How we discovered that a common antibiotic may be able to treat post-traumatic stress disorder

PTSD can happen to anyone, but there may be new ways to work through it

Doxycycline is a cheap, widely available antibiotic. It is used to treat everything from acne to urinary tract infections. This humble little pill, we have now discovered, might also be useful for treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

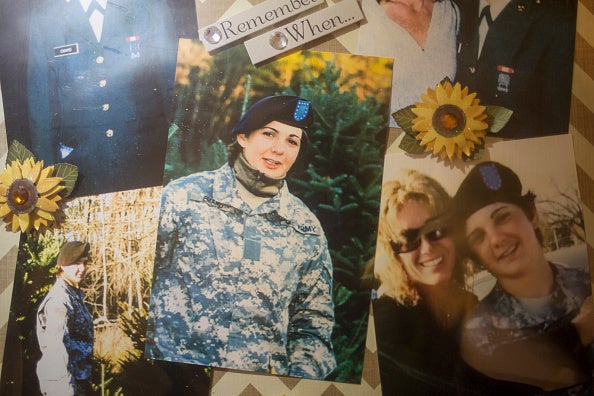

Many people associate PTSD with war veterans, but people can develop the disorder as a result of having experienced any type of extreme trauma, such as sexual abuse, a road traffic accident or a natural disaster. Not everyone who experiences trauma will develop PTSD, but those who do often experience hyper-vigilance, flashbacks and nightmares.

People diagnosed with PTSD are usually treated with talk therapy, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) or eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR). But talk therapy is expensive and time consuming, and it doesn’t work for everyone. If we could find a cheap, effective way to prevent or minimise the symptoms of PTSD, that would surely be a boon.

Hindering negative memories

Recent studies have found that, to form memories, our brains need proteins outside nerve cells, called matrix enzymes. Matrix enzymes are found throughout the body, and their over-activity is involved in certain immune diseases and cancers outside the brain. To treat these diseases, drugs have been developed that block these enzymes, including doxycycline. We wanted to know if doxycycline could be used to block the activity of matrix enzymes and hence prevent – or weaken – the formation of negative memories.

To test this theory, we recruited 76 healthy volunteers and randomly assigned them to either receive doxycycline (200mg) or a placebo. As the trial was “double blind”, neither the participants nor the investigators knew which pill the volunteers had received.

Having received a pill, the participants then took part in a computer test in which one screen colour was often followed by a mildly painful electric shock and another colour was not.

A week later, the participants returned to our lab. They were shown the colours again (40 times), this time followed by a loud sound but never by shocks. The loud sounds made people blink their eyes – a reflexive response to sudden threat. We then measured the activity of the ring muscle that closes the eye, to quantify the startle response.

Our analysis, published in Molecular Psychiatry, showed that those who were given a placebo had a stronger eye blink after the colour that predicted electric shock than after the other colour was shown. This “fear response” is a sensitive measure for the memory of negative associations, as has been demonstrated many times since it was first reported on in 1951. Strikingly, the fear response was 60 per cent lower in participants who were given doxycycline.

Dulling the fear response

Using drugs to prevent PTSD would, of course, be challenging: in the real world we rarely know precisely when a traumatic event will occur. But there is growing evidence that people’s memories and associations may be changed after the event. The idea is that when people actively imagine previous negative events, it makes their memory alterable. And for the memory to persist, it needs to be stabilised by a process called “reconsolidation”.

Certain drugs could potentially block reconsolidation, but many of these are not approved for human use. We are now going to test whether doxycycline will also block this reconsolidation process. If we are successful, the drug could be used to treat PTSD in a few years.

The idea is not to delete traumatic memories in the sense that people forget them entirely (learning to fear threats is an important ability that helps us avoid danger). To treat PTSD, it is important that traumatic memories stop scaring the patients, because the event has passed. This instinctive fear response is what doxycycline could potentially reduce.

At this stage, we don’t know why matrix enzymes are needed for memory. Nobel prize winner and biochemist Roger Tsien suggested in 2013 that memories aren’t stored in nerve cells (neurones) but in the scaffolding that surrounds these cells, part of the so-called extracellular matrix. While this theory is a great source of inspiration, we don’t yet have ways of definitively testing it. But even without answering this question, we are already in a position where approved drugs such as doxycycline may turn out to be helpful for treating PTSD.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments