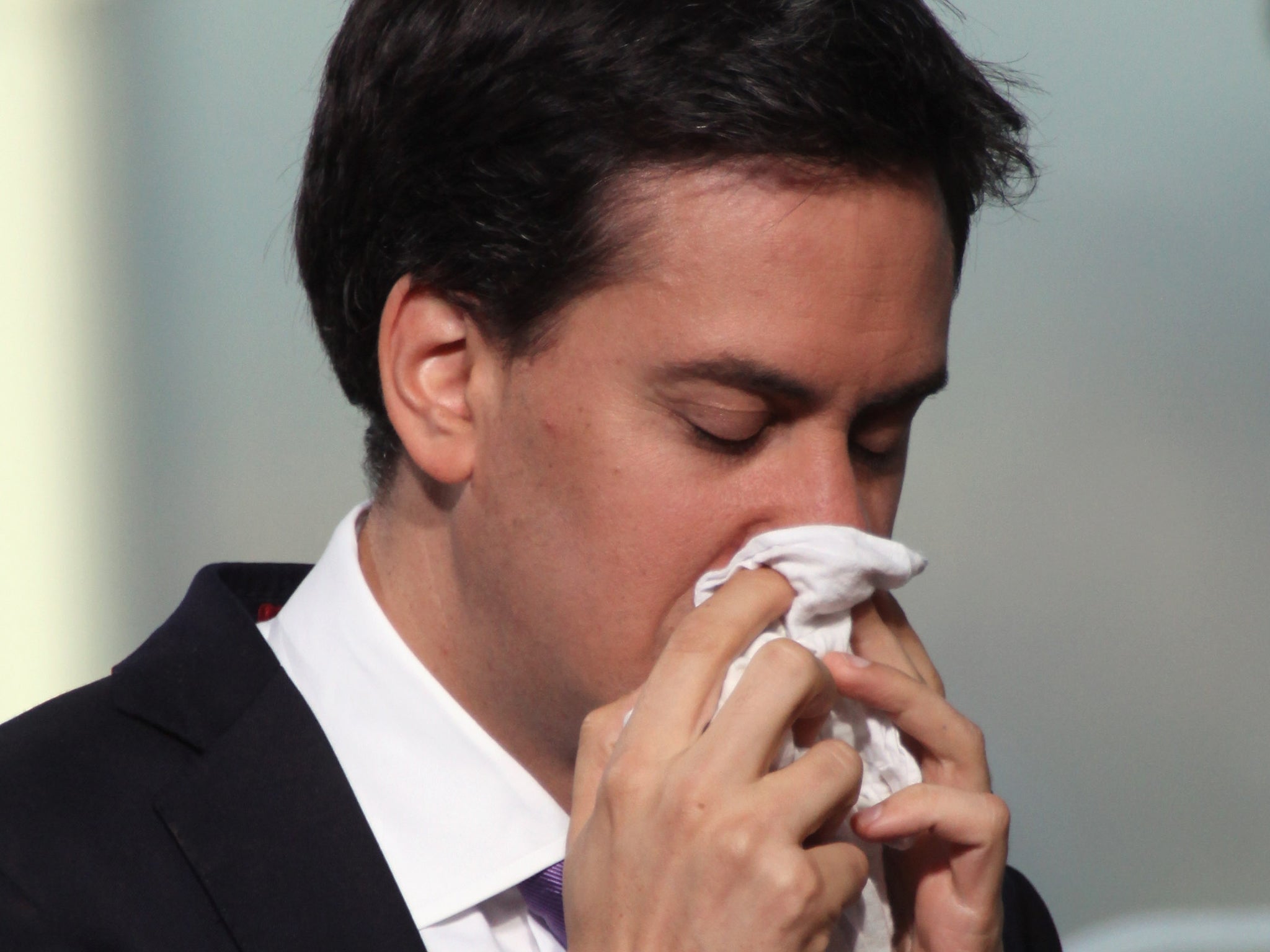

People who think they are less healthy 'are more likely to catch a cold'

Study indicates low self-rated health is associated with poorer immune system competence

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.New research finds that a simple self-rating of health accurately predicts susceptibility to the common cold in healthy adults ages 18-55.

Published in Psychosomatic Medicine, the study indicates that low self-rated health is associated with poorer immune system competence.

“Poor self-ratings of health have been found to predict poor health trajectories in older adults, including an increased risk for mortality,” says study leader Sheldon Cohen, a professor of psychology at Carnegie Mellon University.

“Strikingly, these associations remain significant even after accounting for the effects of objective indicators of health such as physical exams, medical records, and hospitalizations.”

Explanations for these robust associations have primarily focused on the premise that people judge themselves as healthier if they engage in beneficial health practices such as getting regular exercise, and being a nonsmoker, and if they have strong social ties and feelings of emotional well-being. In turn, people with these characteristics are less likely to get sick and more likely to live longer.

“We wanted to examine whether self-rated health predicted effective immune response in younger adults selected for their good health and whether this association was dependent on health practices and socioemotional factors,” Cohen says.

For the study, 360 healthy adults with an average age of 33 years assessed their health as excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. They were subsequently exposed to a virus that causes the common cold and monitored for five days for the development of illness. About one-third of the participants developed colds.

None of the participants reported poor health at the beginning of the study and few (only two percent) reported fair health—which was expected because the study targeted healthy individuals.

The investigators found that those who rated their health as very good, good, or fair were more than two times as likely to develop a cold as those who rated their health as excellent. Yet, socioemotional factors and health practices could not account for why those with better self-rated health were resistant to developing a cold.

Cohen believes the connection between self-evaluations of health and susceptibility to infection is tied to pre-morbid indicators—such as sensations, feelings, diffuse symptoms—of dysfunction of the immune system that tell us something is wrong.

“There are some things that we know about our bodies that aren’t easily detectable by our physicians,” Cohen says. “Our data suggest that this evaluation reflects how the immune system reacts to infectious agents.”

In an accompanying editorial in Psychosomatic Medicine, UCLA School of Medicine’s Hyong Jin Cho and Michael Irwin call the study a “unique contribution to the understanding of biological mechanisms of the link between self-rated health and morbidity.”

Cho and Irwin also suggest that the results raise the question of “whether self-rated health serves as a simple cost-effective screening tool for susceptibility to infectious or inflammatory disorders.”

Carnegie Mellon’s Denise Janicki-Deverts and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine’s William J. Doyle are coauthors of the study.

The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, and National Institutes of Health funded this research.

This article originally appeared on Futurity

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments