Safety posters from the golden age of accident prevention: Have we lost the art of communication at a cost of countless lives?

Simon Usborne uncovers the poignant personal story that inspired the collection in a new book.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For Paul Rennie it was, as he puts it, his "Tutankhamun moment". A lifelong passion for posters had produced a growing personal collection, a shop in Folkestone and – eventually – a career as a graphic design academic at Central St Martins College of Art & Design. Soon, perhaps inspired by a family tragedy, he embarked on a research project that focused on accident-prevention posters, particularly those dating to the Second World War.

"My own grandfather was killed in an 'unspecified accident' in the Merchant Navy," Rennie, who is 56, says. The death at sea left his grandmother and her two children destitute. Rennie's father, who was only three at the time, was put into a Merchant Navy orphanage. "It's important to remember that each of Britain's major industries were so dangerous that they ran orphanages for the children of deceased workers," Rennie says. "I remember seeing the railway orphanage at Woking. They put it next to a railway, for God's sake, just to remind them."

But as he began his research, Rennie found large gaps in the archives. There was no tradition of preserving these posters. "Then I got a call out of the blue and the caller said, 'You'll never guess what, but we've discovered the archive in a warehouse that had remained locked for 20 years.'" The posters belonged to RoSPA, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents, which emerged in London in 1916 to tackle a rash of road accidents during wartime blackouts. Posters were a part of the charity's earliest campaigns and, in an increasingly dangerous world, RoSPA soon developed a broader mission to prevent accidents of all kinds.

"Very few people seem to understand what we have achieved in 98 years," says Tom Mullarkey, RoSPA's chief executive. "But once you talk about things such as seat-belt laws, moulded plugs and fire-retardant furniture, they begin to see it."

Rennie and RoSPA worked together to publish the lost posters, which date from the 1930s to the 1970s. In Safety First, Rennie explores the societal, historical and artistic significance of the sorts of striking and often beautiful posters that were once commonplace on factory floors, police-station noticeboards and billboards.

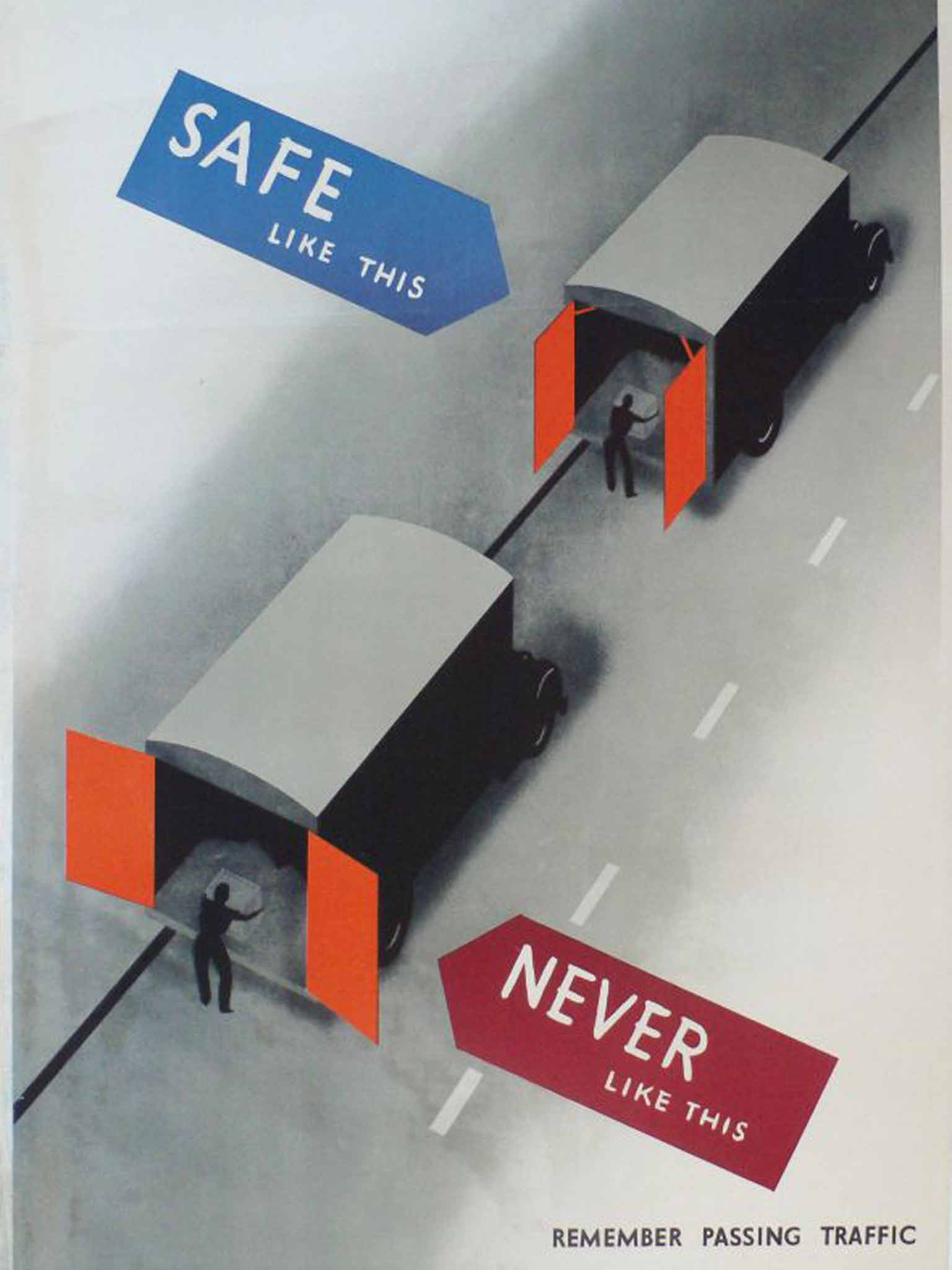

His own favourite is typical. It warns van drivers not to let their rear doors swing into traffic. The message could not be simpler yet the poster, which dates to 1946, is also a work of art, inspired by the works of El Lissitzky, a renowned Russian-born artist who blurred the lines between those disciplines with striking, Modernist works of bold, geometric shapes.

After the war, a generation of Soviet war propagandists turned their talents to safety in Britain, bringing a new sense of modernity to our streets. "It's health and safety rendered in Constructivist style, which is just fantastic," Rennie says. They joined British artists, including Cyril Kenneth Bird, aka the cartoonist Fougasse, most famous for his "Careless Talk Costs Lives" posters. Yet the posters of the era, and through to the 1970s, were more than visually pleasing. What is striking is how many of them convey messages that would trigger howls of "'elf'n'safety gone mad" today: "Bad weather! Extra care at crossings" and reminders to turn off your iron, bend the knees when lifting things, and flick on your car's headlights.

"Part of my interest has been to try to debunk that idea," Rennie says. "I'm always suspicious when people talk about common sense. Often people don't know stuff not because they're daft but because no one has explained it to them. Simple messages need to be repeated frequently, because the minute you scale back people start behaving stupidly again."

The posters are also deft and steer clear of shocking imagery. As well as speaking simply, "designers such as Bird treated people as intelligent," Rennie says. "The default is to shout at people but they stop listening when you do that. You have to be cleverer than that."

But since the state gave up responsibility for producing this kind of material, largely handing it over to the makers of television soaps, charities or advertising agencies, Rennie and RoSPA believe that the disappearance of simple yet smart messages have deprived us not only of art but – ultimately – lives, a regression not helped by the popular maligning of health and safety.

"Workplaces and roads are much safer now," Mullarkey says. "Yet deaths in the home and in leisure are going up. And while road-safety posters might still exist, Mullarkey says that elsewhere, "we were doing much more in the early part of the last century" than now, adding: "The result is that we have a population not tuned into this threat."

Rennie's father later excelled and became an architect, raising his own family in an artistic home in Guildford that inspired his son's career. "I imagine he was plagued with feelings of guilt and what-if questions about what would have happened without the accident," Rennie says. "He never spoke about these things to me." He adds: "I hadn't pieced all this together when I started my safety-poster work but, as Sigmund would say, it explains a lot."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments