Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In October 2004, Shaun Halfpenny, then headmaster of Cummersdale Primary School in Carlisle, had a bright idea. He was sick and tired of filling in the endless Health and Safety Executive (HSE) paperwork accompanying his pupils' field trips and wanted to take a pop at the quango's red tape. He assembled a group of schoolchildren, asked them to don some laboratory goggles, and got them to play conkers. He told the world's media that the goggles were a "sensible" step to protect children's eyes from pieces of flying chestnut.

Five years later the HSE is still trying to deal with the collateral knocks from Halfpenny's publicity stunt. In November 2004, The Cumberland News ran the story of conker-gate; it was picked up by the BBC News website, The Sun, and several other nationals. All of them spun it in the same way: that it was political correctness gone mad, that headteachers had to jump through so many hoops that Britain's traditional pursuits were in desperate peril (they declined to mention that Halfpenny was having a laugh at the system's expense and hadn't in reality instituted such a rule at his school). Sure enough, earlier this month, Conservative Party leader David Cameron was still lashing out at Britain's "stultifying blanket of bureaucracy, suspicion and fear", citing the conkers incident as an example.

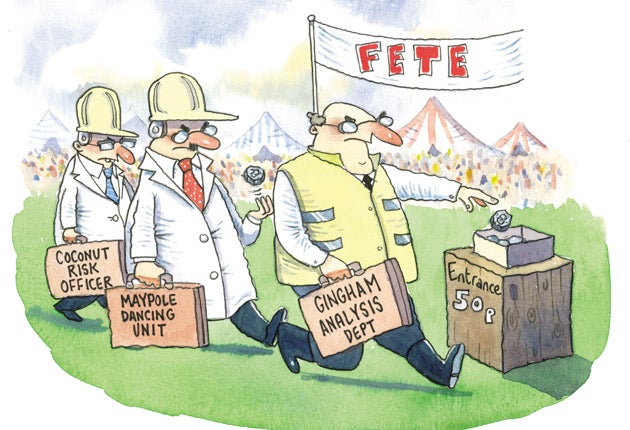

To coincide with the publication of the HSE's 2010 calendar of popular health myths (£5 from hse.gov.uk) – which includes classics like not being allowed to use toy weapons in theatrical productions, and the myth that if you call the HSE for advice you'll end up with an unwanted inspection – one academic has embarked on a quest to explain away health and safety myths for good. Paul Almond, a law lecturer at the University of Reading, has published The Dangers of Hanging Baskets – research discussing how health and safety myths, while amusing, are often singular events that are spun out of control by the media.

The media has always had a strange relationship with health and safety myths. On the one hand, they're quite amusing – there's a guaranteed top-line in lobbing a brickbat at others' stupidity, especially if it's the familiar local authority punchbag – on the other, if the myths persist, they become distorted and may mislead the public in the long term.

One of the most famous health and safety porkies is one that ran on the BBC News website in February 2004: it concerned Suffolk County Council's apparent banning of baskets of flowers hung from lamp-posts in Bury St Edmunds (Almond's report title refers to this). It was reported that members of the town council were incensed, accusing the county council of "guarding their own backs over health and safety". The academic says that various examples of the same distorted story have surfaced over the years: the most recent came up in the Daily Mail in April, on hanging baskets in Abergele, Wales.

"What happened in the Suffolk story was that the local council was concerned by how heavy these displays were when they were watered," explains Almond. "So the council took a few of them down, weighed them, and then returned them after they realised there wasn't a problem. In the long term it was revealed to be much more benign than the initial media firestorm might have us believe."

In these uncertain times, health and safety myths have an extended half-life. "A lot of them are explicitly political stories – these incidents are seen as a perversion of useful spending policies, and symbolise people's problem with central government over-investing in the nanny state," he continues. "On another level they tap into people's more generalised feelings of insecurity about the world changing around them. All of the examples of health and safety myths that I've collated concern some sort of impingement on British social traditions: cakes, pancake races, bonfires, graduates throwing mortar boards." The academic thinks that the demise of British manufacturing means that far fewer people work in situations – at foundries, for example, or using heavy machinery – where genuine health and safety rules might be useful.

Judith Hackitt, the HSE's chair, thinks that her organisation is an easy target. Hence the calendar, which runs through a series of myths and says that they're not all the HSE's fault really.

"If you want to make a ruling in the workplace, it's very easy to blame the HSE and no one will challenge it," she says. "It becomes an easy one for people to hide behind. All we want to do is alert people to the serious risks that there can be in the workplace – not all this trivia."

Almond thinks the HSE might be better off ignoring the myths. "If you give a rebuttal it sometimes gives extra legs to a story," he says. "It can often send things right back to the top of the news agenda. Maybe they should be hammering home the positive, rather than the frightening."

Rules that don't apply: The big myths

Health and safety regulations now ban the use of ladders

Explanation: "There are regulations aimed at ensuring people do use ladders safely," says the unnamed author of a 2006 TUC report on health and safety myths. "There is no ban on ladders."

Schoolchildren are not allowed to use cardboard egg boxes in craft lessons

Explanation: "This is probably related to a 2005 decision by East Sussex County Council to issue a circular indicating that there were in fact no problems in using both egg boxes and toilet rolls as long as they were clean," says the report. "This makes perfect sense."

Workplaces are "risk averse" and employers are overly cautious because of fear of health and safety regulations

Explanation: "The fact that over a million workers get injured every year and 25,000 people are forced to give up work because of injury or illness caused by work shows that employers are very much taking risks with their workers health," continues the report.

Firemen's poles have been banned on health and safety grounds

Explanation: "This seems to have arisen from a case in Devon in 2006 where it was reported that a new fire station had not been equipped with a traditional pole to avoid the risk of injury," states the report. "In fact it was because of space restrictions."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments