Why should children's toys be segregated along gender lines?

Clare Dwyer Hogg speaks to the parents who are fighting back against the stereotypes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As advertisements go, it was pretty great. Set to a rewrite of the Beastie Boys' song "Girls" , three young girls use their stereotypical pink toys – dolls' prams, teapots, ribbons and the like – to construct a Rube Goldberg machine.

It's called the "Princess Machine", and this is tongue-in-cheek, because, at the end, it changes the television channel from a princess programme to the GoldieBlox channel. Goldie: a young engineer who makes things happen.

The idea of the GoldieBlox toy is two-fold: there is a narrative as well as a construction toy, so girls will read stories, and help Goldie solve problems by building things. The ad went viral, was hailed as authentic girl power, and is now one of four finalists with a chance of being chosen to air at next year's US Super Bowl.

This coup is despite a legal wrangle with the Beastie Boys, who, at the end of last month, got lawyers on the case: the ad was pulled, and two open letters later, reappeared online, with an anodyne lyric-free musical accompaniment instead of the rabble-rousing original. It looks like the legal fires may have been put out. But the conversation GoldieBlox was participating in - and further stoked - is still raging. This week, there was hot debate when research by the University of Pennsylvania suggested that men's and women's brains are wired differently.

That theory seems to fit with Debbie Sterling's thinking. She's the founder of GoldieBlox, and an engineer from Stanford University. In April, she gave a TED talk to explain why she ditched her job to make toys. Women are a minority in engineering: she wanted to change that.

Her theory is that skills such as spatial awareness aren't innate, they're learned. And one of the ways they're developed is by playing with construction toys, which boys do but girls often don't. It seems pertinent that the company ran foul of copyrighting laws just as they were trying to wrest the psychological copyright of construction and engineering play from the "boys" aisle. But critics question why the company is pitching itself for girls in the first place.

Are there even such things as girls' toys and boys' toys? The manufacturers and retailers would lead us to believe so, but there is a groundswell of antipathy towards this trend, and it feels as if change is in the air.

In November last year, the campaign group, Let Toys Be Toys, was formed with the aim of persuading shops in the UK and Ireland to stop using signage that divides along the gender divide. So far, it's succeeded in getting 13 retailers to agree, including big hitters such as Toys R Us, Sainsbury's, Tesco, and Debenhams.

Tessa Trabue, one of 10 parents who make up active membership of the campaign, is particularly proud that Boots removed the "boys" signage from above the science toys as a result of their pressure. The mechanisms of the campaign are simple but effective. "[It's] a mixture of us and our supporters taking images and tweeting pictures from shops," she explains. As soon as those images are out there, the group follows up with letters and phone calls.

"For the majority of stores this has worked," she says. "Often when we point it out to them, there's a genuine look of realisation, and they say they haven't meant to alienate children from playing with certain toys." Trabue appreciates that sometimes it's hard for shops to make a decision on how to organise toys, given that the packaging shouts one gender or the other. That's a subject the group is going to tackle in the new year. But given that the group has nearly 5,500 followers on Twitter, the purchasing power they represent already seems to be an inspiration for shops to think more creatively about layout.

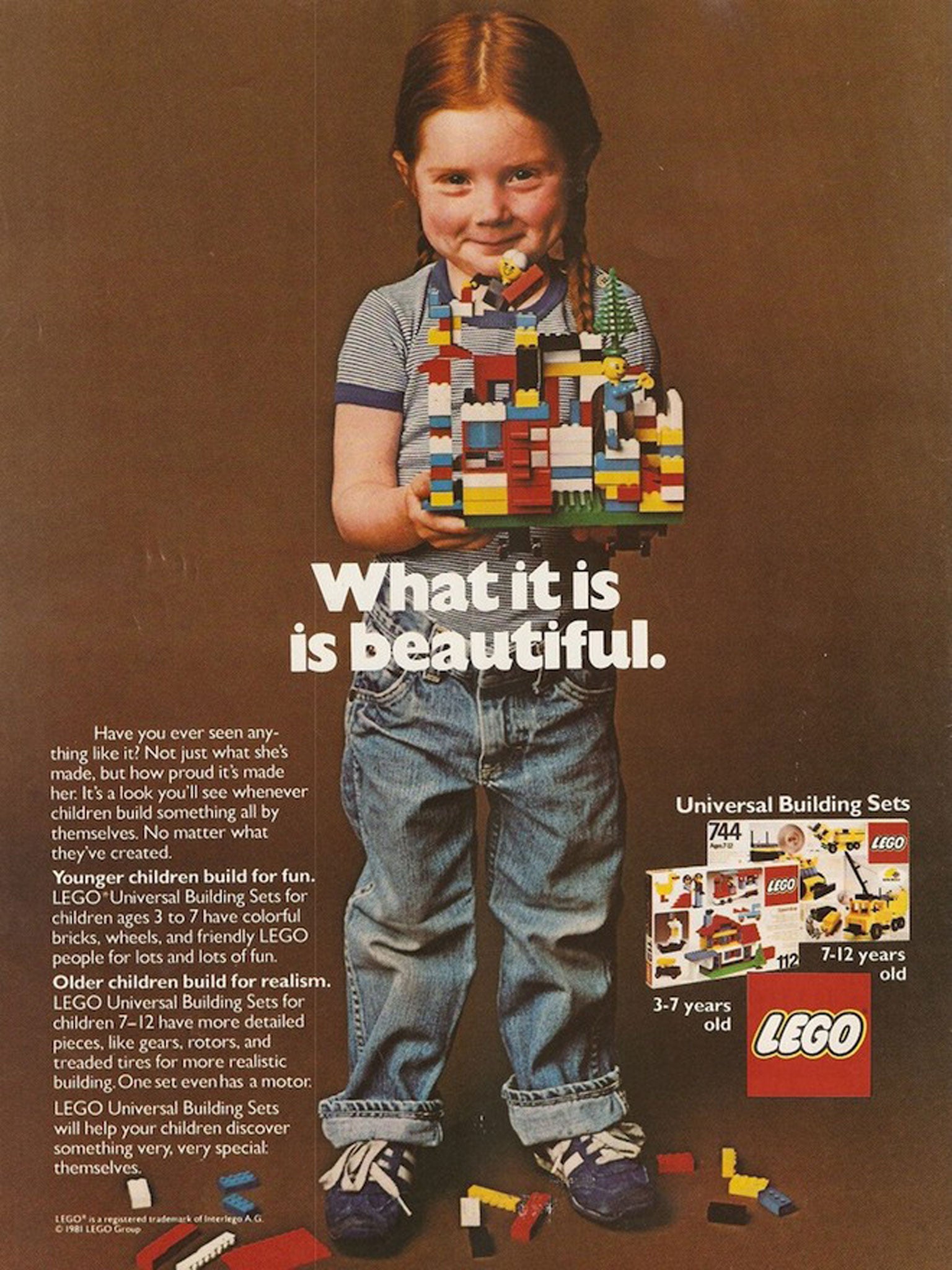

Although it's not an exact science, Trabue says that the shift towards dividing toys happened in the 1990s, when a proliferation of pinks and blues, nurture vs. construction, flooded the market. "If you look back to the 1970s, it wasn't like this," she says, referencing an advertisement for Lego from that era, where the little girl in denim dungarees (no pink) holds up what she's made (no, not a beauty salon, just a building). The logo reads: "What it is is beautiful."

Some elaborate contortions have occurred in the intervening years to get us to the "Lego friends" range we have today. The picture on the box is of a perky group of Disney-esque cartoon girls, arms around each other like the archetypal girl band.

Their appearance can't be further from what a Lego character looks like (although the Lego friends inside the box, whether they're in karate costume, a magician or horse-riding, are particularly groomed, with a bit of the Cheryl Cole about them, which is more than slightly disturbing).

Earlier this week, historian Dr Thomas Dixon, of Queen Mary, University of London, posted a picture of the latest toys from Lego on Twitter: "I love Lego, but not this. Violence for boys; pets and trees for girls…" I got in touch with him about what he feels the ramifications are for children, and he emailed back, assuring that he is not an expert, just a parent and Lego-lover who is frustrated. "For me," he writes, "the sadness is the limitation being placed on children's development and imaginations by this kind of thing. Many parents can see through it and try to ignore it. But each individual advert is part of an all-pervading fog of cliché and prejudice, which is very hard to escape."

That's the real challenge as a parent: how to mitigate and manage the choices. Of course, some children will naturally be drawn to certain modes of play – I know first-hand that despite never encouraging my four-year-old daughter to like pink, she loves to play as a "Rose (her addition, still not sure what it means) Fairy Princess". She also loves to dress up as a mermaid, pirate, ballerina, shepherd (yes – foam crook and all), and Batman. Last week she chose to buy a magazine that was overwhelmingly pink. It might even have been called Pink. This week she chose Bob the Builder magazine, and spent a great deal of play time walking around the house "fixing" doors with the free plastic spanner that came with it, and calling through her "builder phone" for back up.

"Sally the Builder is on her way" she told me, professionally, before hanging up and turning to fix an imaginary puncture on her scooter. Perhaps the point is that the options should be open to enjoy the frilly side of life and the practical, both of which are on the creative spectrum. But we need to become cognisant of an insidious trend that is dictating what our children spend their time doing in their formative years. It doesn't make sense.

Our children are fortunate enough to be born in a time that ostensibly offers them an enormous amount of freedom and choice, yet a parent who buys their son a doll would generally be considered to have an agenda that was counter-cultural. Given that we laud men who choose to divide the childcare with their child's mother, it would seem to fit that boys are allowed to develop their nurturing skills, in the way that their female peers are always prepared to be mothers.

Similarly, if we tell our girls they can do anything they want when they grow up, but only teach them skill sets in certain areas, they'll never have the keys to open the doors they want. Or we tell them they are beautiful no matter how they look, yet the dolls they play with are disproportionately thin, with pert features and breasts, and feet shaped to wear high heels. The arguments against Barbie, Bratz dolls et al have been well rehearsed, but surely the battlefield for parents is how their children are already pigeon-holed before they can speak. Once you start to notice, it becomes very clear how prolific this pernicious practice is: I had a little gulp this week when I saw that even good old Kinder Egg has pink and blue versions.

The reality, though, is that finding a place as an alternative, independent toy maker in this field is difficult. Lucie Follett, the co-creator of the Lottie doll which launched in August last year, remortgaged her house to do it, and told The Independent that trying to introduce a toy that is unusual is a "massive struggle because retailers aren't interested in taking a chance with a new, non-TV advertised product".

Scientifically in direct proportion with the dimensions of a nine-year-old, Lottie can stand on her own two feet. Literally. And metaphorically: she comes in different versions that include her dressed as a pirate queen, in a karate costume, or as robot girl. Her accessories are, respectively, a treasure chest, karate instructions, and a build-it-yourself robot sidekick. What she won't have is make-up, or jewellery.

Lottie was the result of Follett reading an article by Dr Margaret Ashwell, OBE: "It was about dolls and their impact on girl's perception of body image," Follett says. "This raised many issues, and we decided to conduct focus groups and began working with experts until we finally arrived with Lottie."

Follett is keen to stress that the company has had to take "baby steps" to gain traction with the retailers – which might be why the adventurous Lottie has a website that features a large amount of pink. The actual doll, though, which has already won 17 awards here and in the US, is a much cooler customer. "We really want to try to celebrate all the different ways to be a girl," Follett says.

Her ethos echoes that of the Pinkstinks group, set up in 2008 to challenge gender-segregation and sexism towards girls that it saw in toys, marketing and media messages. Its slogan is "There's more than one way to be a girl" and its convinced Sainsbury's to change the labelling on costumes (doctor outfit: for boys; nurse and beautician: for girls). Its aim: to promote positive images for little females.

Some parents feel that the choices offered for how to be a girl are so limited that they need to work very hard to guard against the tsunami of pink. Hana Loftus, the director of an architecture practice in Colchester, has two daughters aged four and five. "Shocked by the amount of pink", she and her partner "boycott it" in their shopping, making sure not to buy anything with girly branding. "We buy and make lots of other stuff," she says. " They love jigsaw puzzles, and they're into making and drawing."

Of course, she says, her daughters do a lot of playing with baby dolls, but it's just one of the options, along with making robots, reading, or drawing. She doesn't go so far as to forbid them to play with unsuitable presents they are given, but, she says, "it's amazing the level people assume your daughter wants to be a princess. It's terrible gender modelling." What Loftus has started to think more carefully about recently is what her girls see her doing. "For instance, a mother may want her kid to grow up interested in engineering, but how knowledgeable is she about how stuff works?" she says. "Does she throw up her hands in horror when the dishwasher doesn't work or does she fix it? I am more aware now that I should do things like fix my bike when they're awake."

She followed the launch of GoldieBlox, and while she can see the virtue in their mission, she isn't completely convinced. "I'm not a massive fan," she says carefully, explaining she does think trying to encourage girls into construction is admirable. "Just – why do you need to make engineering 'girly'?"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments