The city where residents have been taking mentally ill people into their homes for hundreds of years

Geel has a unique model of psychiatric care dating back to the 14th Century

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Half of Geel is crazy, and the rest is half crazy,” runs a joke often told about the Belgian city of Geel.

On the surface, it may seem unremarkable with its pretty market square and river views, surrounded by the Antwerp countryside.

But wandering around its plazas and cafes, visitors may notice that some of the residents seem slightly “eccentric”, and with good reason.

The city is home to hundreds of mental health patients, who live not in psychiatric hospitals but with local families as part of a unique model of care dating back centuries.

Mike Jay, an author and cultural historian, has visited Geel to explore its unusual system.

Speaking to The Independent, he said the perception of “madness” as we know it does not exist.

“The people of Geel very studiously avoid all that language in a way I think is quite admirable,” Mr Jay added.

“They tend to call them ‘guests’ or ‘boarders’, who are ‘different’ or ‘special’.”

After being assessed and signing a contract with the local health authority, the boarders move in with local families, who receive a stipend, and become part of their everyday lives.

As well as psychiatric conditions like psychosis and schizophrenia, people with severe learning difficulties are welcomed, and those with no diagnosis at all.

They are free to come and go as they please from the homes and any unusual behaviour is accepted, rather than being treated as a symptom to cure.

Mr Jay said the boarders are “quite a presence” in Geel.

“The streets are lined with cafes and you see these kind of people sitting around who look slightly different, but after a while you don’t really notice,” he added.

“They are very much part of the scene, they don’t really seem to be a different population, which is one of the amazing things.”

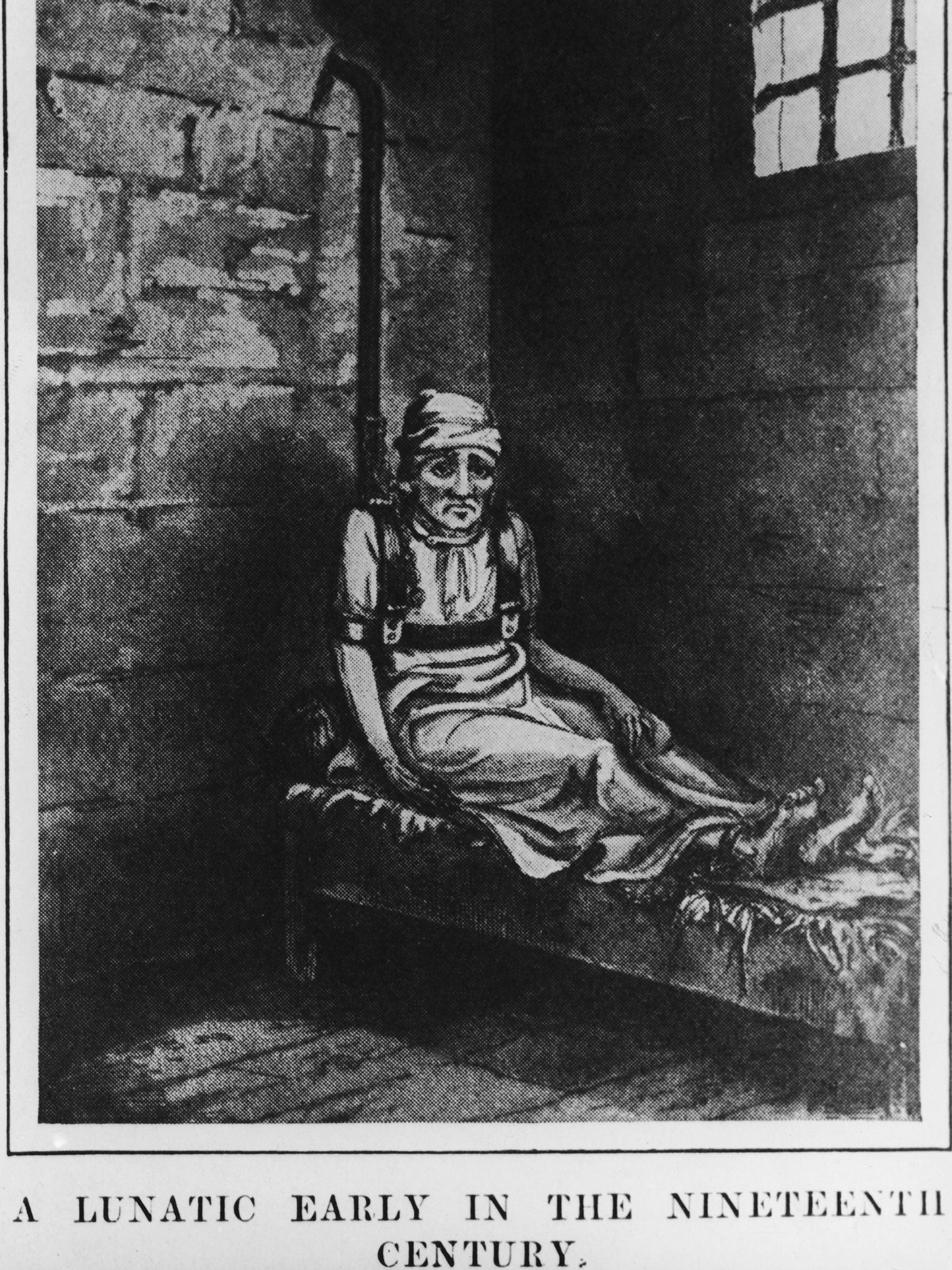

Geel has been famous for its model of psychiatric care for centuries, and with the system having back to the 14th Century, residents have a more open and accepting view of mental illness than can be found in most places.

Mr Jay said that the locals do not blink at the everyday sight of someone talking to themselves, and are unconcerned by “eccentric” behaviour that could spark a call to police in the UK.

“So much of what makes people think that people like that are different is people’s response to them – a bit scared, a bit awkward, they don’t really know how to handle them,” he continued.

“But when people open up, a lot of the problems we perceive just melt away.

“A lot of society sees these people as dangerous but they’re far more likely to be the victim of violence than to be violent themselves.”

Mr Jay believes that although perceptions are changing for the better in the UK, mental health still tends to be seen through a “criminal lens” and in terms of risk.

There are no such qualms in Geel, where boarders’ relationships with children they live with are considered vitally important.

“It’s a learning relationship for both sides, it’s seen as really good to have children grow up with boarders,” he explained.

“When I was there and they were saying that a lot of American psychiatrists were really struggling with the idea. They say: ‘What? You let these people near your children?’”

Few hosts in Geel would regard the practice as therapy but the city has drawn the praise of psychiatrists through the centuries for the success of its care, allowing people to live with their conditions in a loving environment without being separated from society or treated as a patient.

Such is the renown of the city that people journey from all over the world to join its system, and have done since the Renaissance.

The origins of Geel’s story can be traced back to the martyrdom of Saint Dymphna, a legendary Irish princess whose pagan father was said to have gone mad with grief and demanded his daughter’s hand in marriage.

To escape his passion, Dymphna fled to Flanders, but her father finally tracked her down and beheaded her in Geel when she would not submit to his wishes.

She became revered as a saint with powers to cure the mentally afflicted, and a shrine in Geel grew into a memorial, then a church in 1349.

A dormitory was added for a growing influx of pilgrims in 1480 but was soon beyond capacity, and the townspeople started housing visitors in their homes, farms and stables. The numbers kept on rising and the practice stayed.

Geel’s profile rose during the Renaissance, making it a destination for pilgrims as well as families who wanted to drop off troublesome relatives, and fears of cruelty in the asylums of the 20th Century drove more expansion, with a Polish prince among the city’s guests.

“There used to be three or four thousand boarders and now there’s only about three hundred,” Mr Jay said.

“It’s partly because of lifestyle changes – people used to be working farmers with their wives and children at home but now everyone is out at work and school.”

The historian thinks “creeping medicalisation” is also partly to blame for the decline, along with increasing legislation around care.

“It’s harder and harder for these kinds of initiatives and medical communities to survive in our mental health landscape,” he said.

“I think it’s a cultural thing in a way. We kind of expect mental health care not to be a problem for us, but for doctors and psychiatrists.”

Mr Jay said Britain’s mental health care system could learn a lot from Geel’s example, although he praised Jeremy Corbyn’s creation of a minister for mental health as a “good step forward”.

“What it tells you is that if we have a society where people have the time to manage this kind of community care, the need for psychiatric intervention is much less,” he added.

“I don’t think anyone can argue that putting people in a secure unit is the best place for them to recover.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments