Brain scan promises to identify the hidden sufferers of autism

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Autism could in future be diagnosed in 15 minutes from a brain scan – saving patients and their families years of suffering from a condition that can go unrecognised for decades.

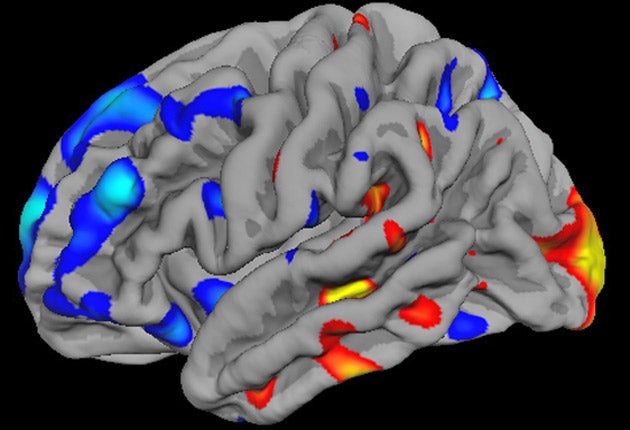

Scientists using facial recognition software have devised a method which can distinguish the autistic brain from the normal brain with 90 per cent accuracy. The method could lead to the introduction of screening for the disorder in children.

An estimated 600,000 people in Britain are affected by autistic spectrum disorders, which affect their capacity to interact with others. Sufferers have difficulty reading social situations and responding appropriately and may lead lonely and isolated lives as a result.

The condition ranges from the mild to the severe, but half of those affected are undiagnosed. Autism is a lifelong condition that is incurable but early diagnosis allows therapy to begin which can help sufferers to learn to cope with the condition.

Scientists at the Institute of Psychiatry in London, funded by the Medical Research Council, compared MRI scans of 20 adult men, previously diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorders, with scans of 20 normal brains.

By programming the computer to "learn" the pattern of the brains of autistic individuals, using the same techniques as in facial recognition and handwriting recognition, the scientists were able to distinguish the autistic brains from the normal brains. In addition, they were able to tell how severely the individuals were affected.

Christine Ecker, who led the study published in the Journal of Neuroscience, said: "We are very excited. We have been working on this for three years. We are saying this is 'proof of concept'. But it works very well in our clinic and we hope to roll it out with the help of the NHS in a year or two. The NHS would not have to purchase any new equipment – all it requires is a software update [for the MRI scanners]. It is very cost-effective."

The research had been carried out on adults and only in men because they outnumber women with autism by four to one, but will now be extended to include women and children.

Dr Ecker, a lecturer in the department of forensic and neurodevelopmental sciences, said the current method of diagnosing autism was expensive and stressful for the patient and their family and only available in the few centres with the necessary expertise.

"It takes the whole day and involves asking embarrassing questions such as how many friends they have and how they are doing at school," she said. "We do observations with the individuals and interview the parents. You can only do it with a team of three to four clinicians, it costs £2,000 and is not available in many parts of the country. We sometimes see people aged 50 or 60 who still have no diagnosis."

The differences between the autistic brain and the normal brain are too subtle to be seen with the naked eye but with the aid of the software, scientists were able to identify five parameters where differences could be detected.

"The scanner is a non-invasive means of testing for autism. It doesn't hurt and you can even go to sleep. The [computer programme] says yes this is autism or no it is not, and also gives an indication of the severity. It is a biologically plausible method and it has a lot of implications. There is a strong need for a quicker, cost-effective biological test. We still can't cure autism but we can do a lot to help people affected cope. It is really important to identify those with the disorder as early as possible so they can get treatment," Dr Ecker said.

The programme proved less reliable at distinguishing cases of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). The researchers plan to develop a new software program specifically to diagnose ADHD.

Declan Murphy, professor of psychiatry at the Institute, who supervised the research, said it raised challenging questions.

"Simply being diagnosed means patients can take the next steps to get help and improve their quality of life. Clearly the ethical implications of scanning people who may not suspect they have autism needs to be handled carefully and sensitively as this technique becomes part of clinical practice."

Experts welcomed the advance but warned further studies would be needed. Professor Paul Matthews, of the Centre for Clinical Neurosciences, Imperial College London, said: "The findings suggest that sophisticated approaches for the interpretation of brain scans could help to diagnose particular forms of autistic spectrum disorder, although they do not yet offer an approach to more confident, early diagnosis. This work now needs to be extended to study affected children, for whom the impact of more certain prognostic information could be much greater."

The National Autistic Society said: "While further testing is still required, any tools which could help identify autism at an earlier stage have the potential to improve a person's quality of life by allowing the right support to be put in place as soon as possible. However, diagnosis is only the first step. It is part of a wider struggle to enable people with autism to access appropriate support at every stage of their life."

Case study: 'I went 20 years without a diagnosis'

Joe Powell, 34

Joe spent 11 years in silence. Between the ages of 15 and 26, he spoke only to his parents and his sister – with others he communicated by means of written notes.

His mutism was, he says, a symptom of his Asperger's syndrome, a mild form of autism only diagnosed when he was 20. Had it been detected earlier, he might have avoided his decade of isolation from the speaking world.

A scan of his brain conducted by the Institute of Psychiatry last week (though he was not part of the recent trial) confirmed his diagnosis on the autistic spectrum.

"If I had been diagnosed when I was a child my life would have been a lot better. I would not have had to go through all I went through. I would have had the support I needed from an early age," he said.

At school, he misbehaved, got into trouble and fell behind his peers. Then he changed schools and found, as the new shy boy, that people responded positively to him for the first time. He became obsessed with being nice and being quiet.

"It was like bulimia – I felt really guilty when I spoke and people had to reassure me it was all right. I had to be the quietest person in the world – I was scared to go into any environment where people might not be sensitive to my condition."

He lived in a care home in Manchester run by the National Autistic Society and then when his family moved to south Wales, followed them to a care home in Newport.

In the last decade he has made a remarkable recovery and is now a campaigner and national speaker on autism, living independently in his own flat and studying for a degree in English and creative writing at the University of Wales.

"There was nothing for people like me. I went for 20 years without a diagnosis," he said.

In numbers...

600,000 The estimated number of people in the UK with autistic spectrum disorders, including Asperger's Syndrome, a milder version of autism

4 Number of men with the condition for every woman

30,000 Number of people affected by classic autism, the severest kind (about five in every 10,000 cases). This figure has remained unchanged for 50 years

12-fold The increase in autistic spectrum disorders among children in the past 30 years, according to some estimates. The reasons are thought to be improved diagnosis and awareness, and the inclusion of milder conditions in the diagnosis.

1943 The year autism was first identified – it has attracted increased interest in the past decade. The condition became controversial because of a claimed link with MMR vaccine which has since been discredited.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments