Murder or infanticide? The causes behind the crime

The killing of a newborn baby by its mother is both shocking and rare - but more needs to be done to understand the mental condition of the women that commit it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

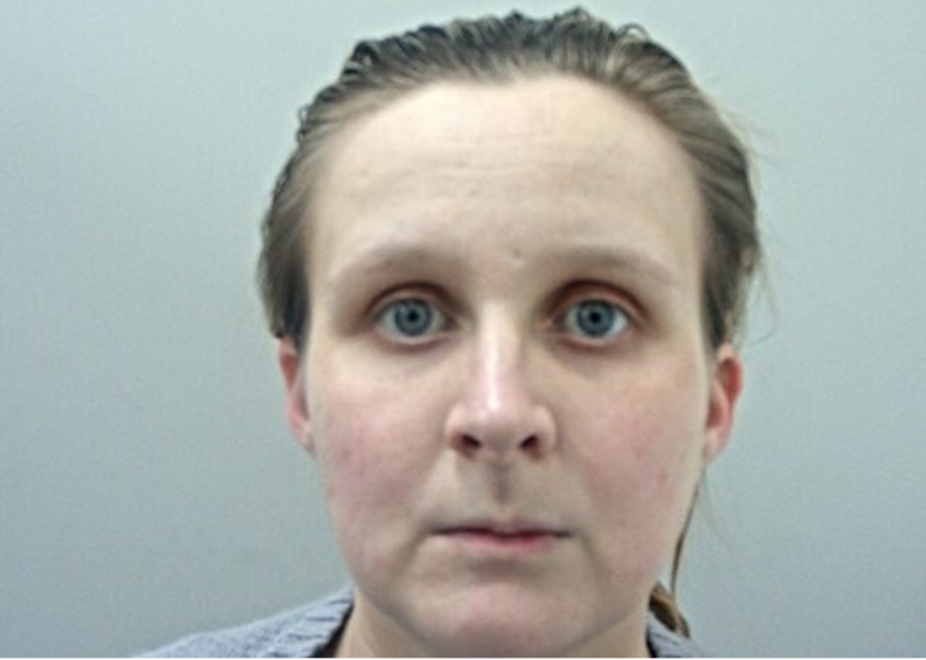

Your support makes all the difference.The murder of newborn baby Mia Kelly by her mother, Rachel Tunstill, was branded “horrific, callous and brutal” by police in Lancashire. Tunstill was sentenced to life imprisonment – with a minimum term of 20 years – after a jury found her guilty of murder.

The judge, Mr Justice Davis, said there was “no way of knowing” why this “dreadful crime” happened. But I believe the courts do not yet fully understand the mental trauma which, according to my research, appears in so many of these disturbing cases.

While no accurate figures exist as to the number of cases, from my research I estimate that in England and Wales around seven cases are investigated by the authorities each year – although very few result in homicide convictions.

Tunstill’s trial was told how her pregnancy ended with her delivering the baby on her own, into a toilet. She then asked her boyfriend, who was in the next room, to pass her a pair of scissors, which she then used to stab the child to death.

Neonaticide, the deliberate murder of a baby by its parent during first 24 hours following birth, is mostly committed by women following a pregnancy that has been concealed or denied from the wider world. Much of the research identifies the stereotypical neonaticidal woman as young, single and poor. They often lack the economic, social and emotional resources to deal with the pregnancy. Yet other research has shown that some women come from a range of demographics.

It is evident, from studies of the motivation of women who kill their newborn child, that they are vulnerable. Fear and shame of the pregnancy is common, as is the belief that the pregnancy cannot exist – which leads women to hide their condition from the world. Consequently, they are left with few choices but to give birth in secret, often in extreme panic.

What is unusual about Tunstill’s case is her conviction for murder, and the subsequent life sentence she received. From my research into cases of suspected neonaticide in England and Wales from 2010 to 2014, I have not found any woman imprisoned for killing their newborn child since at least 2002 (when my inquiry ends).

All cases of a similar nature to Tunstill’s have resulted in a conviction for infanticide – defined under English law as the deliberate murder of a child under 12 months by the parent: a legally distinct offence from murder – or manslaughter due to diminished responsibility, but each of these convictions have resulted in a community sentence or a hospital order.

An example of this is the case of Gintare Suminaite, who killed her daughter shortly after giving birth in the bathroom of her West Sussex home. Her baby was the result of a secret affair and she kept her pregnancy hidden, the Old Bailey heard.

Suminaite, of Bognor Regis, denied murder but admitted infanticide as she was mentally disturbed by giving birth. The judge said her circumstances were “tragic” and sentenced her to a 24-month community order.

It is beyond the scope of this article to examine why Tunstill convicted of murder, rather than infanticide or manslaughter. Nevertheless, it would seem her case holds similarities to those that have resulted in an infanticide conviction.

The 1922 Infanticide Act, which legally differentiates infanticide from manslaughter or murder, was introduced in recognition of the socioeconomic “stressors” that could lead unmarried women to kill their illegitimate newborn children out of the shame of being pregnant out of wedlock, and to offer leniency in such cases.

It provides a partial defence to murder, and as such the sentence that applies (like other partial defences to murder, such as diminished responsibility or suicide pact) is the same as for manslaughter. Contemporary use of the offence provides for lenient treatment for women who appear to have been suffering the mental disturbance that is widely associated with neonaticide.

Disturbance of mind

Previous studies into the mental condition of women who kill their newborn children have reported that such women respond not callously and purposefully for self-preservation, but out of fear associated with shame and guilt of being pregnant and concern about the reaction of parents, partners and others if the pregnancy is discovered.

Psychiatric interviews conducted with defendants in the US by Margaret Spinelli concluded that the women suffered dissociative psychosis and hallucinations and intermittent amnesia. The women then awoke to find a dead newborn child whose presence they could not explain.

Tunstill, while accepting that she must have killed the child, said she had no memory of her fatal act. The psychiatrist acting for her told the court that she was suffering an acute stress reaction, which came against a background of mental disorder, including depression and Asperger’s Syndrome. Such evidence would suggest that the mental requirements for the offence of infanticide had been met.

Women who commit neonaticide are, by the nature of the circumstances of the pregnancy and birth, vulnerable. I have previously argued that the courts need to better understand the social context of a woman’s life that leads her to conceal or deny a pregnancy.

It would appear from Tunstill’s sentencing that a much better contextual understanding of these cases is still required in court.

Emma Milne is a PhD candidate, Department of Sociology, University of Essex. This article was originally published on The Conversation (www.theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments