How doctors decide if older patients can cope with an operation

In geriatrics, frail is not merely an adjective

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

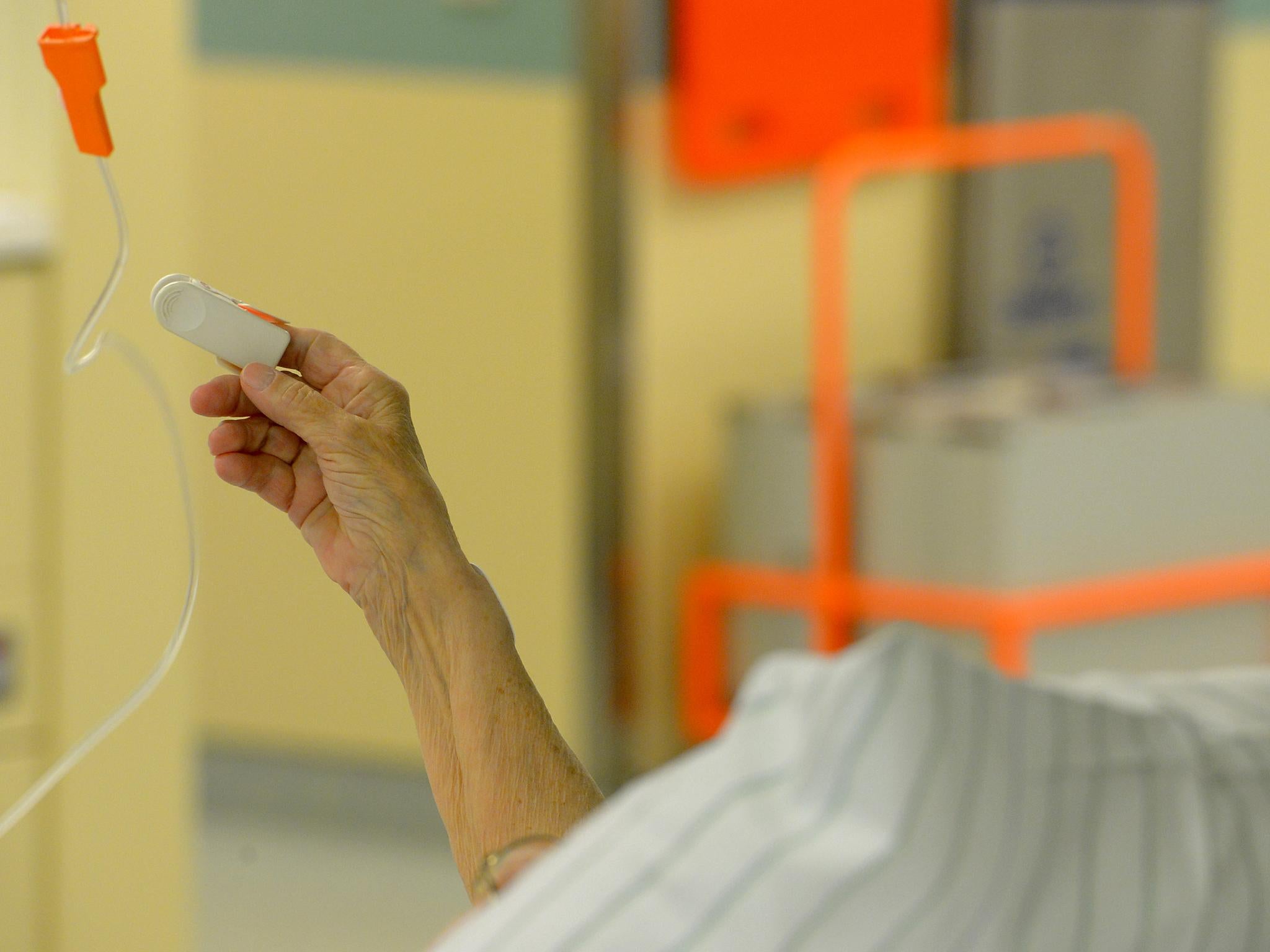

Your support makes all the difference.This month, Dr Thomas Robinson, a general surgeon at the Denver Veterans Affairs Medical Centre in the US state of Colorado, saw a patient in his mid 80s. The man had gallstones that caused infections, with abdominal pain severe enough to send him to an emergency room every couple of months.

The surgical solution to this problem is usually clear: remove the gallbladder with a procedure called a cholecystectomy. “In a 60-year-old, chances are it’s an outpatient operation,” Robinson says. In this case, though, he hesitated. Like a growing number of surgeons, he wanted to know, before presenting the options, whether or not his patient was frail.

In geriatrics, frail is not merely an adjective. A syndrome signified by slowness, weakness, fatigue and often weight loss, frailty tells doctors a lot about their patients’ likely futures. It can, for example, predict how well older patients rebound from physical stresses – such as surgery.

“Some 86-year-olds live independently and are really healthy, and we take out their gallbladders all the time,” Robinson tells me. But this patient, a nursing home resident who also had heart disease and pulmonary disease, scored moderately to highly frail on a commonly used index.

In particular, the man performed poorly in what’s called the “timed up-and-go”, which measures how long it takes someone to rise from a chair, walk 10 feet, turn around, walk back and sit down again.

Along with the other frailty measures, that means that “surgery is not going to go very well”, Robinson says. In a frank half-hour conversation, he explained to his patient that he faced a 30 percent to 40 percent risk of dying from the surgery. If he survived, he would probably endure a long, difficult recovery and might not regain the functional abilities he had now.

Dilemmas like these will grow more common as the population ages. Already, more than a third of inpatient surgical procedures are performed on patients older than 65. But about 15 percent of the older population, excluding nursing-home residents, meets the criteria for frailty, rising to more than a third of those older than 85. “There’s a much higher prevalence in the Deep South and among African-Americans,” says Dr Jeremy Walston, principal investigator at the Older Americans Independence Centre at research organisation Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Geriatricians like Walston have been publishing research on frailty for nearly 20 years, as measured by tools developed at Johns Hopkins, a separate Canadian version and variants thereof. The Hopkins approach uses tests such as grip strength and walking speed; the Canadian index relies on health deficits, including chronic illnesses and dementia.

Both assessments do a good job of identifying patients vulnerable to health problems, regardless of chronological age. A British group has used meta-analyses, for instance, to show that frail older adults are more prone to falls, fractures, hospitalisations, dementia and nursing-home placement.

In the United States, though, “it’s the surgeons who have picked up the banner”, Walston says. They’re starting to use frailty to help make decisions about which procedures make sense for which older patients. You can see why: frailty involves decreased physiological reserve, which helps determine how patients respond to physical stress.

Surgery brings plenty of that, says Dr Carolyn Seib, a general and endocrine surgeon at the University of California, San Francisco. The effects of anaesthesia and inflammation; the risk of blood clots or infection and muscle weakness caused by days in bed can all take a toll. “The more frail a patient is, the higher the risk of complications,” Seib says.

Researchers have shown that after major operations – including cardiac and colon cancer surgery and kidney transplants – frail older patients are more prone than others to longer hospital stays, being re-admitted within a month of a procedure and ending up in nursing homes after they’re discharged. They’re also more likely to die.

But a study that Seib and her colleagues published in JAMA Surgery this month shows that frail seniors face higher complications even after ambulatory surgery: outpatient procedures that often are considered routine. Hernia repairs, thyroid or parathyroid surgery, operations for breast cancer – “patients and providers often don’t think twice about these,” Seib says.

Yet when the researchers looked at 141,000 patients older than 40 in a national surgical database, they found that serious complications were two to four times higher in patients with moderate to high frailty, although complication rates overall were low (1.7 percent, with 0.7 percent experiencing serious complications).

“We have to take frailty into account for any operation, big or small,” Seib says. Although surgeons increasingly screen for frailty, “I wouldn’t say it’s routine yet”, she adds. So she and other researchers recommend that before an operation, patients and families ask: Is my mother showing signs of frailty? Should we do an assessment that indicates how frail she might be?

Unlike some conditions, frailty is something patients and doctors can actually do something about. “There are interventions that can improve or even resolve it,” said Dr Linda Fried, dean of the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University and a pioneer in frailty research.

Firstly, many surgical centres offer a “prehabilitation” programme, shown to improve patients’ results through exercise, better nutrition and smoking cessation. Undertaken even for a few weeks before an operation, “it improves your bounce-back capability”, Fried says. Physical activity, in particular, “seems to be the key to preventing frailty and its progression”, Fried adds – even for those not contemplating surgery.

Secondly, surgical decision-making is not a binary choice between patients agreeing to the standard operation or doing nothing. Alerted to frailty, a surgeon might opt for a less aggressive approach or a different kind of anaesthesia. A patient, understanding that they may be looking at an altered future even if the surgery fixes the physical problem, will have their own priorities to weigh.

With frailty, “I’m going to counsel the patient differently”, Robinson says. “Maybe change the surgery I do. Maybe find an alternative. There’s a spectrum of possibilities.”

Take, for example, his patient with gallstone disease. After their discussion, the man decided that instead of undergoing what would be, for him, a high-risk operation, he would go home and try to avoid foods that triggered his symptoms. If the pain flared again, Robinson would insert a tube through his skin to drain the gallbladder, a much safer procedure.

Because the tube, and the bag into which it drained, would be permanent, it might not represent a welcome alternative for a healthier patient. But “for a physiologically vulnerable older adult,” Robinson says, “it’s a whole different equation”.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments