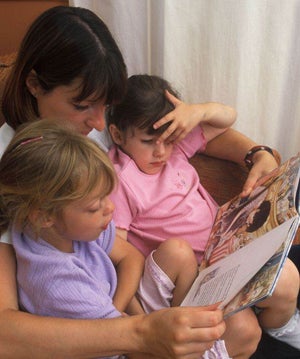

Parents who stumble over words may help children learn language

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Parents who stumble over their words need not worry – it may even help their children learn to talk.

Sentences peppered with "ums" and "ers" can be easier for children to follow than those uttered with complete fluency, researchers have found. The situations create natural pauses which allow the child to absorb what has been said and signal that there is a new or difficult word coming requiring special attention, they say.

The study by cognitive scientists at the University of Rochester's baby lab suggests that toddlers use their parents' stumbles to help them learn language more efficiently.

They cite the example of a parent walking with a toddler through a zoo who points to a rhinoceros whilst searching for the word. "Look at the, er, um, rhinoceros," the parent says. The fumbling helps alert the child that he is about to be taught something new so should pay attention, say the researchers.

As children are hearing many words that are new to them they need time to work out what they mean, so hesitations can provide them with the time to absorb what they are being told. With fluent speech they are apt to miss what comes next because they are still trying to work out what has already been said.

Richard Aslin, professor of brain and cognitive sciences at the University of Rochester and one of the authors of the study in Developmental Science, said: "The more predictions [a toddler] can make about what is being communicated, the more efficiently he or she can understand it."

The Rochester researchers studied three groups of children, aged from 18 to 30 months, who were sat on their parents' knee while they watched a pair of images on a screen. One of the images was of a familiar object (a ball or book) and one of an unfamiliar one with a made-up name (such as a "dax" or "gorp"). A recorded voice talked about the objects and when it stumbled the children were much more likely to look at the made-up image than the familiar one – almost 70 per cent of the time.

"We're not advocating that parents add disfluencies [stumbles and hesitations] to their speech, but I think it's nice for them to know that using these verbal pauses is OK – the 'uhs' and 'ums' are informative," said Celeste Kidd, the study's lead author.

The findings showed that the effect was only significant in children older than two years.

The younger children had not yet learned the fact that disfluencies tend to precede novel or unknown words.

Previous research has shown that it's not the quality but the quantity of speech that a child is exposed to that is most important for learning. Adults can also use "ums" and "ers" to their advantage in understanding language.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments