Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.World Health Organisation chief Margaret Chan on Thursday vowed to "change the landscape" for mental health, saying neglect is leaving millions of poor people without care.

About 75 percent of sufferers in poor and middle income countries are thought to be left untreated, a problem fuelled by a lack of knowledge among ordinary doctors and nurses, health experts sayd. Adding to the problem is social stigma, neglect, lack of funding, and an increasingly challenged rich country focus on psychiatric institutions.

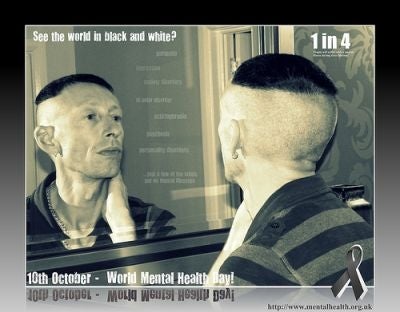

"One in four people are affected by mental, neurological disorders or substance abuse in their lifetime," said WHO Assistant Director General Ala Alwan.

The WHO estimates that 150 million people suffer from depression - 95 million of them in developing nations - 40 million from epilepsy, 20 million from dementia or Alzheimer's disease among a host of mental or neurological disorders.

"Efforts to close the mental health gap have been impeded by a widespead assumption that improvements in mental health require sophisticated and expensive technologies, delivered in highly specialised settings by highly specialised staff," said WHO Director General Chan.

"We face a misplaced perception that mental health intervention is a luxury," she added pledging to challenge that attitude.

While high profile diseases grab attention, mental and neurological disorders are "swept under the carpet and brushed aside" even though they form 14 percent of the global disease burden, said Chan.

A cornerstone of the drive is a new guide for ordinary doctors and nurses in developing and emerging countries to ease diagnosis and proper treatment of mental and neurological disorders, as well as drug and alcohol abuse.

Chan said it could "change the landscape for mental health."

Drawn up by 200 specialists from around the world, the guide places the emphasis on primary care, leading general doctors methodically through each stage from identifying symptoms of disorders such as depression and epilepsy to treatment or care.

But the experts discovered that 99 percent of the knowledge came from rich nations, and faced substantial work in adapting it to developing countries, said one of the authors, Graham Thornicroft of the Institute of Psychiatry in London.

The guide covers depression, psychosis, bipolar disorders, seizures, behavioural and developmental disorders, dementia, alcohol problems, drug addiction and suicide.

Its guidance take into account the needs of different genders as well as age - for example by avoiding drug treatment for children suffering from symptoms of depression.

"The programme will lead to nurses in Ethiopia recognizing people suffering with depression in their day to day work and providing psychosocial assistance," said WHO mental health director Shekhar Saxena.

"Similarly, doctors in Jordan and medical assistants in Nigeria will be able to treat children with epilepsy."

"Both these conditions are commonly encountered in primary care, but neither identified nor treated due to lack of knowledge and skills of the health care providers," he explained.

Saxena insisted that the experts had steered clear any commercial influence on their guidance.

"It's very easy to fall into the trap of recommending medicines," he added.

pac/cw

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments