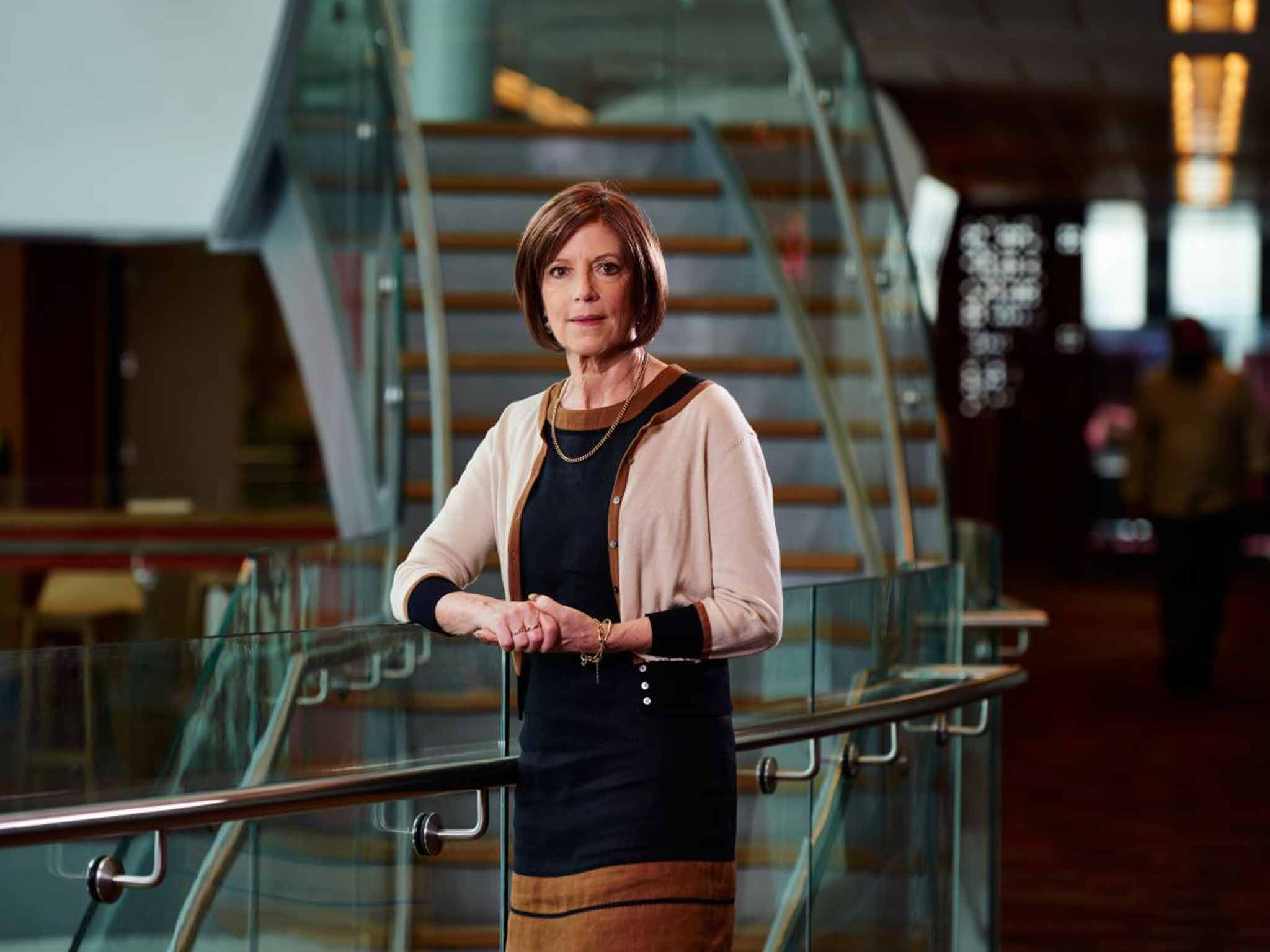

Sue Lloyd-Roberts: Why waiting for a stem-cell donor to treat my cancer is my scariest challenge yet

As an award-winning TV reporter, Sue Lloyd-Roberts is used to facing danger.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I get so cross when I receive cards and messages saying "I am sure some good will come out of this" or "Look for the silver lining". What possible good news can you find in the fact that you have been diagnosed with an acute blood cancer with, in many cases, a dismal prognosis?

But I have come up with two. I have a great wig, which means every day is "a good hair day". Gone are the days when I would spend hours washing and blow-drying my hair. The wig does the trick. Some of my friends are cruel enough to say it is much better than the original.

And, for the first time in memory, I have beautifully manicured nails. Now that I am no longer working for the BBC nor tending to the small hotel that I run with my husband in Spain, they have grown long. They look like the hands of a beautician serving behind a counter in Harvey Nichols or Selfridges. So, I have found a small silver lining, but it doesn't really compensate.

Everyone who gets diagnosed with cancer must say, "Why me?" and I admit that I feel more justification than many in asking the question. I have always been something of a health and fitness fanatic. I neurotically watch my weight, weighing myself every day and enjoying a health-laden Mediterranean diet. My passion is hiking in the mountains in the Serra de Tramuntana, where I live in Mallorca. Just a few days before I was diagnosed, I was climbing mountains and going on six-hour treks.

I had a dizzy spell while loading the dishwasher in Spain, followed by seven or eight hours of severe nausea. I felt better the next day and thought nothing of it. I am a doctor's daughter and was always taught never to bother a doctor except in extremis.

But my husband, Nick, got on to an online doctor service, and, £30 later, he was told to advise me to see someone. Four days later, I queued up at A&E ("Urgencias") in Palma. The doctor was irritated, suggesting that if it had taken me so long to get there, there couldn't be that much wrong with me. Grumpily, they did all the tests. He came back an hour later, looking most apologetic. My white blood cells were dangerously low and I was admitted to hospital for more tests. A later biopsy diagnosed acute myelodysplastic syndrome, a form of leukaemia.

I found that, although I speak fluent Spanish, my brain froze. I simply could not work out what he was saying or understand the implications. I needed to go home to be among people who spoke my own language. White blood cells affect your immune system and so I had to wear a mask on the flight back to London. I went to University College Hospital (UCH) in London, where they confirmed the diagnosis, and, soon after, I was admitted for my first course of chemotherapy.

I have had friends and family who have had chemotherapy and it has always involved going to outpatients, having a drip stuck in the arm and then going home to recover. The problem with my condition is that it knocks out your immune system and you are at constant risk of infection, so you have to stay in hospital for weeks at a time. My first course took three weeks and, because I caught flu midway through it, my second course took six weeks.

I found the incarceration hard to bear. I have always been an active person. I took solace in reading and when I was too weak to hold a book, I listened to Radio 4 and CDs. The evenings would be long and lonely and so I saved box sets to watch at night, which made watching Breaking Bad by myself quite scary. My dear friend Yasmin Alibhai-Brown gave me the remake of The Forsyte Saga, which was rather more cheering.

Being on the 15th floor of UCH made it even harder. I got unrivalled views across London, with Regent's Park looking tantalisingly close. I don't know whether I could have coped without the frequent visits from my husband, who has got into the habit of reading aloud Maigret novels to me and my children, George and Sarah. And certainly I would not have survived without the constantly caring and cheerful nurses.

All was going well. I had two weeks off after my second course of chemotherapy in order to breathe the air of the outside world and recharge my batteries and I was due to be readmitted for a stem-cell transplant on 27 May. The hunt had been on for donors for several weeks. The stem-cell register in the UK is hosted by the Anthony Nolan Trust. It has access to one million donors in the UK and millions more worldwide. I think the one they found for me was from Germany.

Donors often sign up when they are young and idealistic, in their late teens or early 20s. The trouble is that they are often not contacted for 20 years thereafter, when their tissue type comes up as a match for someone like me. If they can be found, they will be asked to have an injection over four days to stimulate the stem cells and then a simple blood transfusion, which is all that is needed to "harvest" the stem cells.

But they may have moved to another address since they first registered, they may be on holiday or working abroad when they are needed, or they may no longer be up to it. This third possibility is what happened to mine. He had turned up to be tested, was found to be a good, 9/10 match, but failed his medical test, which takes place a few days before the stem cells are due to be "harvested". Maybe he was found to be HIV-positive, maybe he had an infection. I shall never know. Not even my doctors know, because the whole donor business is conducted in the utmost secrecy. But for me, it was a bitter blow.

The transplant process is a scary one. I had been advised to try to put on at least three kilos, to fortify my body against what was about to be thrown at it, and to prepare myself for a hard endurance test. The actual transplant involves only a half-hour transfusion, but the days that follow are the most risky – the host can reject the graft. I was warned that I could end up in intensive care and my life could be at risk. But I was ready for it because a stem-cell transplant is all that can help me. Anthony Nolan is now looking for a new donor for me.

It goes without saying that the more donors who are registered, the more chance there will be for those in need of a transplant to find a match. "We at Anthony Nolan would encourage anyone between the ages of 16 and 30 to join the Anthony Nolan register," says Ann O'Leary, the trust's head of register development. "It's such a simple, easy thing to do and you could potentially save someone's life."

Meanwhile, the crazy thing is that I feel so well. People who come to visit me expect to see this wan, thin shadow of my former self. Instead, I am nicely plumped out by the instructions to put on weight, I am told I look well, and I have this fab wig.

I have to pinch myself to remind myself that I am in fact very seriously ill. I wake up to these lovely, sunny mornings and enjoy four seconds of drowsiness before the reminder of what is wrong hits me like a cruel blow. It is always in the back of the mind, making it hard to concentrate and leading to what people call "chemo brain". My memory is shot to pieces and I have to search for words. I doubt there is any medical explanation. It must be just that this horrible thing is always there, clouding the brain. I am now waiting for the new donor and, for the first time in 40 years, praying a lot.

To register as a donor, or donate money to the Anthony Nolan Trust, go to anthonynolan.org or justgiving.com/BBCPatientAppeal

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments