The Holocaust's youngest survivors: Three people born in a concentration camp on their incredible bond

Three babies were born within weeks of each other in Mauthausen Concentration Camp. Now 70, they tell Giulia Rhodes about survival against the odds

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

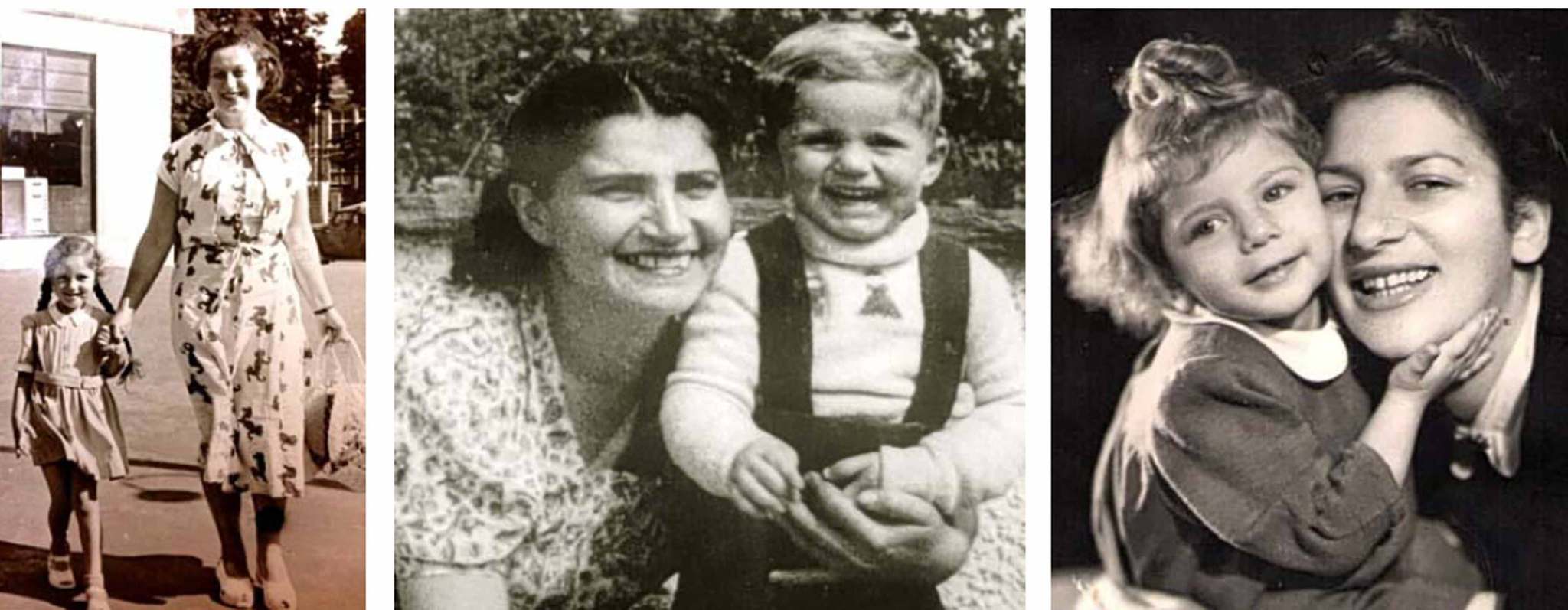

Your support makes all the difference.On 5 May 1945, the soldiers of the US Army's 11th Armoured Division arrived at Mauthausen Concentration Camp in Austria. Among the tens of thousands of starving, sick prisoners they discovered, there were three tiny babies, born in unimaginable circumstances, in the final weeks of the war: the Holocaust's youngest survivors.

The new mothers were oblivious to each other's existence, yet last weekend their three children – having just celebrated their own 70th birthdays – walked together through the gates of Mauthausen at the commemoration of the camp's liberation.

"They are family. I have siblings now," says Eva Clarke, who was born on a wooden cart in the shadow of the prison camp's gates on 29 April 1945, just hours after her mother's arrival there.

The final gassing at the camp took place the previous night. The gas chamber was then disabled as SS guards began to flee in the face of advancing allied troops.

Mark Olsky was born eight days earlier, in the open coal wagon being used to transport all three women to Mauthausen. Hana Berger Moran was born on 12 April, her mother giving birth on a wooden plank on the factory floor at Freiberg (in German Saxony).

The women had all been sent to work in the aircraft factory camp from Auschwitz the previous year. Their selection was overseen by Josef Mengele. Forced to line up naked in front of the Auschwitz doctor, the so-called Angel of Death, each had denied the pregnancy which, if detected, would almost certainly have led to their deaths.

"I asked my mother how she survived, how she hid her pregnancy," says Hana, who now lives in California, where she works in the pharmaceutical industry. "She had lost three babies before me. She said, 'well, I wanted to have you, so I did everything I could to stay alive. You saved me and I saved you'."

Moving down the line from Hana's mother, Priska, Mengele had asked the same question of another woman. Priska saw him squeeze milk from her breast. She was directed to the opposite corner of the parade ground.

Hana began to learn her story as a young child in Czechoslovakia. At the end of the war the American medics who had saved the desperately sick and dehydrated baby had pleaded with Priska to travel to the US. She refused, telling them she must return to her native Bratislava to wait for her husband.

Like those of the other two babies, Hana's father never returned. He is thought to have died on a death march from Gliwice slave-labour camp in January 1945. "When I was six, I asked my mother what a Jew was," Hana says. "Someone had called me it at school. She showed me a photo of my father and my grandparents. She said they were Jewish and because of that they were killed."

Priska never remarried. "She said there would be nobody like my father." She focused all her "incredible instinct to keep going" on her career as a teacher and on her daughter. "She never emphasised her suffering. She would simply say, 'we are here, we move on'," Hana says. "We had to fill the shoes of all those who had died."

Hana had a recurring childhood fantasy that her father had survived. "Every time I saw a tall man with a moustache I would stare longingly," she says. Hana first visited Mauthausen in 1960, with Priska. "When I go there, I shut down," she says. "However hard, my mother always said we must bear witness."

Priska died, aged 90, in 2006. "She was a tremendous driving force in my life and she will be for ever. Every time I see my scars [from the infected boils that nearly killed her as a baby], I remember."

Priska had often told Hana she believed there were other babies born to her fellow prisoners, but she never knew their fate. Five years ago, at the 65th anniversary of Mauthausen's liberation, she was able to meet two of those now known to have survived.

Eva, a speaker with the Holocaust Educational Trust who lives in Cambridge, had written, like Hana, to the veterans association of the 11th Armoured Division. The two made contact with each other and then with Mark, whose son Charlie had been researching his family history. "All my life, my mother and I had thought we were the only ones, and then I discovered these other two," Eva says.

The two women met each other, as well as a number of the soldiers who had freed them, in Austria. "We sat in a café all afternoon. We were each telling bits of our story, laughing or crying. We walked into the camp holding hands behind the veterans. It was simply incredible."

Like Hana, Eva learnt her story bit by bit as she grew up. Returning to Prague after the war, Eva's mother, Anka, had learnt that her husband, parents and sisters had all died. "My mother felt very grateful to be given proof that my father was killed – a friend had witnessed his shooting – because so many came back and spent the rest of their lives trying to find out."

In 1948, she married an old acquaintance, Karel Bergman, who had worked in the UK for Fighter Command. He too had lost his family in the war and soon after the wedding, Karel, Anka and Eva moved to Cardiff.

"I was always asking my mother about her life – her schooldays, hobbies. She would tell ordinary family stories with snippets of her wartime experiences," Eva says. "The first thing I remember was asking my mother why she had the initials A N on a bag. They were her initials from her marriage to my father. She told me I had two daddies. One was killed in the war and now I had another one."

Anka was always an optimist, Eva says. "For no logical reason, she assumed she would survive. Knowing she was pregnant helped. She said she had a reason to survive, but that ultimately it was just down to luck.

"She told me she would never have predicted being able to withstand such an experience. She tried not to think about what was going to happen next week, tomorrow, this afternoon. In Auschwitz, it was minute by minute."

It was when Eva had her first son, Tim, 40 years ago, that she had a real sense of the terror her mother must have felt, giving birth alone, herself starving, to a baby who might be taken from her. "How on earth did she do that, in those circumstances, with nothing?" she asks. "When I was pregnant, my mother would fuss over me, reminding me to take my calcium, my vitamins. Then she would laugh, 'ah, you don't need any of them – look at you'."

Before Anka died in July 2013, she was visited by Hana and Mark, a semi-retired hospital doctor from Wisconsin. It was as if hey were her own children, she told them.

Mark's mother, Rachel, died in February 2003. "She always assumed no other babies could have survived," Mark says. Rachel was one of the last to be transported to Auschwitz, from the ghetto in Lodz, Poland, in November 1944, with her three sisters. "They gave her bits of food they could scarcely afford to lose and it was these she believed which allowed me to grow and her to produce milk."

When Rachel left Mauthausen, she was "a 26-year-old old lady". Her hair turned grey and within two years she had lost all her teeth and several inches in height. She, too, was a widow. She had, Mark says, expected to die. "Keeping it going as long as possible became important."

In 1946, she married another survivor, Sol Olsky, who had lost his wife and five-year-old son. The family lived first in Germany, then in Israel, before moving to America in 1958 (to avoid Mark being conscripted into the Isreali army).

Mark has one picture of his father, obtained from an old girlfriend, that Rachel had found in Israel. Her own pictures had all been destroyed in the war.

Although Rachel spoke more readily about her experiences to her grandchildren than to Mark – "I didn't ask, as I knew it made her and my stepfather so sad" – he was aware of the effect of her experiences throughout her life. "She would go into a panic if she thought I was in an unsafe situation. I didn't get to do some things other children, young people might do. It took her a long time to see a policeman with a gun and not expect it to be pointed at her. She always feared it would all happen again."

Mark told his mother that he planned to attend the Mauthausen commemoration. "She talked about it every now and then," he says. "As she arrived, she looked in one direction and saw a beautiful valley.

"Then she saw this horrible, evil place. She said you would have to shoot her before she would agree to go back."

For Mark, the reunion with his fellow camp babies in the place his mother had so narrowly escaped death, was "overwhelming".

"I tried to imagine what it was like for her, but how can anyone say they could? I walked through there healthy, well fed and safe."

'Born Survivors' by Wendy Holden (Sphere, £20) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments