NHS in crisis: Reasons to be cheerful – the problems are serious but not insuperable

The country’s most cherished public institution has improved consistently and is still better than healthcare in other nations

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was Enoch Powell, Minister of Health from 1960 to 1963, who observed that the NHS presented the “unique spectacle” of an institution that was run down by everyone involved with it.

Over half-a-century later, healthcare has been transformed yet attitudes remain unchanged. The NHS is our most cherished institution, but one we love to hate.

There has never been a time when the NHS was not in crisis. In the 1980s, funding pressures led to the Thatcher review and the Tory market reforms. In the 1990s, rising waiting lists prompted Tony Blair to declare record investment. Now, another funding crisis is opening a new debate about the future of the country’s most revered public service.

Yet today’s NHS is infinitely better than it was even a decade ago. Shorter waiting times, more staff, more operations, cleaner hospitals, better equipment, safer care, lower death rates. There has never been a better time in history to fall sick.

Memories, alas, are short. Back in 2000, when the Blair government launched the NHS Plan heralding a historic boost in funding, the service was struggling, with thousands of patients waiting up to two years for treatment. In 2002, Downing Street crowed that the “tanker had been turned” when a health department progress report showed the longest waits were down to 15 months. Fifteen months! It is scarcely believable that ministers could have celebrated such a figure today.

There were at the time 250,000 patients who had waited over six months for hospital admission. When ministers announced a target to eliminate these long waits they were roundly mocked. It was fantasy, critics complained.

Today if the NHS slips below its target of admitting nine out of ten patients within 18 weeks, the current maximum wait for non-urgent surgery, headlines scream that the NHS is in “crisis”. That is less than four months, and the average wait is around seven weeks. The long queues for treatment which were synonymous with the NHS for so many decades seem like ancient history now.

Among the patients waiting more than six month in 2002 were 4,000 in need of heart surgery who were at risk of dying before they reached the operating table. Some did. Today anyone with chest pain is seen in two weeks and those in need of surgery operated on in weeks, not months.

There has been a 60 per cent increase in the number of operations performed on the NHS, from 6.5 million in 2002-03 to 10.5 million in 2012-13. Hospital infections have been reduced to less than a quarter of their level in 2006. Who now remembers the gloomy, grimy A&E departments where your feet stuck to the floor?

Infant mortality is down, deaths from cancer and heart disease have been falling steadily and life expectancy has been increasing. In mental health, which has suffered the tightest squeeze since the Coalition Government took power, access to specialist help and crisis resolution teams is considered among the best in Europe. Little over a decade ago, pressure on the hospital service was such that patients in A&E departments were regularly kept on trolleys for hours in draughty corridors awaiting admission. In 2002, the Association of Community Health Councils, the then patients’ watchdog, reported that a 71-year-old woman with a broken hip had waited 40 hours for admission to Northwick Park Hospital in London. Such shocking treatment is unimaginable today, where a wait in excess of four hours, the present target, is, rightly, regarded as unacceptable.

But these improvements have been forgotten in the few short years since they were achieved. Today, once more, the talk is only of crisis.

It is true that the challenge the NHS currently faces – how to deal with a £30bn projected deficit by 2020-21 – is extremely serious. But it is not insuperable.

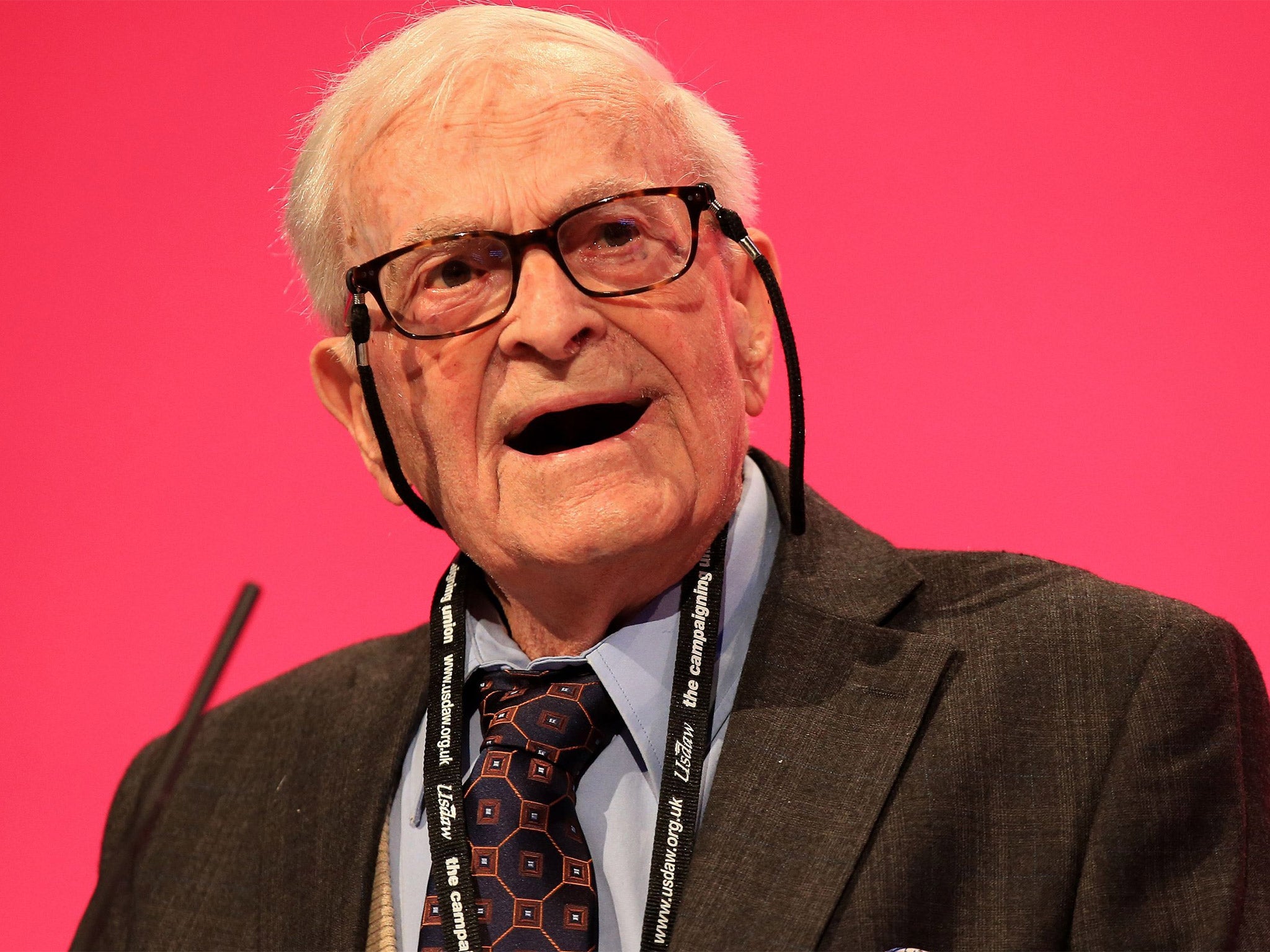

Harry Leslie Smith, the 91-year-old campaigner, last month took the Labour conference by storm when he warned of the danger of returning to the “barbarous, bleak, uncivilised time” before the NHS when “public health didn’t exist”. Yet that is what may happen if we do not properly appreciate the value of the jewel in the welfare crown.

As a £113bn business, the NHS has grown by over £60bn since 2000. Cash was poured into the service so fast during the latter years of the Blair government that the NHS could not spend it fast enough. That undermined reform. It proved easier to do the same, but more of it, than to do it differently. Productivity has fallen by an average 0.2 per cent a year.

Now it faces an unprecedented financial squeeze. The upside is that a squeeze can provide the spark to efficiency improvement. A patient who gets the right treatment at the right time in the right way enjoys better care, spends less time in hospital and saves money. The NHS thus faces a stark choice – become more productive or make significant cuts in services.

The truly remarkable feature of the last decade is that despite the extraordinary expansion in NHS capacity – millions more operations and patients treated, thousands more doctors and nurses – it has not been enough. Demand has risen even faster and with budgets now curbed, the service is at a crisis point. If we carry on the way we are we will not cope.

The “factory model of health and social care”, as Simon Stevens, NHS chief executive, recently put it, churning out more services to heal the sick, will not meet the challenge presented by rising rates of dementia, obesity and chronic disease and growing patient demand for a swifter, more personal, more convenient health service.

Stevens described how to provide care at nights and weekends the NHS had grown a “chaotic, complex, Heath Robinson service” of 999 calls, 111 calls, urgent care centres, A&Es and GP out-of-hours services that cause “mass confusion”. Services must be redesigned to support those in need, respond efficiently to emergencies and ensure swifter intervention to prevent ill health, curbing the flow of patients at source.

These are among the key challenges the NHS faces. Is it worth saving? In August, the Commonwealth Fund compared the healthcare systems in 10 countries (France, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the US, Canada and Australia) and rated the NHS the best overall. It was ranked top for safe, effective, co-ordinated, efficient, patient-centred care.

Not bad for a 66-year-old.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments