Maytree charity: Sanctuary for the suicidal - one mother's story

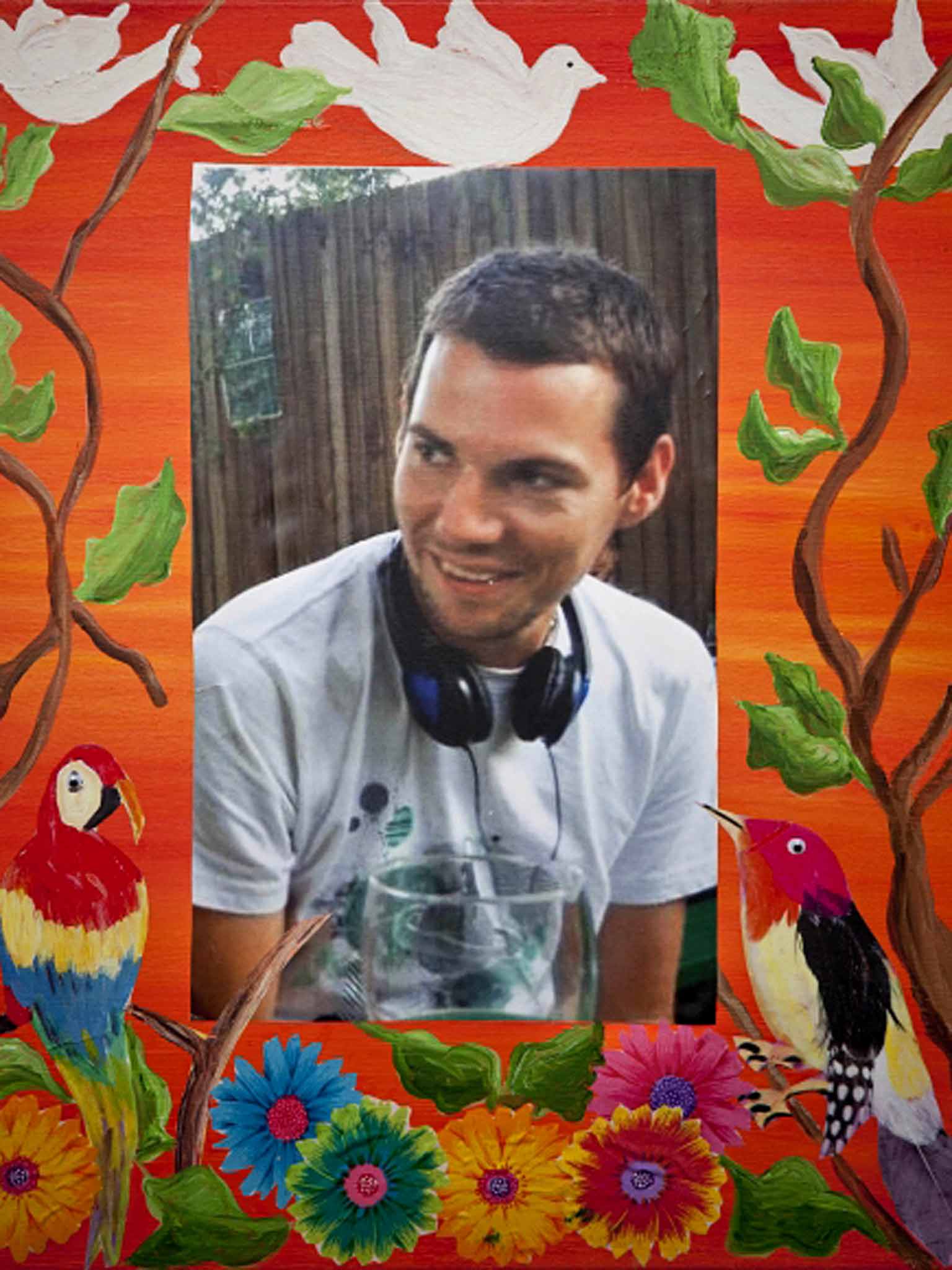

While her son was spiralling downwards into the deep depression that eventually killed him at the age of 30, Carol O'Brien searched desperately for a place that could help him to live with his illness – and finally found the Maytree charity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Three and a half years ago, my youngest son, Rob, took his own life. He was 30 years old. He was found locked in his flat by his two brothers with the help of the police. Although this was something I had long feared, it came as a terrible shock. Part of me died that day.

Rob first tried to end his life by taking an overdose of paracetamol when he was about 15. He was in hospital for quite a while afterwards and was transferred to a specialist unit because of the potential damage to his liver. He was referred to a child psychiatrist, who told us that Rob was very depressed.

Talking with Rob later, he told me he was just trying to feel a sort of near-death experience. I knew there were things going on at school. There were stories about Rob being bullied and there was some trouble over a girl, but it didn't seem like anything more than usual teenage stuff. His dad and I had split up some years before and he had been living with his dad but had then moved in with me.

The trouble at school continued and eventually we took him out and sent him to a private college. It was really good for him and he did well at English and art and got a place at Leeds University. But he found it very difficult to settle. Eventually, he admitted to me that he was hating it. "It's the most alienating experience of my life," he told me. He seemed very distressed, so I went up and brought him home.

After this, he took a number of jobs in local bars or restaurants. A pattern began to emerge. He would get a fairly menial, low-key job and do really well at it. This would lead to a quick promotion and more responsibility than he could handle. He would then quit the job, basically running away.

Rob was a really popular person, described by his many friends as the life and soul of a party. Walking down the street with him was extraordinary – every other person seemed to know him and be really pleased to see him. He was very funny and gregarious. When he was feeling good, he would throw himself into things 110 per cent. He was generous and extravagant with his money. He also loved cooking. I have many lovely memories of the recipes he made for us with expensive and often hard-to-find ingredients.

Around this time, Rob and a friend decided to start their own business. With others, they bought a rundown pub in Islington and started renovating it. Around the same time, he got married to a lovely girl in a fabulous wedding in Yorkshire.

I don't think there was enough income from the pub to pay two managers. Rob was working long hours and becoming very stressed. Eventually, it just became too much. He and his friend had a terrible argument and Rob walked out.

A short while later, he completely disappeared. This was something he would do when things became too much for him, sometimes for days or even weeks. He was found in Brighton, trying to suffocate himself under the pier. He was returned to London and placed in a local psychiatric unit. It was a really scary place. There were people in there who were obviously really disturbed. Rob was depressed but he was certainly not violent. The staff seemed to be shut inside a little glass cubicle just inside the door of the ward. When he was discharged, he was supposed to receive counselling. It wasn't available, so his name was put on a waiting list. He had one home visit by members of a mental health team and they left a telephone number for us to ring in an emergency. We needed to use it once, and the call went straight to answerphone. No one ever called us back.

For a while, Rob felt better, but it wasn't long before the pattern started again. Things went wrong in his job and he walked out. He disappeared again. His wife and I drove round everywhere searching for him and ringing all his friends. The anxiety was awful. You want so badly to protect your child, but when he's an adult it's so difficult. Although Rob could be very outgoing and gregarious, he was also a very private person and as his illness took hold he would become very secretive. I am quite sure he was bipolar, although this was never diagnosed. He hated the idea of anyone knowing.

Around this time, I happened to read about a new charity called Maytree. It was described as a "sanctuary for the suicidal" – the only one of its kind in the UK. It just happened to be around the corner from my house in north London. I applied to be a volunteer and once a week I'd go in for a few hours and just talk with the guests. They were often very distressed and on the brink of suicide, or perhaps had made an attempt that had failed, leaving them still feeling suicidal. At Maytree, people are accepted exactly as they are. There is a culture of warmth and friendliness built around the kitchen table, with shared meals and games as well as really in-depth talks about what has brought them to contemplate suicide. One of the things I learned from working there is how terribly isolated people can be once they become depressed. They withdraw and become unable to engage. It doesn't work for everyone, but I saw the difference it made to a large number of people and I know it saved many lives.

About a week after Rob's latest disappearance, he called me. He was in central London and in a really bad way. He had been living rough and was unkempt and very distressed. I rang Maytree, who said to bring him in. We went straight there in a taxi.

Rob stayed for four nights, the maximum allowed. It was amazing for him. It really brought him through and he seemed back to his old self. Not long after, he got a job at a children's nursery, which he adored. The kids loved him. I have many photographs and good memories of his work there, including him organising the children to do huge paintings in the style of Pollock and Matisse and a trip to the park with Rob dressed as a bear hiding behind the trees.

I had managed to get him an appointment with a psychiatrist recommended by Maytree. He didn't give Rob a diagnosis as I'd hoped, but instead prescribed him with a hefty dose of medication. This seemed to stabilise him and he continued to take it for a few years. But in August 2010, the prescription ran out. I know Rob made an appointment with his GP, but I don't know if he actually went to it or not. I rang the surgery but they refused to tell me. I understand the importance of patient confidentiality, but that just seemed so uncaring. They knew his history and just weren't prepared to work with me at all.

Around Christmas 2010, it was obvious that things were bad. Rob eventually admitted he had stopped taking his medication. He said it was suppressing his moods and changing his personality. In spite of warnings on the packet to come off it slowly, under medical guidance, he just went cold turkey. It affected him badly. He sort of shut down. He was clearly trying to keep it together, but he wasn't sleeping and he was becoming very ill. I could hardly get near him emotionally or physically.

There were other things going on that we didn't know about. His girlfriend left him (he had already separated from his wife) and he'd just lost his flat. Just before Christmas, he had some difficulty at the nursery and once again he walked out of his job. It was the same pattern all over again, but in this case it was particularly tragic. He seemed to have got himself into a corner where he felt he didn't deserve anything good.

He finally killed himself on 11 March 2011. Of course, I look back and say could we have done more? Could we have done something else? But part of me knows, in a way, he's at peace now. It was terrible seeing him in that state. He was so very ill. He believed he would never get better.

But the lack of support continues to haunt me. Maytree filled a huge gap between nothing and psychiatric hospital admission, but without that there was literally nothing. I strongly believe his stay at Maytree gave him those last few years of happiness working at the nursery.

Throughout this whole period I was basically on suicide watch. I was given no help. I was treated at best as irrelevant and at worst the cause of his problems. I remember a senior member of the local mental health service once telling me that this was the best there is. It doesn't say much.

I haven't yet been able to go back to Maytree because it's just too painful, but I hope one day to return to volunteering there. I know you can't persuade someone that life is worth living when they genuinely believe it isn't. But for the vast majority of people, feeling suicidal is temporary. People can come through it, but only with the right help and support.

For more information visit maytree.org.uk

Interview by Lena Corner