Cracking the codex: Long lost Roman legal document discovered

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Dr Simon Corcoran and Dr Benet Salway of the history department at University College London have found fragments of an important Roman law code that previously had been thought lost forever.

It’s believed to be the only original evidence yet discovered of the Gregorian Codex – a collection of constitutions upon which a substantial part of most modern European civil law systems are built.

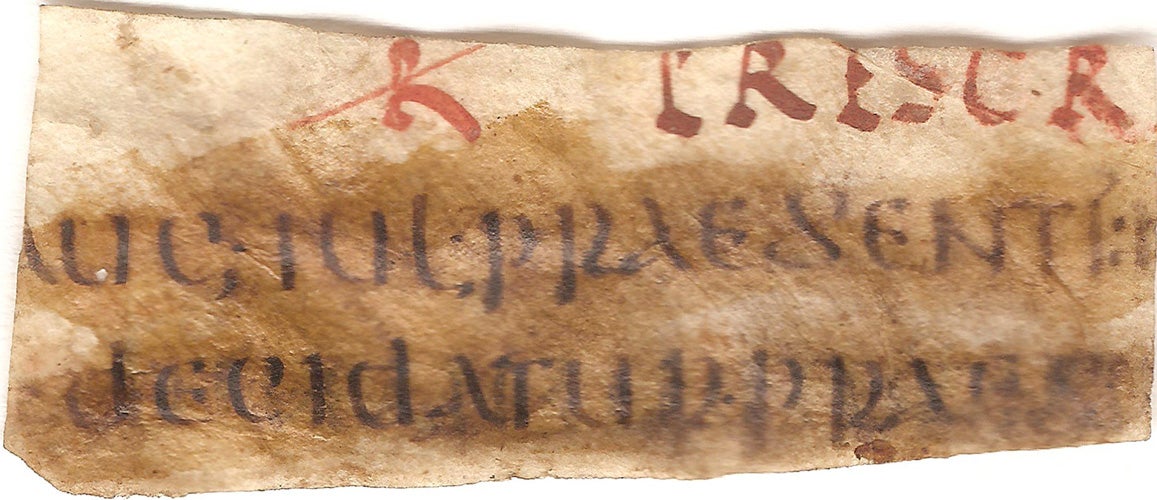

They made their remarkable find by painstakingly linking 17 pieces of seemingly incomprehensible parchment. Together they form, according to Dr Salway, “a page or pages from a late antique codex book – rather than a scroll or a lawyer’s loose-leaf notes,” judging by the number of abbreviations within characteristic of legal texts, and the presence of writing on both sides of the fragments.

Thought to originate from Constantinople (modern Istanbul) the page or pages bear “the text of a Latin work in a clear calligraphic script, perhaps dating as far back as AD 400,” Salway added.

Code breakers

The Gregorian Codex – or the Codex Gregorianus – was compiled during the reigns of a string of Roman emperors, from Hadrian (117-138 AD) to Diocletian (284-305 AD). It was thought to have been published around 300 AD, but little is known about its original format and composition. The identity of its author – a man by the name of Gregorius (or Gregorianus) – is very shady, and no surviving copies have been found. Until now, that is.

“These fragments are the first direct evidence of the original version of the Gregorian Code,” said Dr Corcoran. “Our preliminary study confirms that it was the pioneer of a long tradition that has extended down into the modern era and it is ultimately from the title of this work, and its companion volume the Codex Hermogenianus, that we use the term ‘code’ in the sense of ‘legal rulings’.”

Signs of “Intensive Use”

The fragments found by Corcoran and Salway contain sections where Roman emperors have replied to legal questions raised by members of the public. The pages have evidently been reviewed quite heavily, because various scribblings in have been added by readers around the main text. “The responses are arranged chronologically and grouped into thematic chapters under highlighted headings, with corrections and readers’ annotations between the lines,” commented Dr Salway. “The notes show that this particular copy received intensive use.”

There are passages within the script that are consistent with quotations of the code in other documents. Additionally, there are sections of new material never before seen in modern times that should make for fascinating and highly illuminating study.

Dr Corcoran and Dr Salway’s finds were made as part of Project Volterra – a ten year study of Roman law in its full social, legal and political context, funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council. It’s hoped that further examination of these Gregorian Codex fragments will yield some revealing insights into the late period Roman legal system.

Shooting Hadrian's Wall - Photography Tips From Derry Brabbs

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments