'I began to starve myself...'

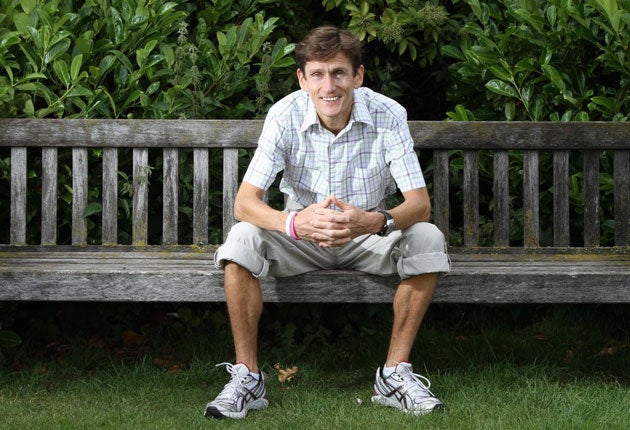

For 25 years, Ian Sockett had anorexia – until a life-threatening infection gave him the wake-up call he needed. He describes how he fought back from the illness that's affecting growing numbers of men

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As I lay in my hospital bed, I'd never felt so scared or alone. I glanced at my painfully thin body, emaciated by 25 years of anorexia. At 5ft 7in, I weighed five stone. After years of surviving mainly on coffee and fruit salad, while continuing to push myself to exercise almost every day, my body couldn't take any more.

I had pneumonia, a collapsed right lung and was in urgent need of a blood transfusion. I was also in isolation so, although I desperately wanted to see my parents, I couldn't. The seriousness of my situation hit me for the first time. I knew I might die in this room, alone.

To explain how I found myself in this dark place, I need to go back 25 years, to a very different time. I was 15, a top-grade student tipped to be the next head boy who represented the school and county in athletics, rugby and cricket – I was the Midlands 400m champion. Life was great. My parents and teachers had high hopes.

Then my beloved grandmother, or Nana as I knew her, died of an aneurysm. I'd been very close to Nana – my brother Andrew and I used to stay with her and granddad when my parents were at work. While Granddad was quite a strict disciplinarian, Nana was softer and spoilt us. Losing her was my first experience of death, and of losing anyone close. I was devastated but I was also confused. I couldn't accept that the rest of the world was continuing as though nothing had happened. Didn't anyone realise my Nana had died? I felt my life had come to a grinding halt.

I don't know why I didn't talk about my feelings. But I kept thinking that maybe this was what it was like for everyone, and how could I burden my mother with this when she'd just lost her mother?

I realise my reaction to the situation was peculiar, but maybe not as uncommon as you might think. I rationalised that if I was physically hurting, this would somehow make the pain of losing Nana easier to deal with. I could not justify being happy and carrying on as if nothing had happened.

So, quite simply, I began to starve myself. Slowly at first, but maintaining the same level of sporting activity. My body started to hurt when I ran but I was determined, no one was going to stop me. And so the pattern began. Once you start to starve yourself you find you can manage to exist on smaller and smaller amounts. You soon learn the calorific content of everything.

My running was one of the first things to suffer. I no longer had the energy to perform at the same level. This made me angry but I couldn't stop, even though I had a constant gnawing pain in my gut. I couldn't accept that I wasn't as good as I used to be and this made me angrier and more miserable.

By the time I took my A levels, I was on the hamster wheel of self-punishment, driving myself harder while existing on fewer and fewer calories. I was no fun and didn't want to go out, so inevitably friends stopped asking me. Soon, there were no friends.

Studying gave me the perfect excuse to shut myself away in my room, too busy to eat at mealtimes. I was amazed when a tutor suggested I apply to Oxford – I was just Ian Sockett from the local secondary school in rural Herefordshire. I passed the entrance exam and went for the interview, but I didn't want to go to university, by now my life had imploded. I didn't get accepted and when the rejection letter arrived it confirmed what I already knew – I was no good.

I got a local job in sales and marketing but my parents were extremely worried about me. Eating disorders are difficult for the sufferer but perhaps even more so for family and friends, who can't understand why someone won't eat. I eventually agreed to seek professional help, but back then the thinking around anorexia, especially in men, was hardly advanced.

The experience felt horrific. I was referred to what most people would call a psychologist, who asked if my parents had sexually abused me. I was disgusted. He was talking about the only two people who hadn't given up on me, who'd cried rivers of tears watching their son disappear before their eyes. I left feeling sickened. I did not go back.

By 2007, I was holding down a professional job with the local authority, and working 11-hour days at M&S at weekends. This seven-day routine had been going on for almost three years, and was another form of self-punishment – why should I let myself enjoy my weekends? I weighed less than six stone, I always felt cold, rarely laughed and was a truly frightening sight.

By now I'd got used to people staring, even though it hurt. I heard people whispering, they assumed I had cancer or Aids. None of those applied to me. The reason I didn't have a girlfriend was simple – I looked hideous.

For men, things are exacerbated because admitting to having an eating disorder isn't macho. People think it only affects teenage girls responding to messages from the fashion industry. This isn't true. I knew exactly how I looked; there was no body image deception. I hated what I saw and detested having my photo taken. Anorexia was a way of self-harm, of punishing myself.

My wake-up call came the following year. I caught a chest infection and when two courses of antibiotics failed, I was admitted to hospital. I began 2008 being told I had pneumonia and my right lung had collapsed. The doctors kept me in as they wanted to "hit me hard" with intravenous antibiotics to try to control the infection.

During my first afternoon, the hospital closed to visitors to contain an outbreak of norovirus, or the winter vomiting bug. Hours later, due to taking antibiotics, I got the runs. I was placed in isolation over fears I had contracted the virus. I found myself alone, stuck within four walls and banned from seeing anyone. I felt weak and soon became very, very afraid. My mum was outside, left to imagine what was happening.

I was so frightened that it suddenly dawned on me just how precious life really was. I realised I might never leave the hospital. Despite feeling very weak, alone and terrified, I'd already made my decision. I was going to get out of this dreadful situation and do something to repay society for all those wasted years. It may sound strange, but I started to formulate my goal. I'd fulfill my childhood ambition of running a marathon. I'd make my parents proud of me again. I knew it wouldn't be easy, but those same traits of bloody-mindedness and determination would help me win the greatest battle of my life.

I decided to run for Macmillan Cancer Support. I'd started fundraising for them while at M&S and one thing that had stayed with me was how Macmillan was there for everyone affected, not just the individual but family and even friends. Sometimes we just need someone to give us a hug, hold our hand or to be close. Lying alone in hospital, I empathised with how important that was.

The journey back to health and marathon fitness was long, frustrating and difficult. You don't change a 25-year way of thinking overnight. You're in a routine, you think, "what's going to happen if I change that and do something different?" But I started eating three meals a day, and the sky didn't cave in and nobody died. This enabled me to keep going. I also needed to put on weight slowly – too fast could have caused my heart to overload and internal organs to fail.

There were plenty more tears. I kept thinking, "I'm never going to make it". But I knew I couldn't let anyone down. My greatest motivator was the thought of completing a marathon, hanging that medal around mum's neck and saying, "Thanks for being there". I'd also been accepted to run for Macmillan, and I owed them a debt of gratitude for believing in me. Plus, it no longer hurt to run, I could really put some power behind it. Food became fuel for me. I didn't want any therapy or professional support. Besides, very little was available in my area.

My first marathon was Paris 2009. The residing memories are the pain in my quads during the last few miles and the words "Go, Soko, go" yelled by one of the Macmillan support team, balanced precariously up a French lamp post.

I did it, I completed my first marathon. And I've not stopped since. I'm 41 and I do some form of exercise every day, either running, swimming or going to the gym, and I weigh about nine stone. I've raised more than £10,000 for Macmillan.

I've run the London Marathon twice, each year beating my previous time. I completed this year's in three hours, 13 minutes and 55 seconds, which gave me automatic qualification for 2012.

Of course, I wish I could turn back the clock 25 years and start again. But while I might have wasted those years, I've been given a second chance and I don't intend to waste one minute of it.

I'd love to meet a woman now and have a relationship – I'm on the market with a big "for sale" sign. I know I'm probably quite naïve; it would be my first proper relationship for a long, long time. But I feel I have a lot of love to give.

For me, having a reason, or several reasons, to recover from anorexia was pivotal. What's important to remember is that no matter how deep a hole you've dug yourself into, there's always a way out. I'm living proof.

Interview by Linda Harrison

Eating disorders: not just a female problem

* The number of men with eating disorders is rising, according to the Royal College of General Practitioners. Doctors report a 66 per cent rise in hospital admissions of men for eating disorders over the past ten years.

* An estimated 1.6 million people in the UK suffer from an eating disorder, and around one in five is male, according to the eating disorders charity Beat ( www.b-eat.co.uk, helpline 0845 634 1414).

* Anorexia in men often begins with excessive bodybuilding or exercise, or specific occupations, including athletics, dance and horseracing.

* The charity Men Get Eating Disorders Too ( www.mengetedstoo.co.uk) states that men are most likely to develop eating disorders between the ages of 14 and 25, but it can happen at any age.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments