Why being funny is no joke

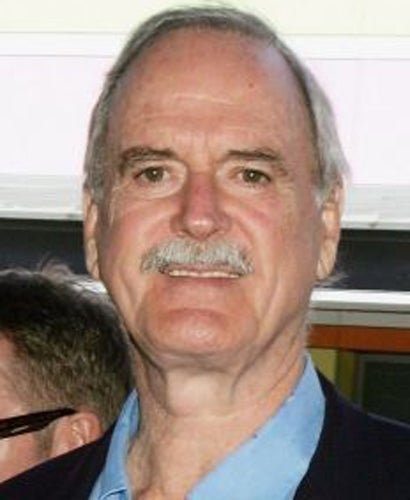

As a 'melancholy' John Cleese's third marriage comes to an end, Oliver James wonders what is it about comic geniuses that seems to make it so hard for them to be happy?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The demise of John Cleese's third marriage is particularly sad because he is one of our nation's best-loved public figures. The news leads, inevitably, to reflections on the price that many great comedians seem to pay for the joy and amusement they accord us.

Most – but not all – are either depressive or suffer from personality disorders (such as febrile emotions, "me, me, me" narcissism or omnipotence). Of course that does not, in itself, explain why they are so funny – millions of people have those problems and do not invent Basil Fawlty or create Blackadder.

Using pathology to explain art entails oversimplified reductionism of the most intellectually vulgar kind. But, having done in-depth TV interviews with seven leading comics and having met many others, I feel that it must be acknowledged that misery is a necessary condition for great humour in the vast majority of cases.

Cleese once took me out to lunch in 1983. Within a minute of sitting down at the table he asked me the question "do you think that anything at all is definitely true?" He was tenaciously serious, not in a tedious or earnest manner, but just chasing the truth at all times.

Unbelievably, during lunch, a portly German came up to our table and said "You have given my wife and I enormous pleasure". Cleese thanked him sincerely.

Instead of complimenting the erstwhile Basil Fawlty on not mentioning the war – clearly he would not warm to anything remotely friviolous – I commented how strange it was that people felt justified in coming up to famous people and how irksome it must be. Cleese replied: "No, I am very pleased to think that this man feels that I have given him and his wife pleasure".

That was the only time I met Cleese but he did provide a possible clue to the relationship between his melancholic tendencies and his comic genius. He said that if it was true that his work was in any way out of the ordinary, it was because he was a perfectionist. Long after the other Pythons had headed off to the pub, he would still be trying to make a script funnier.

There is such a thing as a healthy perfectionist. They derive pleasure from painstaking effort, strive to excel but are also able to tolerate limitations on what is possible. An example is our greatest ever comedy producer, John Lloyd, who made Hitchhikers Guide To The Galaxy for radio, and then for TV, Not The Nine O'Clock News, Spitting Image and Blackadder. Having achieved these remarkable successes, he felt able to retire from comedy production (his only TV since Blackadder has been the game show, Qi).

But most perfectionists are not like Lloyd, who I used to know in the 1980s. They tend to be hugely self-critical, or fearful of criticism from others, or prone to demanding absurdly high standards from those around them, or a mixture of all those.

A famous example, who I interviewed in 1987 was Ben Elton, co-author of Blackadder and much-lauded as a political comedian in the 1980s. I would say that, unlike nearly all the other comic performers I met in this context, he was neither severely depressed nor personality disordered. He had some signs of mild depression and was clearly quite obsessive in his thinking – linked to his perfectionism – and was, at that time, a workaholic.

But he was very much the exception. Much commoner was to have had highly critical, insatiably demanding parents, a classic prescription for depression. Adults who suffer from it are more likely as children to have been subjected to a torrent of negative, words such as "bad", "stupid", "inadequate", "useless", "unwanted". At least one in 10 of all children are exposed to such hypercritism. One was Stephen Fry.

A lifelong depressive, Fry used success as a buffer against a nagging, irrational self-hatred, explaining that "my achievements have been driven by a fear of inadequacy and unpopularity". He has terrible self-loathing: "As an adolescent, I was shy and awkward. I had an appalling body image, thought of myself as a quite revolting specimen and still do to some extent. I don't think of myself as an oil painting – oil slick would be closer. The fact that I don't inflict myself on women is the greatest favour I can do them."

The principal cause of that low self-esteem appears to have been his father. A scientist and businessman, Alan Fry had a brilliant mind and used it to find fault with his son. Says Fry of his relationship with his father, "There was a lot of tension and rivalry. He knew I was bright and therefore he was very irritated. He scared the living daylights out of me until I was 20".

His father was hypercritical: "He frowned at anything I did with any degree of competence." That attitude was still detectable in comments Alan made about his son in 1991. Said Alan, "I sometimes feel like saying to him 'stop doing this pappy and ephemeral stuff on the box and get down to some serious writing'. Stephen spends a lot of energy doing things that aren't worthy of him."

Hypercriticism was also there in Ruby Wax's childhood. As she has so vividly portrayed, her mother suffered from Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. She would torment Wax with a persistence and tyrannical detail that was enough to drive anyone crazy. Instead, Wax turned it into manic humour.

Other interviewees had suffered other kinds of fierceness. Julian Clary (who I interviewed in 1996) had been tormented by threats of hellfire from monks at his Roman Catholic school in Ealing, West London. Like Cleese, Clary seemed to me to make no attempt at all to "entertain" when off-screen. I found him a gentle, decent man, totally without narcissism, whose lugubrious temperament was darkened by the personal tragedy of a lover's death from Aids.

The maltreatment of Robbie Coltrane was from his father who beat him from a young age. That ended at the age of 15 when the not unbulky Coltrane fought back – his dad thought twice about using his fists on his son after that. Coltrane struck me as an idealistic person but with a sharply melancholic streak.

Two comics I interviewed who were never maltreated, and neither of whom were either depressive or personality disordered, were Julie Walters and Tracy Ullman. Both had lost their fathers at a young age and believed that their humour had developed as a way of cheering up their mums.

Interestingly, in all the fields where the matter has been investigated, one in three exceptional achievers lost a parent before the age of 14 (prime ministers, presidents, almost any dictator you can name, entrepreneurs, writers, poets – this 33 per cent compares with 8 per cent of people since the introduction of modern medicine, and 18 per cent before it). Indeed, there seems little doubt that childhood adversity and resultant adult pathology is almost mandatory in order for someone to become a genius, and especially so with comedians – think of the suicides, such as Tony Hancock (and, possibly, Kenneth Williams), the drunks, such as Peter Cook and Barry Humphries, or the schizoids (people with a weak sense of self and multiple personalities), such as Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan.

And yet, and yet ... millions suffer these adversities and have these problems without making anyone laugh. And how come some turn into the famously circumspect and pessimistic Rowan Atkinson whereas others become Winston Churchill?

Genes might be the answer, in theory. In fact, there is no evidence that they are and plenty of reason to doubt it. Humans are born enormously plastic, beyond the fundamental genetic repertoire of emotional potentials shared by almost everyone – like aggression, sexual desire, sociability and playfulness.

In order to thrive, it would make sense that we are not too specifically programmed in advance, because each of us needs to carve out a niche for ourselves in our particular family drama, need to develop the right character to attract parental interest.

When you get into the detail of comedians' lives it soon becomes obvious that they used humour as a way of thriving in their childhood environment. Genes could still explain why some are geniuses and others are Terry Wogan. But even that I doubt.

The most recent evidence from the Human Genome Project has forced molecular geneticists and psychiatrists to admit that there are no single genes for mental illnesses. Their fallback position is that it is a complex interaction of many different genes, although the evidence does not yet give them much support. Nor do I believe it ever will.

Early nurture and social processes are far more important – how else can you explain the fact that one quarter of citizens of English-speaking nations suffer mental illnesses whereas half that proportion do so in mainland Western Europe?

I predict that when we have a full understanding of the human genome, it will emerge that, just as with mental illness, genius of almost every kind is largely unaffected by genetic inheritance.

Oliver James is the author of 'The Selfish Capitalist – Origins of Affluenza'. His book 'Affluenza' – How to be successful and stay sane is out in paperback. James will be discussing 'Selfish Capitalism' with Will Self, Madeleine Bunting and Stewart Wallis in three London seminars in January – see www.selfishcapitalist.com.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments