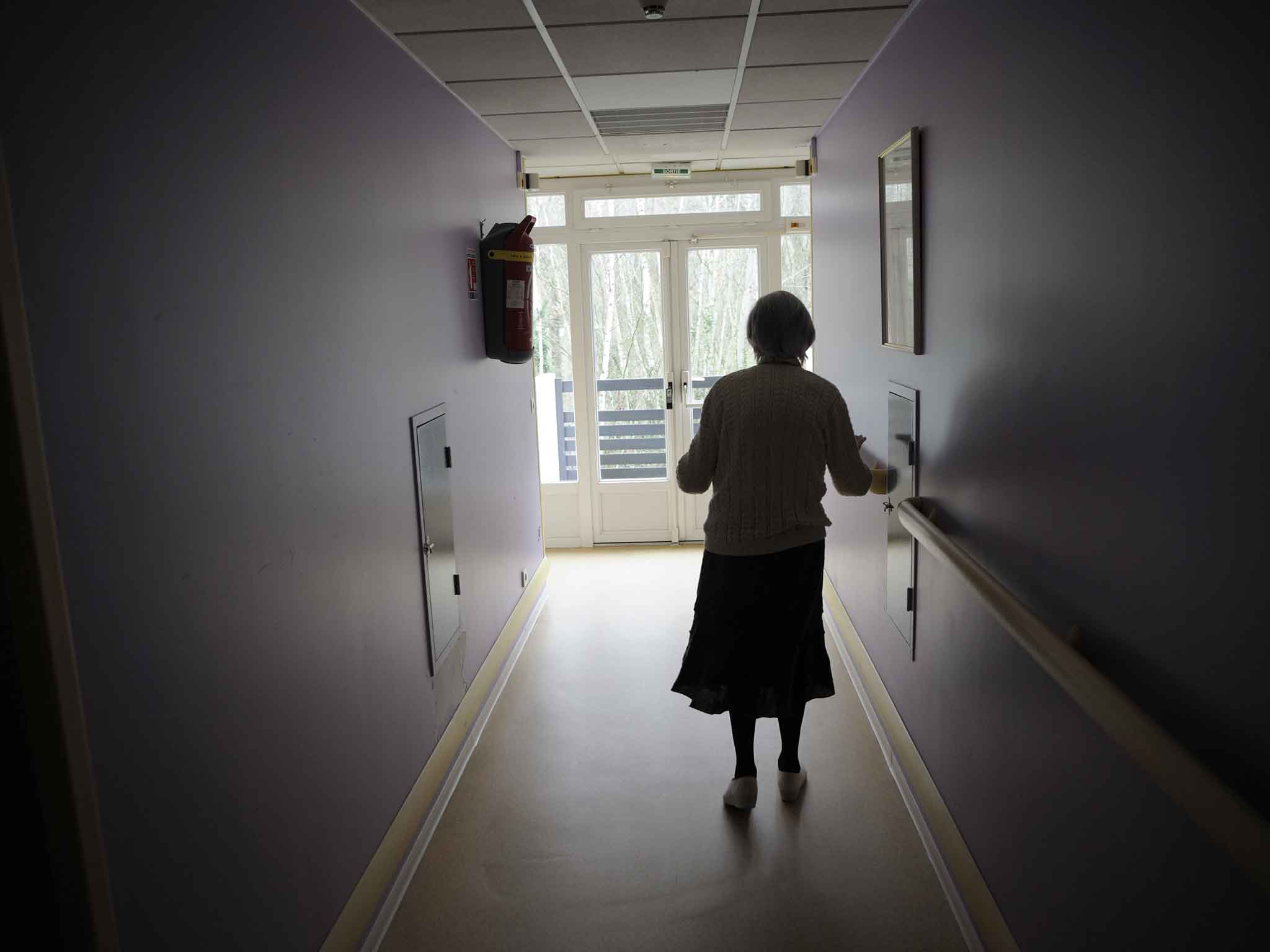

Alzheimer's disease may be a transmissible infection, study suggests

Disturbing possibility raises questions about certain surgical procedures

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The “seeds” of Alzheimer’s disease may be transmitted from one person to another during certain medical procedures - possibly including blood transfusions and dental treatment - following a study into people who died of a separate brain disease after receiving injections of growth hormone, a study suggests.

An investigation has shown for the first time in humans that Alzheimer’s disease may be a transmissible infection which raises questions about the safety of some surgical procedures that could inadvertently pass the brain disorder from one person to another.

Scientists emphasised that the new evidence is still preliminary and should not stop anyone from having surgery. They have also stressed that it is not possible to transmit Alzheimer’s by living with or caring for someone with the disease.

However, the findings of a study into eight people who were given growth hormone injections when they were children have raised the disturbing possibility that Alzheimer’s can be transmitted under certain circumstances when infected tissues or surgical instruments are passed between individuals.

Until now, it was thought that Alzheimer’s occurred only as a result of inheriting certain genetic mutations, causing the familial version of the disease, or from random “sporadic” events within the brain of elderly people, said Professor John Collinge, head of neurodegenerative diseases at University College London (UCL).

“What we need to consider is that in addition to there being sporadic Alzheimer's disease and inherited or familial Alzheimer's disease, there could also be acquired forms of Alzheimer's disease,” Professor Collinge said.

“You could have three different ways you have these protein seeds generated in your brain. Either they happen spontaneously, an unlucky event as you age, or you have got a faulty gene, or you've been exposed to a medical accident. That's what we're hypothesising,” he said.

“It’s important to emphasise that this relates to a very special situation where people have been injected essentially with extracts of human tissue. In no way are we suggesting in any way that Alzheimer’s is a contagious disease. You cannot catch Alzheimer’s disease by living with or caring for someone with the disease,” he added.

The eight adults, aged between 36 and 51, all died of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) after receiving contaminated hormone injections as children. Autopsies on their brains revealed that seven of them harboured the misfolded proteins associated with the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease - unheard of in this age group.

They did not, however, find the “tau” protein tangles associated with the later stages of the disease, which means the seven individuals did not have full-blown Alzheimer’s, although they may well have developed it had they not died of CJD, Professor Collinge said.

The study, published in the journal Nature, eliminated other possible reasons for the presence of these so-called amyloid-beta (A-beta) proteins and came to the conclusion that they were most likely transmitted as protein “seeds” in the growth-hormone injections - Alzheimer’s patients are known to have the A-beta proteins in their brain at least10 years prior to the onset of clinical symptoms

Questions remain about whether these protein seeds could also be transmitted on surgical instruments used in other operations. It is know that the prion proteins behind CJD and Alzheimer’s stick to metal surfaces and can survive extreme sterilisation procedures such as steam cleaning and formaldehyde.

There is also the question of whether Alzheimer’s disease could be passed in blood transfusions, given that animal experiments have shown this to be possible, with at least one documented instance of CJD being transmitted in a blood donation taken from someone who was incubating the disease but not showing any symptoms.

“It is not clear here with what we are seeing that this is relevant to blood transfusions, and epidemiological studies have been done in the past looking for links between Alzheimer’s disease and blood transfusions and they have not shown an association - that’s not to say it could never happen,” Professor Collinge said.

“Certainly with vCJD, which is the form of CJD associated with mad-cow disease, there is infectivity found in the blood and there has been four documented cases in the UK of vCJD from a blood donor who went on to get vCJD, so it can occur,” he said.

“Certainly there are potential risks in dentistry where it is impacting on nervous tissue, such as root-canal treatments and special precautions are taken for that reason. If you are speculating whether a-beta seeds are transmitted at all by surgical instruments one would have to consider whether certain types of dental procedures might be relevant,” Professor Collinge said.

“Although it is not cause for alarm that it is in any way contagious, it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t think about whether there might be accidental routes by which these diseases might be transmitted by certain medical procedures,” he added.

In a statement issued afterward, Dr Collinge said: “Our findings relate to the specific circumstance of cadaver-derived human growth hormone injections, a treatment that was discontinued many years ago. It is possible our findings might be relevant to some other medical or surgical procedures, but evaluating what risk, if any, there might be requires much further research. Our current data have no bearing on dental surgery and certainly do not argue that dentistry poses a risk of Alzheimer’s disease.”

Between 1958 and 1985 some 1,848 people in Britain, mostly children, received growth hormone injections made from tens of thousands of homogenised pituitary glands derived from the brains of human cadavers.

The NHS switched to synthetic growth hormone in 1985 when scientists realised that pituitary-derived hormone could be a route for transmitting CJD. Up to 2000, there were 38 known cases of “iatrogenic” CJD resulting from growth hormone injections in the UK, but this figure is likely to rise further because of the exceptionally long incubation period of the disease.

Of the seven who had the early signs of Alzheimer’s, four had severe deposits of amyloid-beta protein, three had moderate deposits and one had traces.

Importantly, they also had protein deposits in the blood vessels to the brain which is also seen in animals that have been infected with human Alzheimer’s disease via injection of brain material into their abdomens - a similar transmission route in the eight individuals injected with growth hormone.

Dame Sally Davies, the Government’s chief medical officer, has played down the significance of the research saying that it was a small study on only eight samples.

“There is no evidence that Alzheimer's disease can be transmitted in humans, nor is there any evidence that Alzheimer's disease can be transmitted through any medical procedure,” Dame Sally said.

"I can reassure people that the NHS has extremely stringent procedures in place to minimise infection risk from surgical equipment, and patients are very well protected,” she added.

John Hardy, Professor of Neuroscience at UCL, said: “I think we can be relatively sure that it is possible to transmit amyloid pathology by the injection of human tissues which contain the amyloid of Alzheimer’s disease. Does it have implications for blood transfusions? Probably not, but this definitely deserves systematic epidemiological investigation. Does it suggest Alzheimer’s disease is infectious through contact? Almost certainly not.”

Doug Brown, director of research at Alzheimer’s Society, said: “While these findings are interesting and warrant further investigation, there are too many unknowns in this small, observational study of eight brains to draw any conclusions about whether Alzheimer’s disease can be transmitted this way.

“Injections of growth hormone taken from human brains were stopped in the 1980s. There remains absolutely no evidence that Alzheimer’s disease is contagious or can be transmitted from person to person via any current medical procedures.”

What is a prion?

Alzheimer’s disease is now considered a “prion disease”. Prions, short of proteinaceous infectious particles, are misfolded proteins that carry the ability to trigger further proteins to misfold, leading to debilitating brain disorders, such as CJD and kuru in humans, BSE in cattle and scrapie in sheep.

Prions are unique in being an infectious agent without any genes, unlike viruses or bacteria. They are extremely tenacious, sticking to metal surfaces of surgical instruments and surviving the high temperatures and chemical agents that kill off infectious viruses and microbes.

Stanely Prusiner of the University of California coined the word Prion in the early 1980s and his pioneering work on them led to a Nobel prize in 1997.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments