Zika virus: What is it and what are the symptoms?

Scientists warn that a new variant of the virus could be much more transmissible

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have found that a single mutation in the Zika virus could potentially trigger a new outbreak with far-reaching consequences.

The researchers, from the La Jolla Institute for Immunology in California, warned that the world should be on the lookout for new mutations of the virus, which is carried by mosquitoes.

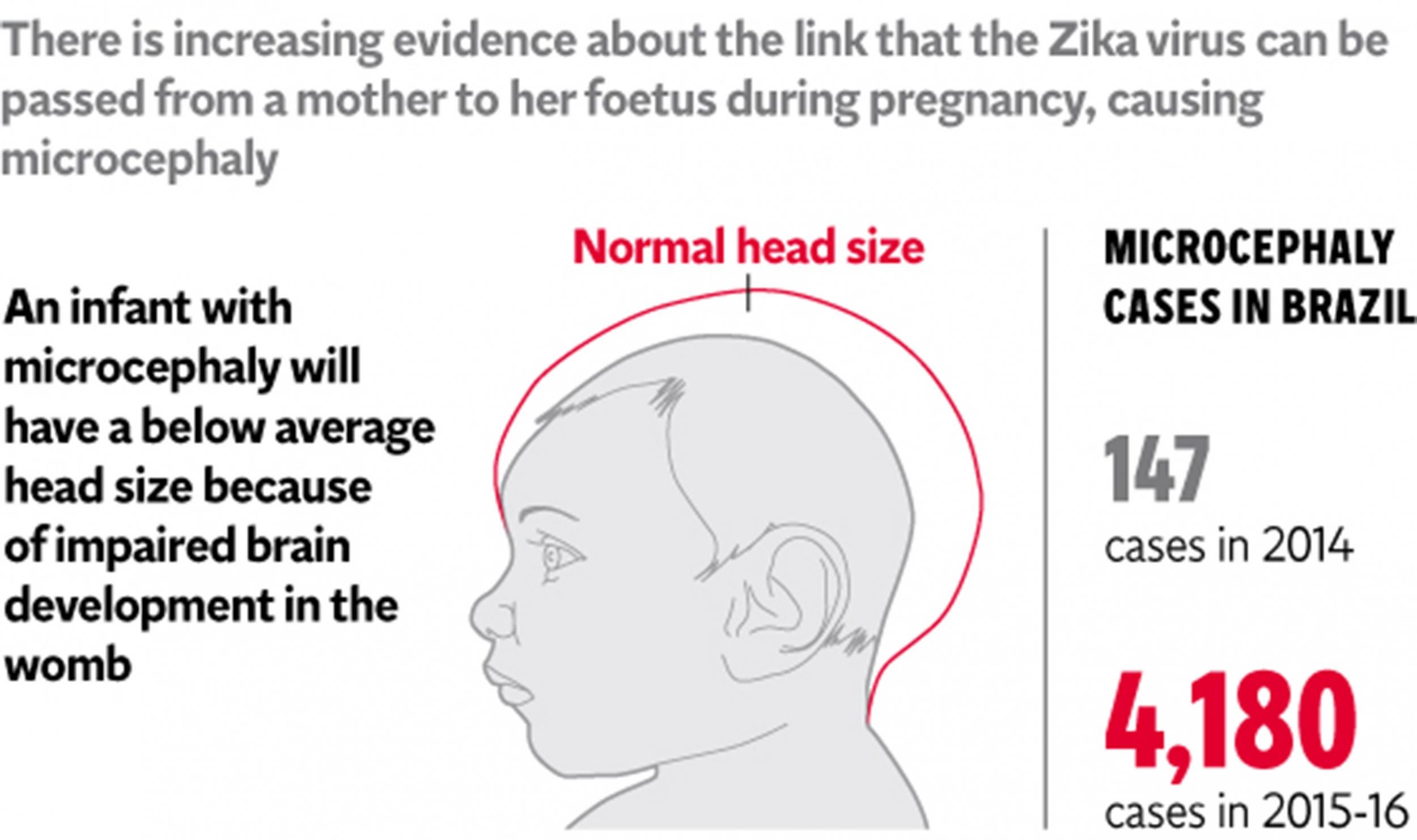

Zika virus infections are usually mild in adults, but it can result in birth defects such as microcephaly in babies when their mothers are infected while pregnant.

In 2016, the disease was declared a global public health emergency by the World Health Organisation as it swept through Brazil and the Americas.

By the end of that year, the emergency status was lifted, but more than 3,700 children were born with birth defects as a result of the disease.

Jose Angel Regla-Nava, the study’s first author, told Science Daily: “This single mutation is sufficient to enhance Zika virus virulence. A high replication rate in either a mosquito or human host could increase viral transmission or pathogenicity, and cause a new outbreak.”

If the Zika virus mutates and becomes more transmissible, what should we be worried about?

What is the Zika virus?

The Zika virus has been around for more than 60 years but it was only in 2016 that scientists and health experts became seriously worried about it.

The disease spread around the globe, but hit Brazil and the Americas the hardest.

Zika is a mosquito-borne disease that normally has symptoms similar to the dengue and chikungunya viruses, which are spread by the same genus of insect, the Aedes mosquito.

Named after the Zika Forest near Lake Victoria in Uganda, where it was first isolated in 1947 from a captive monkey, it has since spread across equatorial Africa and, more recently, to Asia, Pacific Polynesia and now South America, but only 14 “sporadic” human cases were detected until 2007.

That was when the first documented outbreak of the disease occurred on the Pacific island of Yap.

At that time, the virus was not considered to be dangerous as only mild symptoms were recorded and there was no link made to birth defects or microcephaly.

Another outbreak in French Polynesia in 2013 also caused little concern but transmission that started in Brazil in 2015, as well as in Cape Verde, was linked to brain damage to foetuses that can cause lifelong cognitive and health problems.

Should we be worried about it?

Initially regarded as localised and relatively harmless, a massive outbreak that started in Brazil brought it sharply into focus because of the disease’s links to microcephaly - a congenital disorder that can shrink unborn babies' brains and heads and reduce life expectancy.

At the time of the global outbreak, Zika appeared in at least 30 countries across the Americas, Pacific Islands and Cape Verde, as well as in Australia, Ireland and several other European countries where tourists were infected abroad.

The number of reported Zika virus cases began to decline in 2017, and there have been no reports of infections via mosquitoes in the US since 2018. According to Dr Lyle Peterson, director of the Centre for Disease Control (CDC) Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, Zika transmisison in the Western hemisphere is now “very, very low”.

However, he warned: “That doesn’t mean it’s gone away completely or that we won’t have to worry about it in the future.”

There is no known cure or vaccine.

The lead investigator of the new study, published in the journal Cell Reports, warned that scientists identified a variant of Zika that “had evolved to the point where the cross-protective immunity afforded by prior dengue infection was no longer effective in mice”.

“Unfortunately for us, if this variant becomes prevalent, we may have the same issues in real life,” Professor Sujan Shresta said.

Dr Clare Taylor, from the Society for Applied Microbiology, told the BBC: “Although these findings were seen in laboratory experiments and therefore have limitations, it does show that there is potential for variants of concern to arise during the normal Zika transmission cycle and reminds us that monitoring is important to follow viruses as they evolve.”

Is Zika dangerous?

The virus is not considered dangerous to anyone apart from pregnant women.

Most of those affected experience no symptoms, but about one in five people infected may experience fever, a rash, muscle and joint pain, conjunctivitis and fatigue around three to 12 days after being bitten.

The illness normally lasts from two days up to a week.

There are no Aedes mosquitoes, which spread the Zika virus, in the UK. Almost all cases that are found in the UK are associated with travel to countries or areas with active Zika virus transmission.

What are the symptoms?

Most people experience few or no symptoms if they become infected. If you do have symptoms, they are usually mild and last around two days to a week.

The most common symptoms include a high temperature, a headache, sore and red eyes, swollen joints and muscle pain, and an itchy rash all over the body.

How are pregnant women at risk?

According to the NHS, Zika virus can harm a developing baby if you become infected while pregnant, and can lead to problems with the baby’s brain and microcephaly.

However, it is possible to have the virus without experiencing any symptoms. The health service urges anyone who has just returned to the UK from a country where there is a Zika virus risk to avoid getting pregnant for up to three months afterwards.

You can speak to your midwife or doctor for advice if you are worried your unborn baby may be affected by the virus.

There is growing evidence of a causal link between Zika virus infection in pregnancy and births of a congenital disorder called microcephaly, where the brain of the developing foetus fails to grow normally and babies are born seriously deformed.

How is Zika virus treated?

The symptoms of Zika can be treated with common pain and fever medicines, rest and plenty of water, but anyone with worsening symptoms should seek medical advice.

How can you avoid getting Zika?

Current health advice suggests the best method of prevention to be avoiding mosquitos and their breeding sites, which can be in anything from large lakes, rivers and swamps to buckets of water.

People in areas of transmission are advised to wear insect repellent and light clothing that covers as much of the body as possible, hang mosquito screens and nets, and keep doors and windows closed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments