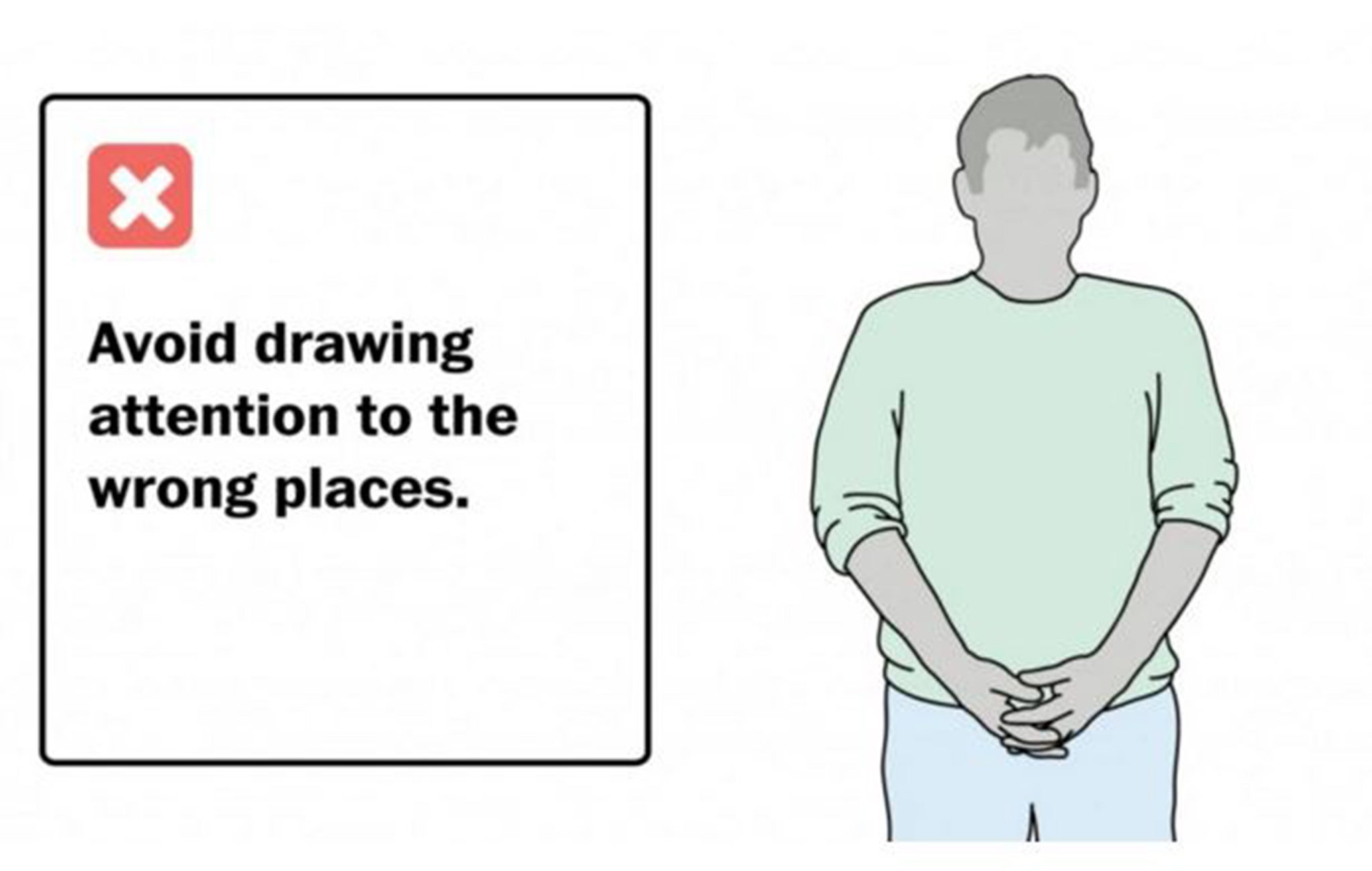

As with most of this advice, everything in moderation is fine. But speakers who spend too much time clasping their hands in front of their groin area—often out of not knowing what to do—inevitably draw attention to the wrong place.

Moreover, it keeps their hands still and unable to be used in more effective ways. Weissman calls it the "fig leaf," and again suggests breaking the habit by dropping arms to the side for a brief moment.

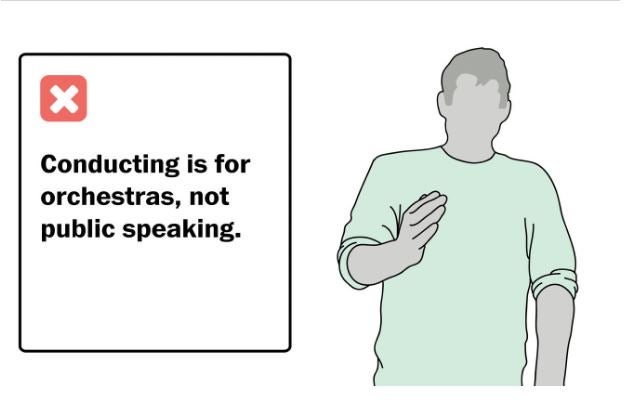

People writing a great speech are careful to mix up the length of their sentences, the tone of their voice and the volume of their words. It's important to do the same with your hands, avoiding repetitive gestures such as slicing the air or chopping it into an open palm for more than a moment or two.

"I always call it conducting," says Gina Barnett, an executive communications coach who coaches TED conference speakers. "When you do anything in a repetitive pattern, [the audience] is gone. It's boring."

Women in particular should be careful of it, says Van Edwards. Research has shown that women's voices stimulate parts of the male brain used to decipher music. "If a woman has a very repetitive gesture, it could make it seem like she's not saying anything new, that she's droning on and on" to the men in the audience, Van Edwards says, as they are already prone to hear her voice as more singsong. "A metronome-like gesture actually encourages that thought, even if she is saying something different."

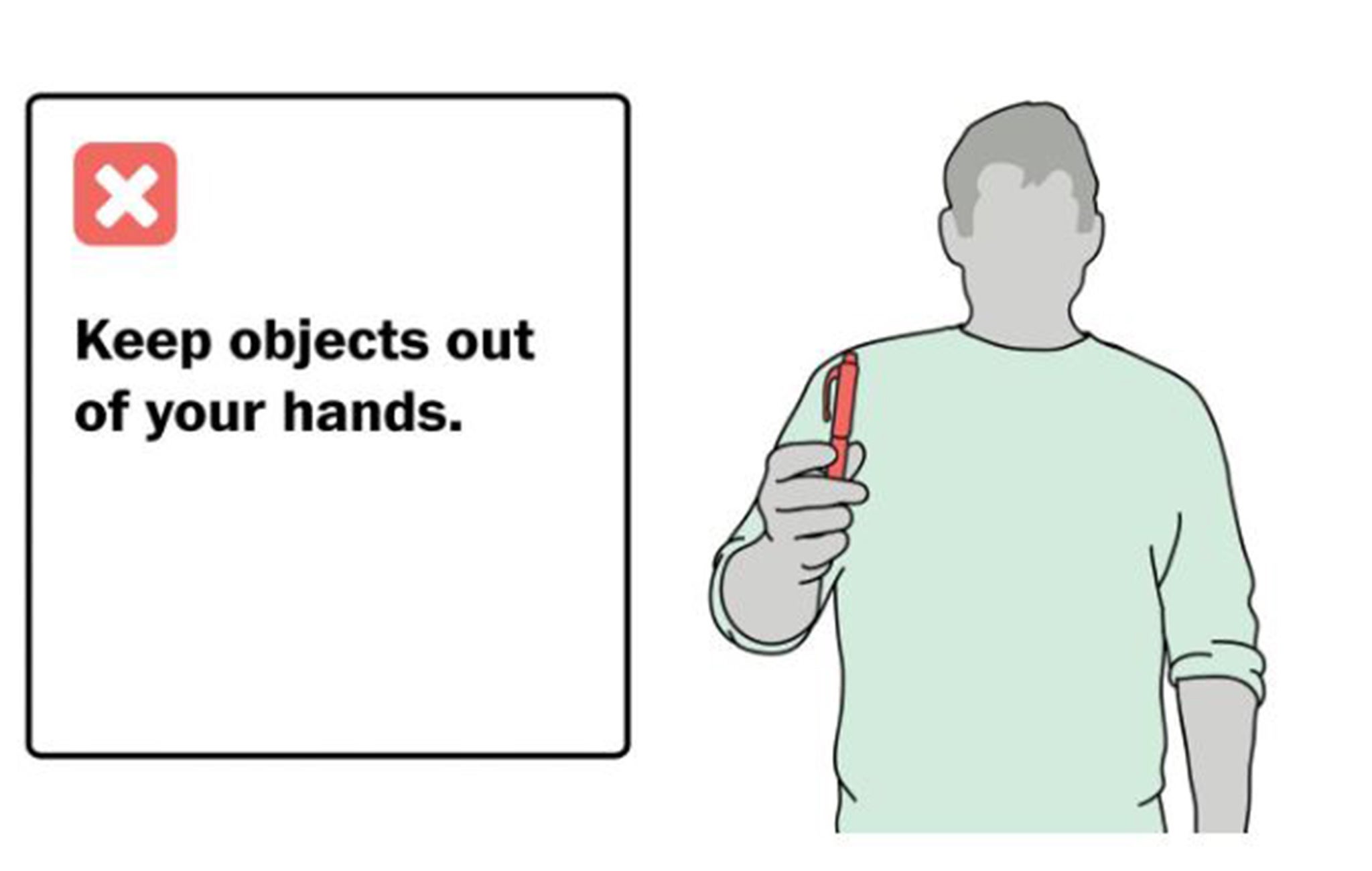

Barnett says she commonly sees clients whom she's coaching stand up with a pen in their hands, give a presentation, and not realize they've spent the entire time clicking the pen's top. Other people rustle papers they're holding or beat their thumbs on a table or podium.

These are all examples of fidgeting, she says, which distract the listener or make the speaker come off as nervous. "That's why I always say 'don't have anything in your hands,' " Barnett says. "People fidget, and they're often clueless to what they're doing."

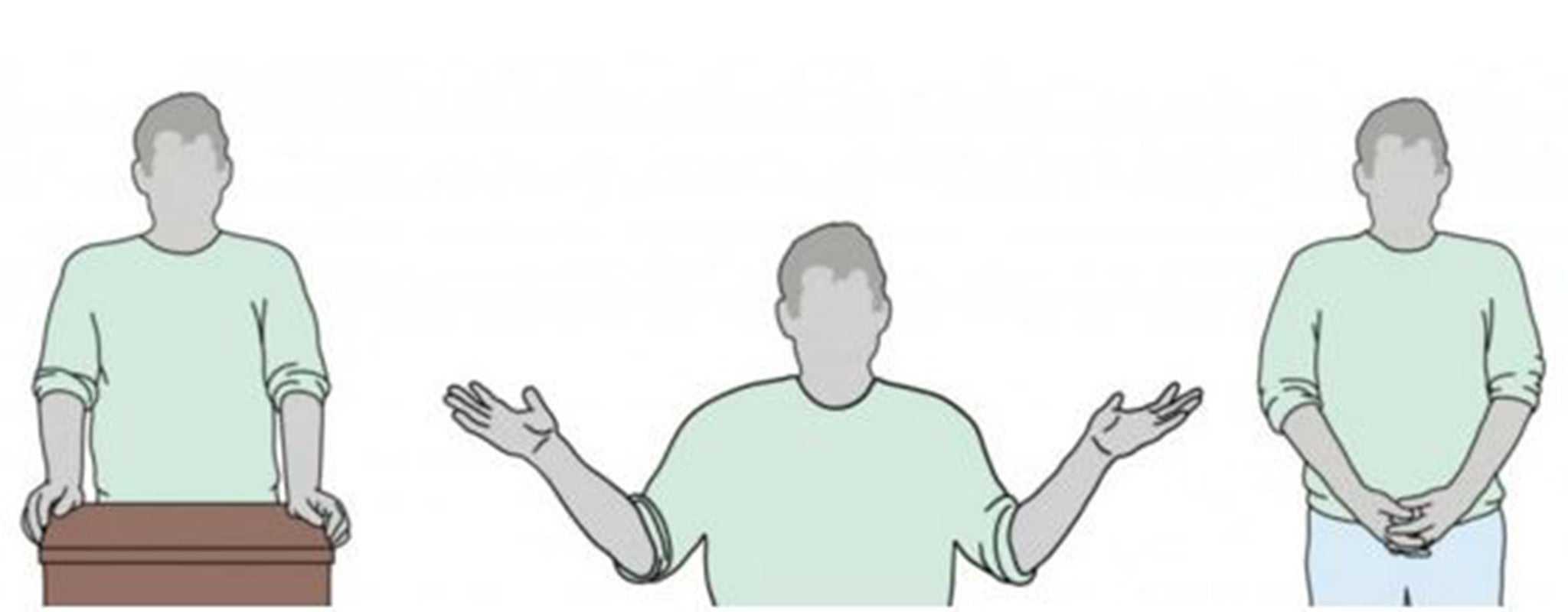

Standing behind a big furniture piece might make some people feel safer, but it causes problems for others. Gripping the top of the lectern, revealing white knuckles as you steady your nerves, or making low hidden gestures that can't be seen by the audience are all common blunders. Instead, hands "should be out and alive and moving and not holding on for dear life," Barnett says. Either rest them on the lectern lightly or use gestures the audience can see.

Hiding your hands isn't a good idea away from the podium, either. Van Edwards remembers one client who was seen as cold and intimidating by his team. After sitting in on a few meetings, she noticed he regularly held his hands behind his back while talking. "As soon as he pulled his hands out from behind his back, the amount of discussion and length of it increased two-fold," she recalls. "I can’t say it was only that, but it was the clearest moment where I was like 'wow, [showing our hands] really does something subconscious in our brains that helps us trust.' "

German Chancellor Angela Merkel has a trademark hand gesture, one so well known that it has inspired Internet memes and emoticons, has its own name ("Merkel-Raute") and has even been depicted on a giant political campaign billboard. She holds her hands in front of her midsection, fingertips and thumbs typically touching in a diamond shape with the fingers pointed down.

It may somehow work for Merkel as her signature gesture, but others should avoid it. Generally, touching the finger tips—what Barnett calls "spider hands"—can look tense and unrelaxed. A branded gesture like Merkel's can "feel sort of stagey," she says, and is distracting to the audience.

And then, of course, there's the risk of unintended meaning. Pointing the thumb and index fingers together in a diamond shape is similar to the sign language gesture for a part of the female anatomy. And that's exactly the kind of confusing signal no speaker wants to send.

Washinton Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments