Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In February 2002, when the Scottish lawyer Olivia Giles began to feel odd at work, she thought little of it. Her first concern was how she was going to deal with the pile of paper stacked up on her desk. Little did she know that, within hours, her illness would develop into something extreme that would alter her life for ever.

It started on a Thursday afternoon. Giles, then 36, had been out of the office at a meeting and was anxious to get back and get on with her work. But she was cold, she was shivery, and she was taking her eye off what she was supposed to be doing. She decided to go home early.

Events took a turn for the worse. "I remember getting out of the car door and not having enough concentration, and falling out on to the drive," she says. "When I managed to get into the house, I was actually shaking with cold. I put the heating on full, got into bed with my winter coat and rolled myself up in the duvet. I relaxed, and by midnight had changed into pyjamas. But it was a very uncomfortable night. I was panicking about the work I hadn't done. I kept waking up and it was the itch in my hands and feet that was getting to me."

In the morning, her partner noticed she wasn't well and the couple decided to call in a doctor. The following afternoon, on the arrival of a locum medic from her local surgery, her fears were only partly allayed. Although she later found out that she had contracted meningococcal septicaemia, a serious disease in which the meningococcal bacterium multiplies rapidly in the bloodstream – causing blood poisoning – she was only tested for meningitis at this point. Conducting tests for meningitis, while it is caused by the same bacterium as meningococcal septicaemia, would not have shown a positive result (because the bacteria infect a different part of the body in each disease). Later, the information from a correct test could have been used to help Giles; but by this point she was already well on the way to being critically ill.

She continues: "Walking to the door to let the doctor in, my body just wasn't responding to what I was asking it to do. I had difficulty opening the latch because my fingers weren't gripping properly. She didn't look at my feet, which I was complaining about. I told her about the itch and she said my hands were red because I had been scratching them.

"I know now that she did do some tests for meningitis, but I didn't have meningitis. I thought I had glandular fever because my glands were very swollen and that's because of the septicaemia. I asked her to take a blood sample, which she did with quite bad grace. It disappeared, unfortunately, because it would have given a good indication of the stage at which the disease was.

"She told me to stay in bed and take aspirin. I told her I thought I was iller than aspirin. She said, 'If you're not happy with what I'm doing, you should go to hospital.' And I thought, 'Well, I obviously don't need to go to hospital and be a hypochondriac,' and that was that."

Giles went to sleep, but was still suffering from a persistent itch in her feet. She peeled back her socks to scratch, and, to her shock, saw that her feet were covered in purple blotches. There were similar marks on her hands – some like pinpricks, others bigger.

"I didn't know what it could be. I didn't know a single thing about meningitis. I did ring the surgery and spoke to the locum and asked for an ambulance. And she asked whether I could drive myself, which I thought was outrageous. At that point, I couldn't function at all.

"When the ambulance came, it took me ages to get myself to the door. It took me so long that the guy was about to drive away, but fortunately he saw me. He actually carried me from the door into the ambulance, and then realised he couldn't treat me on his own. So when the second ambulance came we set off to accident and emergency. There was a huge commotion; I was just lying there thinking there was obviously something really wrong with me. I heard someone say the word meningitis. Someone else said toxic shock. It didn't sink in that I was hours away from dying."

Giles entered a coma on 22 February 2002, and did not wake up for another month. During this time, the meningococcal bacteria had to be treated by antibiotics. But the disease had taken hold. During its course, it causes the patient's blood vessels to haemorrhage, and blood circulation does not reach the extremities of the body, such as the hands and feet. In Giles's case, oxygen was prevented from getting to her limbs, and the result was gangrene. This gangrene began to spread up her arms and legs and over her elbows and knees.

It was at this point that her family had to make a choice – let Giles live with a quadruple amputation above the elbows and knees, or let the gangrene take its course. But, at exactly the time they chose the latter, her plastic surgeon arrived to examine her X-rays. He resolved that there was some chance of saving most of Giles's knees and elbows. In the knowledge that it might not work out, four separate amputation operations went ahead, and the doctor managed to save all her knees and elbows. "What I have left is heavily skin-grafted. My knees are not in a great state but they function and have functioned for five and a half years," she says.

Giles spent eight months in hospital. By the time she left, she had been fitted with prosthetic legs. "The moment of realising that I was able to walk, there was relief and joy. Knowing I was going to walk out of that hospital on my own two legs was life-changing."

Each year, 1,500 to 1,800 cases of meningococcal disease – which includes meningococcal septicaemia – are reported in the UK. Many people who get meningococcal disease make a full physical recovery, but about 15 per cent are left with severe and permanent disabilities.

Giles is positive about her situation, saying that there is little she can't do physically. "I don't have the same energy I used to have, but I don't know whether that's because I am almost six years older. I can walk, and often people don't know I have prosthetic legs. I don't wear prosthetic upper limbs; it's amazing what you can do with biomechanics, but it doesn't come close to replicating the function of a hand. In fact, if you have elbows you can do an awful lot with stumps."

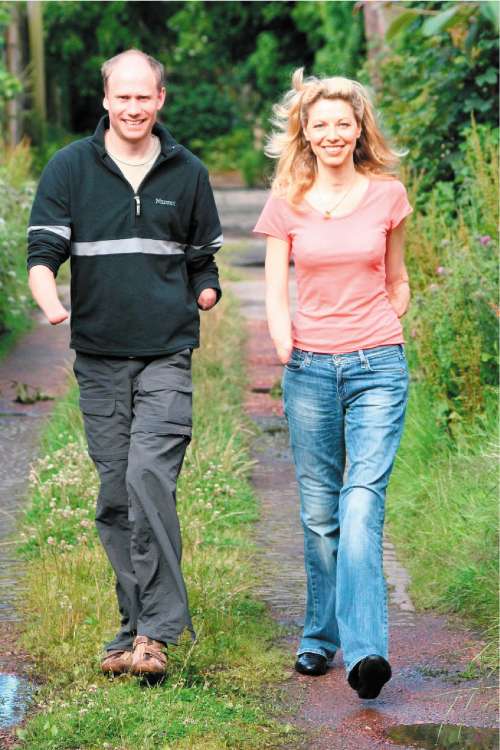

After this harrowing experience, Giles has set up the charity 500 Miles, with fellow quadruple amputee Jamie Andrew, to support people who have gone through similar experiences. They aim to fund initiatives that "will deliver prosthetic services and related care in areas of desperate need", including paying for the education and training of prosthetists, funding components for prosthetic limbs or building prosthetic centres. Part of their work focuses on the need for prostheses in Malawi and Zambia. Last year, Andrew, who had a quadruple amputation in 1999 after suffering frostbite as a result of a mountaineering accident, took part in a triathlon to raise £50,000 for the charity.

Giles says: "There is something dignifying and humanising about being able to stand up and walk. I was taking it for granted from the NHS when I was asking what kind of legs I could get; it never entered my head that I would be left as a broken thing that couldn't move. But, in many places in the world, that is the consequence. You see pictures of what people have cobbled together for themselves out of leather, or tin cans. If the money was there, somebody could buy a limb, a below-knee prosthesis, for £65. Think how lightly we would spend £65. That would be enough to give someone a second chance like the one I had.

"If I'd ever read a meningitis leaflet, even if I had it in my subconscious, something would have registered because I had all the symptoms. I just didn't know anything about the disease. I genuinely think if I had had a clue in the past I might have thought to have a look at the internet; or, if I had kept the leaflet, I would have been able to look at it.

"Now, my philosophy is that if you see an opportunity to do something, if you really see it, if you think, 'Gosh I could do that,' you've got an obligation to do it because you've only got one shot."

For information on 500 Miles, see www.500miles.co.uk. For information on meningococcal septicae-mia, see www.meningitis-trust.org

Walk with me: how the world is helping amputees

* Lower-limb amputations are carried out worldwide every 30 seconds, but only about one-third of amputees who lose a lower limb will walk again. Part of the reason for this is the shortage of prosthetic limbs in the developing world, where it is thought that about four million people need lower limb prostheses because of illness or accident.

* In the UK, the NHS provides prosthetic limbs to all amputees. But, in many developing countries, there's a lack of expertise in the prescription and fitting of prosthetic limbs and orthopaedic braces. In Senegal, West Africa, there is only one foot clinic for the country's 12.5 million inhabitants.

* Reasons for needing prostheses include landmines, and diseases such as polio, cerebral palsy and leprosy. Apart from 500 Miles, charities helping those in need of prostheses include Handicap International and the International Committee of the Red Cross.

* According to the Seattle-based Prosthetics Outreach Foundation, a below-knee prosthesis be as simple as a plastic foot linked to a custom-fitted plastic socket. Prosthetic knees made from aluminium are available for above-the-knee amputees.

* Prostheses such as the widely available Jaipur foot, which has only two parts, can be provided in the developing world for as little as $30 (about £15), compared to $8,000 for comparable limbs in the US.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments