The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

How does alcohol cause cancer?

Aine McCarthy of Cancer Research UK explains the link between alcohol and seven cancers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a cabinet in London’s British Museum nestles a 5,300 year-old wedged-shaped tablet called a cuneiform. On its surface is scrawled one of the earliest forms of written language in the world.

And it’s a record of Mesopotamian workers’ beer rations.

Clearly, humanity’s relationship with alcohol stretches back thousands of years, but a long relationship doesn’t necessarily mean a healthy one.

We know that alcohol is damaging to our health in a number of ways. And the one we’re most concerned about here at Cancer Research UK is its impact on cancer risk.

We’ve written about the link between alcohol and cancer many times before – from discussing the evidence that it causes cancer to talking about how drinking less reduces your risk of developing the disease.

But we haven’t yet explored the science behind how alcohol affects and damages our cells, and how this can cause the cells in our bodies to develop into cancer.

Which cancers?

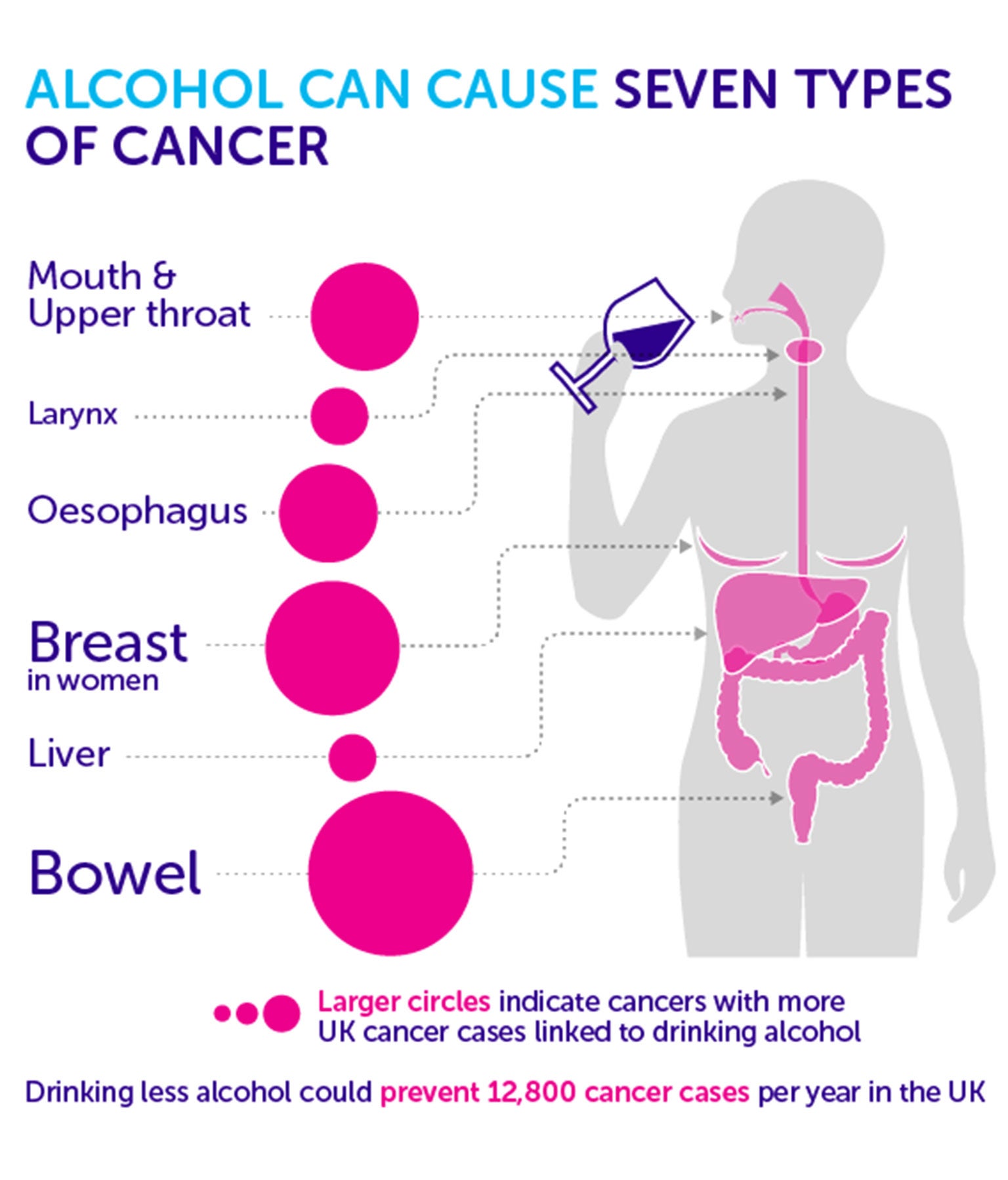

There are seven types of cancer linked to alcohol – bowel, oesophageal (food pipe), larynx (voice box), mouth, pharynx (upper throat), breast (in women), and liver. There’s also mounting evidence that heavy drinking might be linked to pancreatic cancer. But how, and why?

According to Dr Ketan Patel, a Cancer Research UK expert on how alcohol causes cancer: “We don’t really know. We don’t fully understand why alcohol causes some cancers and not others.”

There are some theories, however, although some are stronger than others.

The best evidence we have is for mouth and throat cancers where alcoholic drinks directly damage cells in these tissues.

And, because alcohol also increases a person’s chances of developing a scarring of the liver known as cirrhosis, it’s thought that this increases their chances of developing liver cancer.

There’s also some evidence that certain bacteria in your mouth and throat – and maybe even in the bowel – could be involved in alcohol causing cancer. But the link isn’t clear and we don’t know for sure, so we need to wait for more data.

And, as we will briefly discuss below, there’s good reason to think that alcohol’s effects on hormone levels might be behind its link to breast cancer.

While there may be a perception that the health risks of alcohol only apply to heavy drinkers, research is revealing that it’s not just drinking large amounts of alcohol that increases your chances of developing cancer – drinking small amounts can be harmful too.

Although there’s a lot we still don’t know about how alcohol is linked to different types of cancer, researchers are starting to figure out at least one of the ways that it causes harm.

A nervous breakdown

Like most things you eat or drink, alcohol – be it in a pint, shot or cocktail – gets broken down by your cells.

In the case of ethanol – the chemical name for the alcohol we drink – it ultimately gets broken down to create energy.

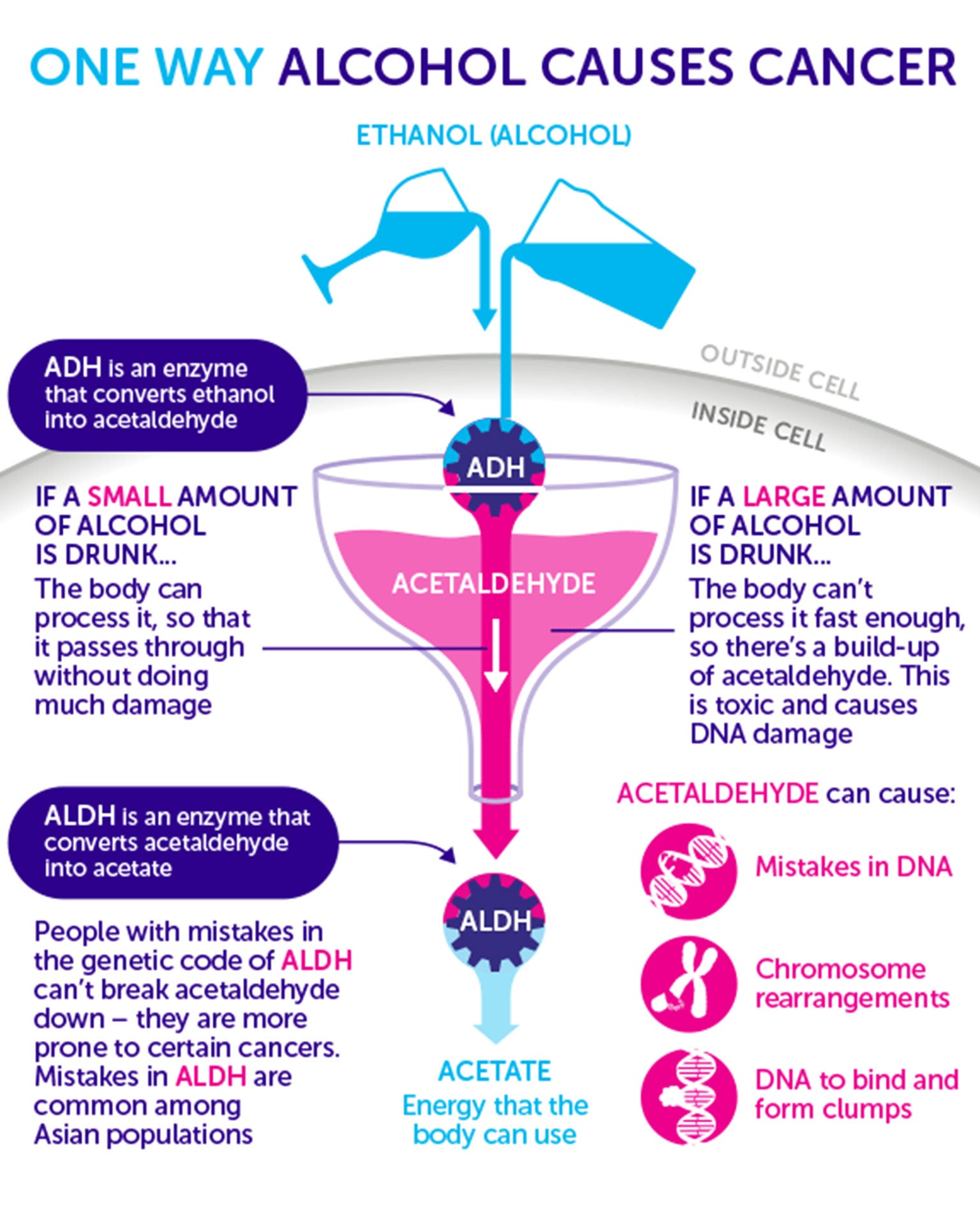

First an enzyme called alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) converts ethanol to another molecule – acetaldehyde. This then gets broken down by a second enzyme, acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), into acetate, which our cells can use as a source of energy.

This is a relatively straightforward process, and one that evolution has equipped our bodies to handle with ease. So where’s the harm in having a drink or two?

Ketan_Jayakrishna_Patel_FRS

Dr Ketan Patel Image via Wikimedia Commons CC-BY-3.0

The risk lies with the middle man – acetaldehyde.

“Ethanol itself is relatively non-toxic other than the consequences of drunkenness,” says Ketan Patel. “It doesn’t directly damage DNA. But as the body breaks it down, it goes through a step where it is converted to a highly reactive, toxic chemical called acetaldehyde.”

“And it’s a build-up of this which likely causes changes that lead to cancer.”

To prevent acetaldehyde building up and damaging DNA, human cells contain three ALDH enzymes – ALDH1A1, ALDH2 and ALDH1B1, which rapidly break down acetaldehyde into acetate. This means that acetaldehyde doesn’t usually have time to build up or hang around for long enough to cause significant DNA damage.

But this protection mechanism can be overwhelmed once alcohol is in the bloodstream, meaning it doesn’t work properly.

What’s more, it isn’t available to everyone. Some people have mistakes or changes in the genetic code of their ALDH enzymes which cause them to malfunction, so acetaldehyde can build up. In turn, this leads to DNA damage.

“It’s known as the flushing mutation” says Patel. “It’s particularly common among Southeast Asian populations – for example, up to 70% of the Taiwanese population have it.”

“People with mutated ALDH enzymes become flushed in the face and very often feel very sick after drinking alcohol.”

Thankfully, our cells contain a further layer of protection, in the form of a variety of ‘toolkits’ that can repair damaged DNA (which we’ve discussed at length in this post).

But both of these systems have their limits, so damage can still happen.

“Most organisms – from bacteria to humans – have these two protection systems. But if you overwhelm them they won’t work,” says Patel. “That’s when you get acetaldehyde causing DNA damage and changes that lead to cancer.”

Mutations and rearrangements and clumps….

This is an important part of the chain of evidence linking alcohol to cancer risk.

“The evidence that mistakes in DNA can lead to cancer is overwhelming,” says Patel.

So how exactly does acetaldehyde affect our cells’ DNA? Over the years, scientists have identified several forms of damage.

DNA ‘spelling mistakes’

Acetaldehyde can cause errors in DNA called point mutations. These are a type of mistake where one base – or ‘letter’ – in a gene is swapped for another. And because DNA is the instruction manual that tells our cells what to do, mistakes in it can lead to cancer.

Rearranging the furniture

Acetaldehyde can also trigger larger-scale changes to our DNA, by messing up entire chromosomes (the technical name for the long strings of DNA in our cells). It can cause bits of chromosomes to break off and to swap around, meaning genes end up in the wrong place and don’t work properly – these are also phenomena that can trigger cancer.

DNA clumps

Acetaldehyde has also been shown to bind to DNA, forming clumps called adducts. These play havoc with how DNA works, folds, replicates and repairs itself. Essentially, adducts are another type of mutation, and they too can cause cells to become cancerous.

The cup runneth over

So far we’ve seen that alcohol can be broken down into a harmful chemical – acetaldehyde. We’ve looked at the systems in place to prevent it damaging our DNA. And we’ve looked at the sorts of damage it can cause.

Now let’s take a closer look at what’s going on when we have a drink or two. To visualise how alcohol overwhelms our cellular defences, imagine you’re pouring alcohol – say red wine – into a glass through a funnel.

If you only pour a small amount into the funnel, the wine will flow right through.

But if you continuously pour the alcohol into the funnel, without taking time to stop or pause, the funnel will overflow.

Similarly, too much alcohol stops the ALDH enzymes and DNA repair pathways from working properly, so the systems become overwhelmed, resulting in a build-up of acetaldehyde, and damage that can lead to cancer.

While this neatly explains why certain cancers – such as bowel and liver tumours – are linked to heavy drinking, what’s more of a mystery is why other forms are linked to much lower levels of consumption.

For example, we know that light drinking increases a person’s risk of developing cancers of the upper aero-digestive tract, namely mouth, upper throat and oesophageal cancers.

One theory that might explain this is the bacteria we mentioned earlier. It’s thought that the bacteria in our mouth are very good at converting ethanol into acetaldehyde, resulting in a very high level of acetaldehyde, even if only a small bit of booze is drunk.

Clearly there’s a lot more work to be done to really understand how the ‘funnel’ idea plays out in different tissues of our bodies, and just how much (or little) alcohol can cause it to ‘overflow’. As well as why some forms of cancer are more strongly linked to alcohol than others.

But as well as acetaldehyde causing DNA damage, there are other ways alcohol can lead to cancer too.

Other potential mechanisms

Smoking is the number one preventable cause of cancer. So it’s not surprising that if someone drinks and smokes, they’re increasing their chances of developing cancer even further. But for some cancers, it seems that these two effects in combination are much worse than either by itself. Why?

The interaction between alcohol and smoking is complex. Acetaldehyde is also a by-product of burning tobacco, as is a second, similar chemical: formaldehyde.

But to go back to our funnel, if you drink and smoke there’s more chance of creating an overflow because the body’s systems can’t work fast enough to handle the damage caused by both of them at the same time.

“If you smoke and drink, you’re going to have a greater build-up of acetaldehyde and other toxins, which will increase the damage to your DNA and, in turn, your chances of developing cancer.”

As well as this, there’s also evidence that alcohol can make it easier for the cancer-causing tobacco chemicals found in cigarettes to get into tissue and cells.

Alcohol increases a woman’s chances of developing breast cancer – but how and why this happens still isn’t fully understood.

One theory is that drinking alcohol affects women’s hormone levels, increasing the amount of oestrogen in the body, which is then used by breast cancer cells as fuel for growth.

But it’s not necessarily straightforward to unravel. Lots of other things affect oestrogen levels, including whether the woman is pre- or post-menopausal, the stage of her menstrual cycle and whether she’s taking hormonal contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy (HRT).

Patel is cautious. “We know alcohol increases women’s risk of developing breast cancer. But so far, the exact mechanism that causes this increased risk hasn’t been pinned down,” he says. “At the moment, the evidence is too weak to say for definite how alcohol causes breast cancer.”

“We need more research to figure out this complex cause-and-effect relationship.”

More or less?

Research is slowly revealing more about how alcohol causes cancer, and the theories we’ve discussed in this post are the ones with the strongest supporting evidence.

But there are other ideas that haven’t yet been fully explored or resolved. These include changes in folate metabolism, increased production of reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species and the role of bacteria in how alcohol is metabolised.

At Cancer Research UK, we’re committed to finding out more about the mechanisms by which alcohol causes cancer.

We’re continuing to fund Dr Patel’s research, which is focusing on how alcohol is broken down into different chemicals in the body and how this can damage cells and trigger cancers – particularly liver cancer. He is also studying both the long and short-term effects of exposure to alcohol.

And one of the big questions raised by our Grand Challenge funding scheme is asking if the mutational fingerprints left behind by lifestyle factors like drinking alcohol can help us better understand the link between environmental factors and cancer.

But no matter how alcohol causes cancer, one thing is clear.

The best way to reduce the risk of cancer from alcohol is to drink less of it – whether that’s by having more alcohol-free days every week, swapping out some glasses of booze for soft drinks during a night out, or picking lower strength drinks or smaller servings.

The relationship between humans and alcohol goes back millennia and it’s an integral part of many societies’ social lives. Of course, adults have the right to decide how much they want to drink, but alcohol’s health impacts are undeniable. By working with the Government, policy-makers and healthcare professionals, we’re aiming to raise awareness of the risks of alcohol and help people make choices that can reduce their cancer risk.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments