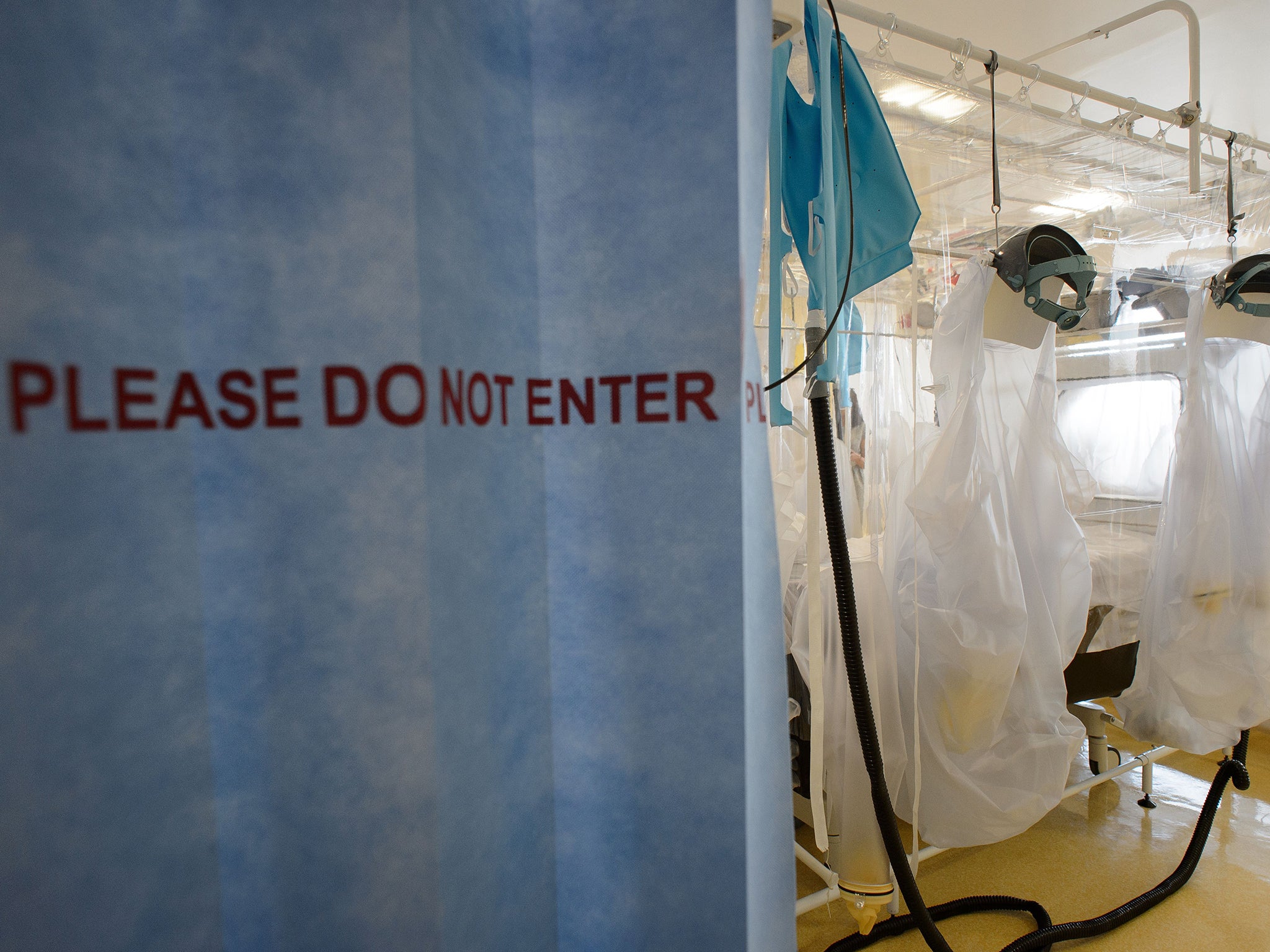

Discovery of 'Achilles heel' of viruses paves way for drugs to combat flu, yellow fever and Ebola

Scientists say new class of drugs could become antibiotics of viral infections

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A new class of drugs capable of targeting an array of different viral infections is on the horizon, after scientists discovered the Achilles heel of viruses ranging from influenza to Ebola.

New research into the way viruses invade human cells through their outer membrane has thrown up the possibility of blocking many kinds of viral infections before they become dangerous, scientists said.

Researchers have found a key human gene that plays a central role in determining whether a virus is able to penetrate a cell. The finding could be used to develop drugs that work against viral infections as diverse as yellow fever, dengue and flu, they said.

The scientists believe that the research could one day lead to a class of anti-virals that could do for viruses what antibiotics have done for many lethal bacterial infections that are now routinely cured with drugs.

“I think that’s what we would like it to be but in a different way. The way broad-spectrum antibiotics work is that they target a common bacterial pathway within the bacteria so they work across different bacteria,” said Paul Kellam of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute near Cambridge.

“This is turning this approach on its head by saying that since viruses have to get into cells to replicate then the commonality here is not the diversity of viruses, but the human cell that they replicate in - and by understanding what blocks this we get broad-spectrum activity,” Dr Kellam said.

Genome scientists have identified a human gene called IFITM3 that can explain why some people are severely affected by viruses such as influenza while others are only mildly affected or not affected at all.

“The question that is often asked is when there is a viral infection why do some people get severely ill whilst other have a moderate or mild disease or indeed not disease at all? Is it the pathogen or is it the human that has different response to the infection,” Dr Kellam tokd the British Science Festival in Bradford.

A study on the outbreak of swine flu in 2009 found that variants of the IFTM3 gene could explain why some people were hit hard by the virus, while others were hardly affected at all, he said.

“About 23 per cent of people when exposed to swine flu have no symptoms at all. But 0.1 per cent of people, which is about half a million people worldwide or a thousand or so in the UK, have severe symptoms or die, and it’s those individual we are interested in because it tells us how we fail to respond to a virus,” Dr Kellam said.

“When you have this variant you have a four to five-fold increased chance of severe influenza when exposed to a virus that is otherwise causing mild or no disease in the wider population,” he said.

Viruses are carried into cells by small bubbles or “endosomes” that pinch off and detach from the outer membrane as the move into the cells, carrying the invading virus with it.

The IFITM3 gene produces a protein in the surface of the endosome membrane that regulates how it behaves - whether it opens to release the virus or keeps it trapped inside, Dr Kellam said.

“These proteins decorate the outside of endosomes and even though the mechanism is not completely understood they seem to make the membrane less flexible so the virus cannot punch through and therefore gets trapped in the endosome and is shunted off to the garbage disposal in the cell,” he said.

“This now opens the possibility that in the future, as we understand the body’s own set of defences, there is a real arsenal of broad-spectrum anti-viral genes there, with a mechanism we can use to provide very good therapeutic targets for causing the same effect,” he added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments