The Big Question: Are we exaggerating the problem of obesity among Britain's children?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

Children are getting fatter, like their parents. Some people think the problem is now so serious that radical action is needed. Tam Fry, a spokesman for the National Obesity Forum, has called for the fattest children – the morbidly obese – to be taken into care. His proposal was backed by a third of the experts who attended a meeting of the forum in London, although he lost the vote on the debate.

Should fat children be removed from their families?

Malnourishment is treated as a form of child abuse and action is taken to protect the child. So should we not do the same with over nourishment? Mr Fry said yesterday: "I am talking about children who are so dangerously overweight that they are at risk from other illnesses such as diabetes. If they don't slim down they will run serious medical risks.

"There should be a case for them being removed from their parents to somewhere such as a paediatric ward where doctors could keep tight control of their eating. I am not saying keep them in total isolation from their families – parents should have access to maintain their link with the child which is vital. But removal is exactly what we would do in a case of malnourishment. It is just that over-nourishment is a new problem. People have not got their heads round it yet."

Are children already in care because of obesity?

Yes, according to Mr Fry, who said that Portsmouth was the first large British city to recognise obesity as a child protection issue and was drawing up guidelines for dealing with it. Last year, social workers in Wallsend, North Tyneside, considered taking Connor McCreadie, a boy of eight who weighed 13 stone, into care to help him curb his appetite. The plan provoked an outcry and the social workers instead agreed a contract with his mother and grandmother to control what he ate. But in Tower Hamlets, Lincolnshire and Cumbria, children who were excessively overweight had been removed from their parents, Mr Fry reported.

Can this be true?

Not according to the Association of Directors of Children's Services. A spokeswoman said: "A child would never be taken into care on the sole basis of obesity. That would never be the determining factor. However, it could be one factor in a judgement about neglect." Asked if overnourishment should not trigger the same intervention as malnourishment, she added: "Malnourishment has an immediate impact on a child's health and wellbeing and their ability to take part in a normal life. With obesity the direct link is less clear. It is also about intention – the question is whether people who overfeed their children are intentionally neglectful." Obesity was an issue of national importance and social workers were debating whether a new approach to managing it was needed, she said.

Are there other measures that could be taken?

Yes, though it is not yet clear what these might be. In a report this week, the Local Government Association, representing more than 400 councils in England and Wales, warned that Britain was becoming the "obesity capital of the world". Furniture in school classes, gyms and canteens is being made wider to accommodate larger bottoms and council play equipment is being modified.

David Rogers, the association's public health spokesman, said: "Councils are increasingly having to take action where parents are putting children's health in real danger. As the obesity epidemic grows, these tricky cases will keep on cropping up."

It was right that authorities should step in if "parents consistently place their children at risk through bad diet and lack of exercise", he added.

Can children be made to slim?

Yes, but it is a question of using a carrot-and-stick approach. Many of those who object to the idea of removing children from their families because they are obese support some form of intervention to encourage them to lose weight. This could involve regular visits from health and social workers to monitor the child's eating patterns and to help the family with buying and preparing food, as well as offering help with parenting problems. Targets for weight-loss could be set and rewards offered.

In extreme cases, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) has recommended that obese children might be considered for surgery to reduce the size of their stomachs.

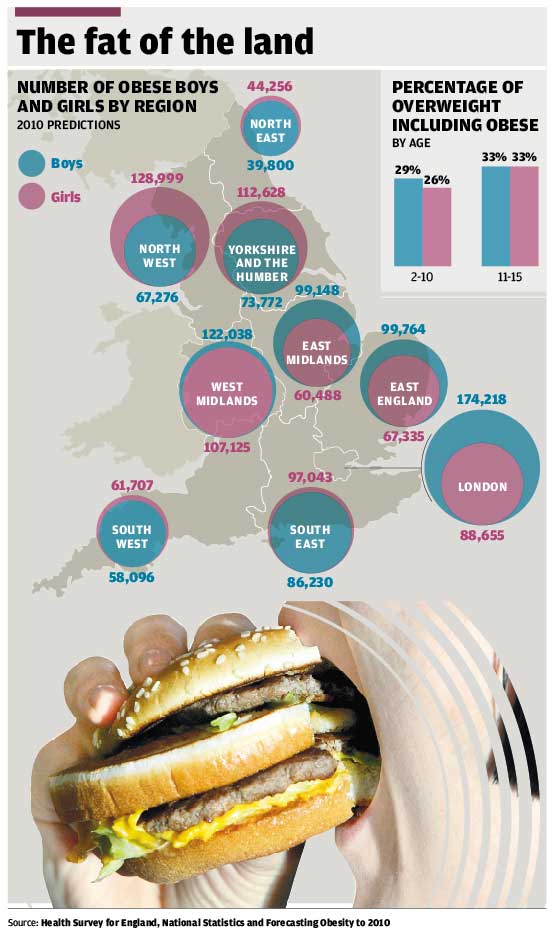

How bad is the problem?

The Government's chief medical officer, Sir Liam Donaldson, says that roughly two-thirds of adults and one-third of children are overweight or obese. Fat children tend to grow into fat adults, so it is important to nip the problem in the bud. If nothing is done, the cost to the NHS is expected to soar to £6.5bn by 2015. Ambulances are already having to be re-equipped with extra-wide stretchers, mortuaries are ordering bigger fridges and crematoria are having to enlarge their furnaces. Sir Liam says nothing has altered his view, first expressed five years ago, that obesity is one of the most serious health problems that Britain faces. But parents often do not recognise that their offspring are overweight. A recent survey showed that only 12 per cent of those with fat children knew their child was heavier than they ought to be. Fewer than four in 10 were aware that obesity can lead to heart disease and fewer than one in 10 knew of a link with cancer.

Is awareness of the problem improving?

No. The increased prevalence ofobesity among the population has changed what is perceived to be "normal" weight. This means that large numbers of people are underestimating how fat they really are. Recognising that you, or your children, are overweight is the first step to doing something about it.

What can parents do about it?

Many parents mistake overfeeding for love. As Miriam Stoppard, the doctor and television presenter, has observed, they give chocolates and chips as pacifiers instead of time and affection. Sensible eating is a better solution than surgery.

The example set by parents is crucial – if they walk, children will walk; if they eat fruit and veg, children are more likely to eat fruit and veg. Dr Stoppard's advice is to avoid using food as a reward – offer fruit, nuts and carrot sticks as snacks instead of crisps and sweets, and be honest and face up to the problem.

One way of doing that is to keep a diary of everything your children eat and the exercise they take. The results could be surprising.

What is the Government doing about it?

Since last September, parents are being told if their child is overweight when they are weighed and measured at school. Previously, parents had to ask for the results. But the word "obese" has been banned for fear of stigmatising the child. Instead, those on the heaviest side will be described as "very overweight", a form of words dismissed by Tam Fry as "prissy".

Do we need stronger measures to help children who are too fat?

Yes...

* Fat children tend to develop into fat adults – obesity must be nipped in the bud.

* Obesity raises the risk of serious medical problems, such as diabetes and heart disease, later in life.

* Efforts to change eating habits and encourage exercise have failed – and childhood obesity is still increasing.

No...

* Removing children from their families to control their eating will do more harm than good.

* Targeting overweight children with tough measures risks stigmatising them and making things worse.

* Children must be taught good habits to last a lifetime, not punished for failing to meet the norm.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments