Pad Man: How Bollywood is challenging period stigma in India

A new Bollywood movie, based on the story of an Indian entrepreneur who created affordable sanitary pads, is helping to counter myths and taboos around menstruation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

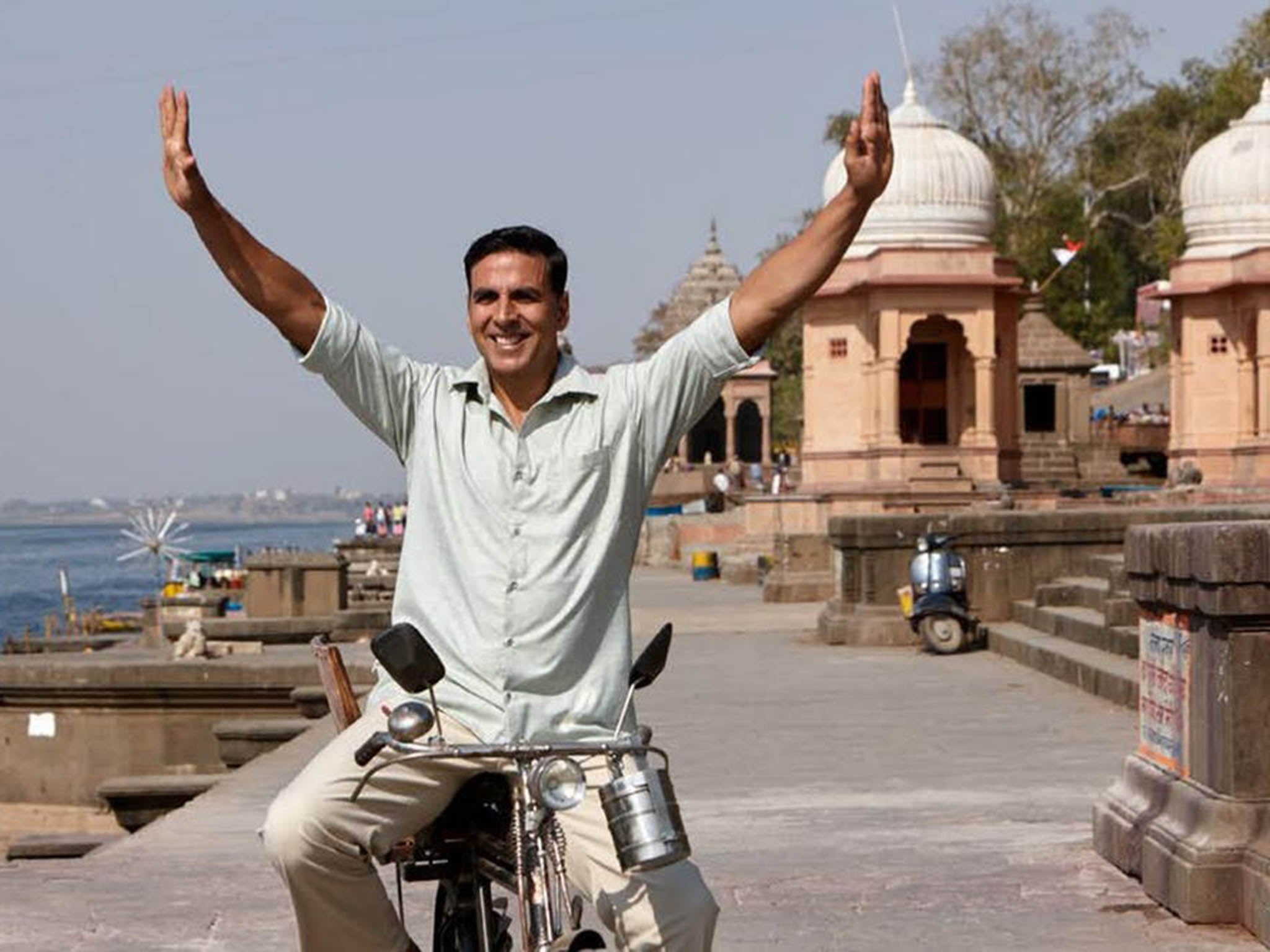

Your support makes all the difference.The new Bollywood film Pad Man, starring Akshay Kumar, is the story of how India’s “menstrual man” Arunachalam Muruganantham came up with a revolutionary new method of producing cost-effective sanitary pads. This helped to improve menstrual health and provide an income for rural women in India and beyond.

India is the leading film market in the world, with 2.2 billion tickets sold in 2016. One of the aims of this new comedy-drama is to reach a wide audience, create awareness and challenge the taboos and stigma surrounding menstruation in India.

It’s been more than 10 years since Muruganantham invented a machine to create low-cost sanitary pads and began distributing them to rural women across India. Traditionally, rural women use old cloth, saris or bed sheets as sanitary towels; sometimes also using sand, dirt or ash for heavy days. The use of pads is increasing and now six out of 10 women in India have access to disposable menstrual products.

This varies greatly across states – from as high as 90 per cent in Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Delhi to as low as 30 per cent in rural Bihar. But disposable pads are expensive and the biodegradable pads made by Muruganantham are cheaper and last longer.

Many non-governmental organisations around the globe, such as Days for Girls, focus on the need for hygienic menstrual products and make and distribute reusable pads. The argument is that the provision of pads enables girls to stay in school. One in four girls in India miss one day or more in school during menstruation.

Wider issues

But access to pads is only one issue. Girls might also miss school because of period pain, lack of toilet facilities, the fear of staining clothes or the views of teachers and family – last year, students were allegedly forced to strip in a school to see who was menstruating. This is not just an issue for India: one in 10 girls in some parts of sub-Saharan Africa miss school because of their periods and even in the UK period poverty causes similar issues.

The wider issue that Pad Man highlights is the stigma and taboos that surround menstruation. In India, restrictions include not being allowed to enter religious shrines, touch people or food in the kitchen, or touch or eat pickles. Taboos around periods exist in almost every country in the world, meaning many women and girls face discrimination. Global stigmas and practices include:

Nepal: Chaupadi is a social tradition associated with the menstrual taboo in western Nepal that forces women and girls to sleep outside their house, often in a cowshed, while they have their period. Chaupadi was banned in 2005 and made a criminal offence in 2017, but one young woman has already died in January 2018 because of it.

Japan: Women cannot be sushi chefs as menstruation affects their sense of taste. But women are fighting back and opening their own restaurants.

Afghanistan: Women are told washing or showering during their periods can lead to infertility.

Bolivia: Women are told putting used sanitary pads in the bin with other rubbish can lead to cancer.

US: 42 per cent of women have experienced period shaming, 58 per cent felt embarrassed and 73 per cent hide pads and tampons from view.

UK: 26 per cent of girls did not know what to do when they first started their period and 48 per cent are embarrassed by their period.

It’s interesting to note that the first major film to tackle this issue focuses on a male entrepreneur. Yet there are many other organisations and inspirational individuals, usually women, working to challenge the stigma around periods. For example in India, there is Aditi Gupta, founder of the Menstrupedia comic, which aims to educate children about menstruation. Writer and peace campaigner Radha Paudel is also challenging chaupadi in Nepal.

Education is key to changing attitudes to menstruation and in order to do this we need to engage men and boys. Perhaps male hero Pad Man is a first step.

Being able to manage menstruation safely and without stigma is a basic human right that many women and girls are denied. The silence and stigma around menstruation cannot be replaced by a new form of sanitary pad; it can however be challenged by discussion and awareness, and Pad Man can perhaps play an important role in starting the conversation.

Kay Standing is a reader in gender studies at Liverpool John Moores University. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments