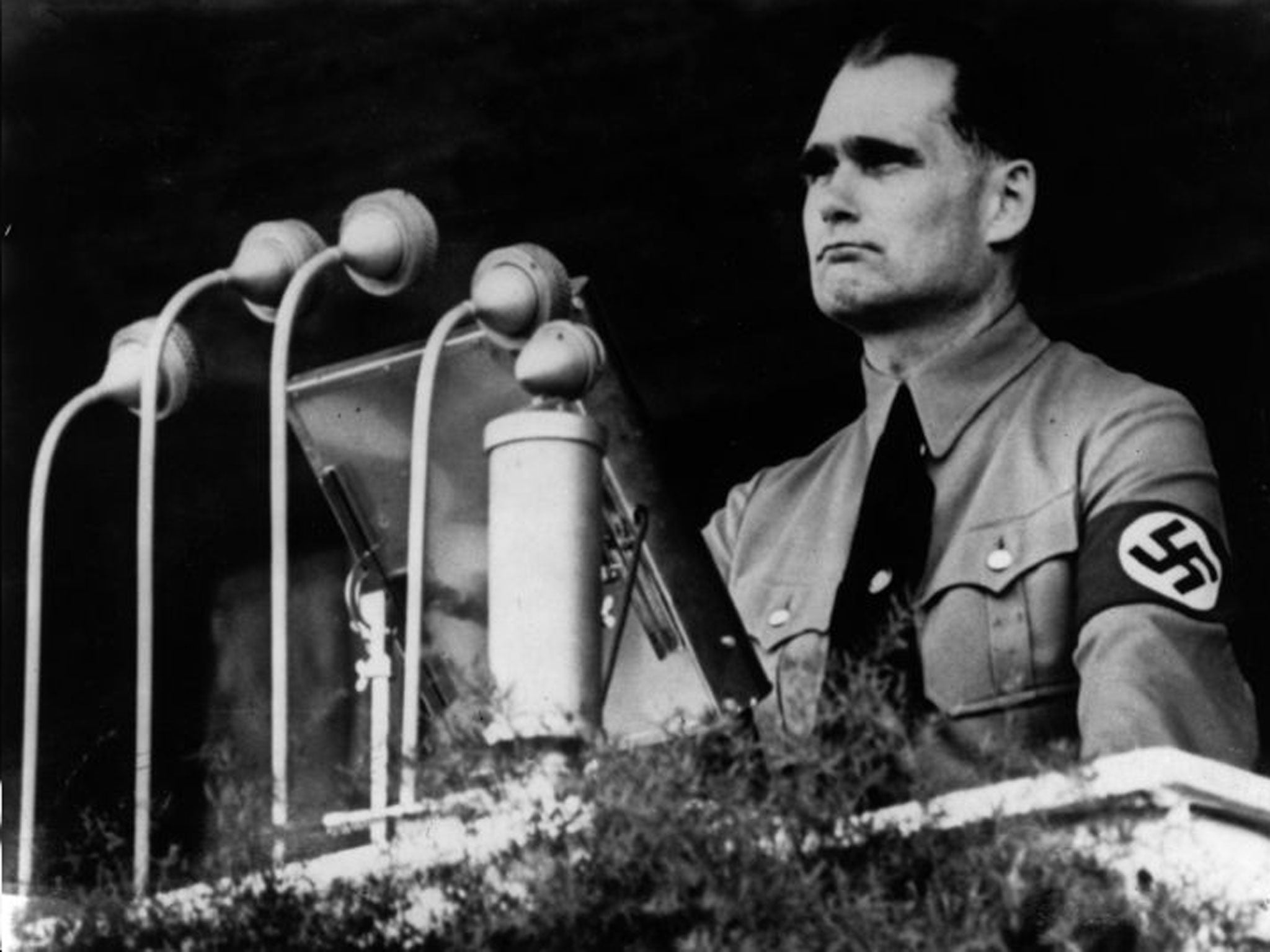

Revealed: The spymaster and Nazi peacemaker Rudolf Hess

Recently auctioned file belonging to Hitler’s deputy offer insight into more of his bizarre wartime plans

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When the bidding ended for lot 171 in a US auction room last week, the $130,000 (£82,000) offer was insufficient to secure its prize – a small, ripped, buff folder marked “Most Secret” with the word “Hess” faintly scrawled in pencil across the cover.

The failure to meet the $700,000 (£441,000) reserve price was shrugged off by the auctioneers in Chesapeake City, Maryland. After all, this was “perhaps the most important wartime archive ever to be offered for private sale”. The file contained 14 documents written by Adolf Hitler’s deputy führer, Rudolf Hess. Together, it is claimed, they offer a rare insight into the mindset and goals of the man behind one of the strangest and most perplexing episodes of the Second World War.

On 10 May 1941, while London endured one of the most devastating nights of the Blitz, Hess parachuted on to a Scottish field on a self-declared mission to negotiate peace with Britain. He failed, was captured, and later died, aged 93, as “Prisoner Seven” in Berlin’s Spandau prison.

How the file ended up on sale in the US is as mysterious as the saga of Prisoner Seven’s arrival in Britain. Hess experts told The Independent on Sunday that they believe the file was taken from the archives of MI6 by its former head, Sir Maurice Oldfield, prior to his death in 1981, to prevent its destruction by the UK authorities. Alexander Historical Auctions said that it acquired the papers from an unnamed European individual, and that it had received no approach from the British authorities to claim them.

Hugh Thomas, a former military surgeon who once treated Hess and is the author of two books exploring the theories that “Prisoner Seven” was an imposter planted by the Nazis, said that he had personally handled the file and was aware of its provenance. He said: “Sir Maurice removed the file without the intention of permanently depriving the government of it, because he was concerned it could be destroyed ... and the truth about Hess’s captivity concealed.”

Scott Newton, professor of modern British history at Cardiff University, said recently: “Like many historians, Sir Maurice believed the Hess affair still holds great secrets. Unusually, he had the chance to take action to stop the archives being ‘weeded’ before they were opened to historians.”

Among the documents is a letter sent by Hess to King George VI in 1942 asking for the appointment of a commission to investigate his treatment in captivity. In a separate document, drawn up by Hess after his meeting in May 1941 with the Duke of Hamilton, the Scottish aristocrat who he hoped would act as an intermediary with Winston Churchill, the deputy führer laid out what he saw as the desperation of Britain’s position in the war. “The British cannot continue the war without coming to terms with Germany. By my coming to England, the British government can now declare that they are able to have talks.”

The auction house owner Bill Panagopulos said that while the file did not make its reserve, he still expected to complete a sale. “We have much interest from potential buyers,” he said.

The Foreign Office said it was aware of the sale and it had no reason to believe the file had come from its own archive. A spokesman added: “We do not comment on matters concerning the Secret Intelligence Service.” The government’s own papers on Hess will remain closed until at least 2017.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments