The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

The truth about the chemicals you breathe, eat and drink

Is our exposure to chemicals really a ticking time-bomb?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.All too often the use of the word “chemicals” in the news, in advertising and in common usage has the implication that they are bad. You never hear about chemicals that fight infections, help crops grow or lubricate engines. That is because the chemicals doing that job are called antibiotics, fertilisers and engine oil, respectively.

As a result of the emotive language often used in conjunction with “chemicals”, a series of myths have emerged. Myths that Sense about Science and the Royal Society of Chemistry are debunking with the publication of Making Sense of Chemical Stories. Here are five of the worst offenders.

1. You can lead a chemical-free life

Despite the many products that claim otherwise, using the term “chemical-free” is plain nonsense. Everything, including the air we breathe, the food we eat and the drinks we consume, is made of chemicals. It doesn’t matter if you live off the land, following entirely organic farming practises or are a city-dweller consuming just processed food, either way your surroundings and diet consists of nothing but chemicals.

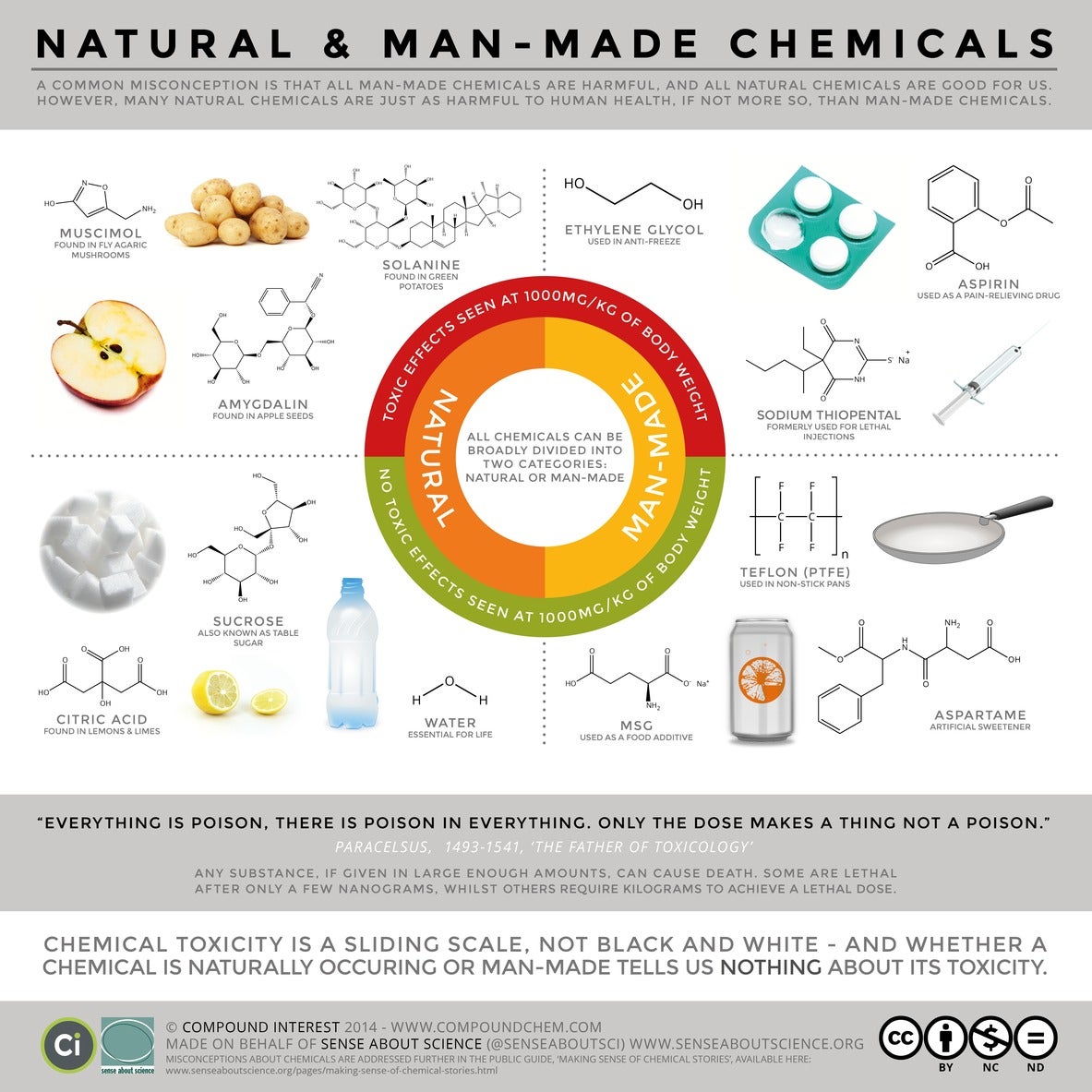

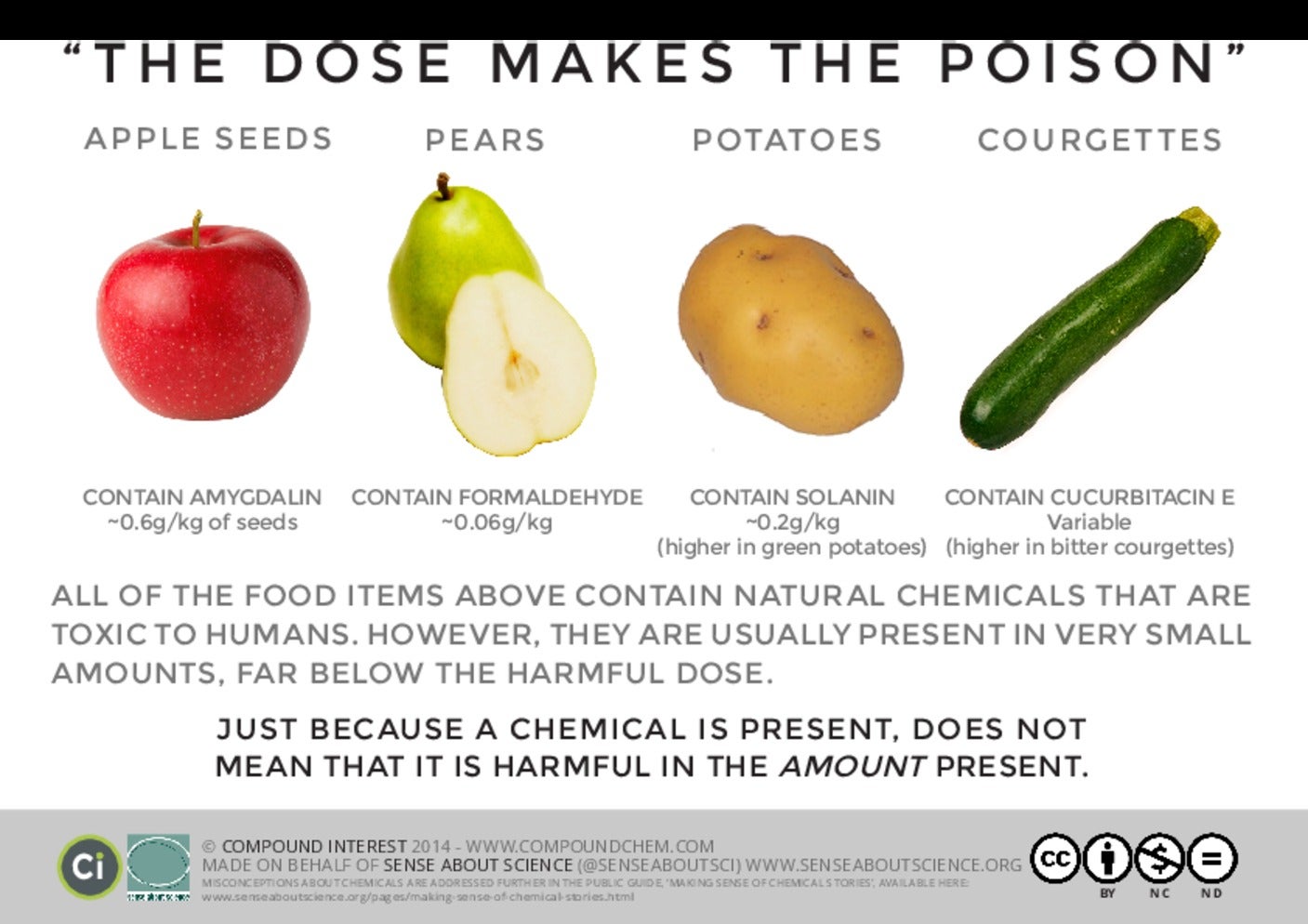

2. Man-made chemicals are dangerous

So we have established that there is no way to lead a chemical-free existence. But surely natural chemicals are better than synthetic ones?

Nope. Whether a chemical is man-made or natural tells you precisely nothing about how dangerous it is. Sodium thiopental, for example, is used in lethal injections but it’s about as toxic as amygdalin, which turns up in almonds and apple seeds. What makes one of these chemicals dangerous and the other part of your healthy five-a-day is quite simply the quantity that you consume.

Granted there are many documented cases of man-made chemicals that have been banned due to health concerns. But on balance chemicals have done far more good than harm. A good example is brominated flame retardants which are no longer used in furniture due to allegations of unpleasant side-effects. However these worries should be balanced against the estimated 1,150 lives saved because the chemical stopped furniture fires spreading.

Even substances that are upheld as terrible cases of chemical pollutants, such the pesticide DDT, have their place. The World Health Organisation support its use for control of malaria transmitting mosquitoes stating:

DDT is still needed and used for disease vector control simply because there is no alternative of both equivalent efficacy and operational feasibility, especially for high-transmission areas.

3. Synthetic chemicals cause cancer

News outlets are fond of reporting about research showing “links” between particular chemicals and occurrences of cancer and other diseases. Sometimes the stories even claim that a substance definitely causes cancer or definitely cures it.

But more often than not these reports only cover part of the scientists’ conclusions. They just mention that an effect on cancer (either positively or negatively) was seen in the presence of a chemical. This is what we call a correlation, but it does not necessarily imply a causal link.

For example, the number of diagnosed autism cases correlates with sales of organic produce, but no one would seriously suggest that man-made chemicals used on farms somehow protects people from autism.

The point is that correlation on its own isn’t that useful, unless it is accompanied by other observations such as a plausible mechanism to explain it. But once a correlation is seen then scientists can start looking for that other supporting information.

4. Chemical exposure is a ticking time-bomb

Phrases such as “cocktail of chemicals” and “time-bomb” are pretty emotive, and they certainly make for good headlines. But we permanently live among a cocktail of chemicals and have done so ever since life first evolved in a chemical soup.

So why have we suddenly become more aware of all the chemicals in our environment? In part, it is due to amazingly sensitive technologies that allow minute quantities of chemicals to be detected. It really isn’t difficult for a chemist to find minute quantities of antibiotics in a swimming pool or cocaine in water supply.

5. We are subjects in an unregulated, uncontrolled experiment

There is no conspiracy. The reality is that the use, manufacture and disposal of chemicals are strictly regulated and controlled.

Each new synthetic chemical used as a food ingredient passes through a series of safety tests before it is allowed by the relevant body, such as the UK Food Standards Agency. New medicines go through clinical trials, which are even more rigorous tests, before the drug agency, such as the US Food and Drug Administration, allows it to be marketed. Even the tiny amount of waste chemicals produced by university research labs are managed according to the hazardous waste management rules of local governments.

Chemists in academia and industry have to adhere to these regulations in the process of inventing or manufacturing amazing new chemicals to better our lives.

Mark Lorch is a Senior Lecturer in Biological Chemistry at University of Hull

nullThis article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments