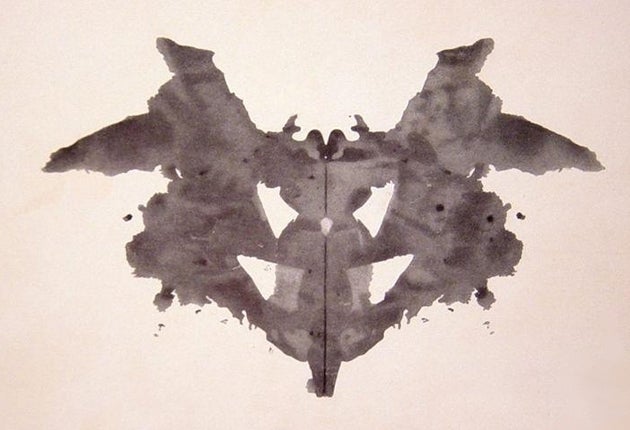

What do you see here? (the answer could say a lot about you)

For decades, the Rorschach test has been used to decode the human mind. But now the secret's out – and psychologists are hopping mad.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.To me it looks like a pair of pirouetting wolves. Others in the Independent office suggested a butterfly and one forensically inclined colleague thought it was a pelvis. Whatever you see, it could just open a window on your soul.

For decades, psychologists have used the Rorschach ink blot test to provide them with an idea of the sort of person you are. They show you a random pattern – the ink blot – ask you what you see and record your response. From that, the theory goes, they can construct a picture of how your mind works, and what may be wrong with it.

Now a Canadian doctor has spoilt the fun by posting on Wikipedia the 10 ink blot images used by Herman Rorschach, the Swiss psychiatrist who developed the test in 1921. And, in a move that has angered psychologists even more, he has posted alongside the images the commonest responses they evoke. Critics have besieged Wikipedia protesting that this is tantamount to publishing the answers to exam questions before anyone has sat the exam. It risks invalidating one of the oldest psychological tests in use.

The test is based on 10 standard ink blots created by dropping a blob of ink on a sheet of paper, folding it over and opening it up to create a symmetrical image. Of the 10 blots used, some are black and white, some red and white and some multicoloured. The subject is shown the images and invited to say the first thing that comes into their head about what they suggest. Later, the psychologist takes them back over the images, inviting them to say why they responded in the way they did.

Tony Black, a psychologist who has used the test, said: "It tells you something about how people respond emotionally. The images are composed of two symmetrical halves, so people often say they see a moth or butterfly with its wings. But then you get those who pick out a little area or feature and tell you a great deal about it.

"Depending on whether they expand and give a variety of responses based on the shape and the colour, or whether they stick rigidly to the whole image, you can get a broad idea about them. You can see what use they make of their imagination, how they see the world around them and what importance they attach to what they see. You can tell something about their initiative and ingenuity based on how they expand on different parts of the blot, or whether they stick to the whole thing."

Ersatz versions of the Rorschach test are available online for party games but Mr Black said the genuine test was always administered in person by the psychologist, so they can observe how the subject responds and explore the reasons with them. "There are quite marked differences in whether people respond to the colour or the shape," he added. "If someone says they see blood, it is obviously colour, because blood has no shape. If they say bats or butterflies, it is shape."

He was taught the technique as a trainee psychologist in the late 1950s in Liverpool and later used it on patients at Broadmoor high security mental hospital, where he was the first head of psychological services. "We were looking after some of the most violent people in the country, and it seemd to me important that we used the test to see what response we got," he said. "But I found the tendency of the Broadmoor patients was either to lay it on with a trowel and try to shock you, or to clam up and give you a minimal response or nothing at all. The results were not very helpful."

Today, he is sceptical of the value of the test, which takes time to administer and yields few insights that cannot be obtained more simply from modern personality questionnaires and interview techniques. "Some may find it a useful adjunct to help people open up in a psychoanalytic session but in general it has fallen out of use as a mainstream psychological method," added Mr Black. "However, I would be the first to say that so long as it is used as an assessment tool by many in the profession, it is quite wrong to leak it to a public medium. I disapprove of giving out details of the test.

"If it were to happen here I believe it would lead to a disciplinary charge. The British Psychological Society would haul you over the coals." The row kicked off in earnest in June following a simmering debate about Wikipedia's decision to post a single ink blot from the standard set of 10 on its site. James Heilman, an accident and emergency doctor from Moose Jaw, in Canada's Saskatchewan province, responded to the debate by posting all 10 images at the bottom of the article about the test, along with what research had found to be the most popular responses for each.

Explaining his provocative move, he told The New York Times: "I just wanted to raise the bar – whether one should keep a single image on Wikipedia seemed absurd to me, so I put all 10 up. The debate has exploded from there."

The 10 images have previously appeared on other websites but it was because they were being publicised by the highly popular Wikipedia that psychologists became concerned. Bruce Smith, the president of the International Society of the Rorschach and Projective Methods, said: "The more test materials are promulgated widely, the more possibility there is to game it ... rendering the results meaningless."

Dr Heilman was unrepentant. He said the dispute was about control and compared calls for the ink blots be removed to the Chinese government's attempt to control information about the Tiananmen Sqaure massacre. "Restricting information for theoretical concerns is not what we are here to do," he insisted. He pointed out that the standard Snellen chart used for eye tests, which begins with a big letter "E", is readily available on Wikipedia and no one complains about that.

"If someone had previous knowledge of the eye chart you could go to the car [insurance] people, and you could recount the chart from memory. You could get into an accident. Should we take it down from Wikipedia? My dad fooled the doctor that way."

The Wikipedia website says that outlines of the 10 official ink blots were first made publicly available in the 1983 book Big Secrets by William Poundstone. "They have been in the public domain in Hermann Rorschach's native Switzerland since at least 1992 (70 years after his death), according to Swiss copyright law. They are also in the public domain under US copyright law, based on when they were first created and published (before 1923).

"It has been claimed that publication of the ink blots has rendered the test meaningless. It is unknown how easily someone might study the ink blots and fool a psychologist into giving a wrong diagnosis."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments