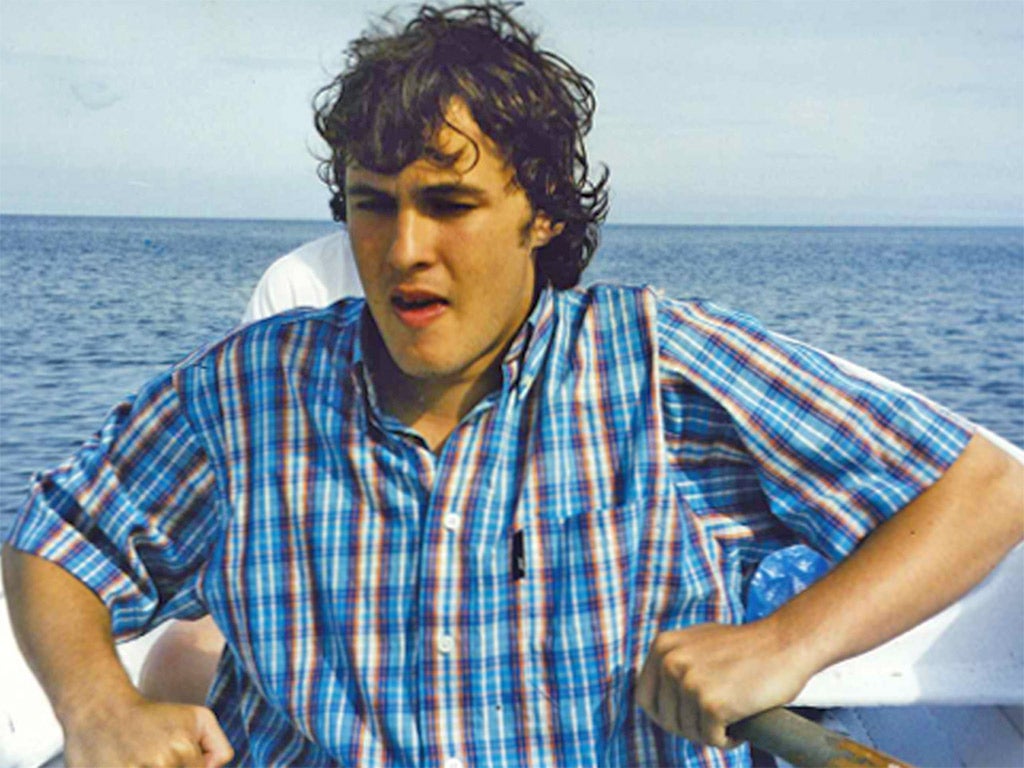

Henry Cockburn: If I say I'm schizophrenic people reply, 'So you've got a split personality'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I am quite open about my illness and people generally are more interested than afraid of it. I remember that before I was diagnosed as a schizophrenic in my teens I did not know much about it.

I thought it meant someone who would flip out at the most trivial of things. Other people are often equally ignorant. Since my recovery, I have gone back to Art College. I told some of students that I was a schizophrenic and they said “Oh, do you have a split personality?” I don’t know if it was a good idea telling them this because they are young and impressionable.

Stigma is what people think about others and, to a degree, I say to myself: “who cares what they think?” But I should care because I entered the system as I didn’t conform to the norm, though you could also say I was a danger to myself so that I needed to be locked up. People are afraid of madness because it is the unknown. Mental hospitals are shrouded in stigma and I had never been in one until I was sectioned. I remember once walking out of my hospital, and taking the back route which passes through a council estate. I heard a six-year-old shout at me “get back to the hospital”. It got me really down that day.

Violence on the ward was a brutal way of settling scores. I got in a few fights but I would not say I was violent person. Once there was a bloke with a titanium head in my ward. He said that he had fallen off his motorbike on Friday the 13th a year earlier and had broken his skull. One day I threw a potato chip at him and it landed on his head. He went mad and punched me until the staff came to break it up. I am surprised there weren’t more fights. If you take a lot of unstable people, a few with violent tendencies, and coop them up 24 hours a day for week after week the outcome is inevitable.

It is unfair to connect violence with schizophrenia and other mental afflictions. Only a small minority of mentally ill patients are violent and this may not be related to their illness. One man I knew in the ward was a racist. He took four pool balls, put them in a sock and swung it at an African patient, bashing him on the head. This racist incident was isolated and didn’t happen again. Another time a Rastafarian, who was a religious fanatic, threatened to hit me because I said I didn’t believe Mary, the Mother of Jesus, was a virgin.

The reason I was in the most secure ward of the hospital was not because I was violent, but because I was an escape hazard. The most violent thing that happened in my ward took place a couple of months before I arrived. Two people had committed suicide in their rooms: One had burned himself to death and the other had hung herself.

I had a friend called Toby when I was in a less secure ward in hospital. I was 20 and he had been in the sixth form at school. We used to play hacky sack, a game where you have a small ball full of beans like a juggling ball. The object of the game is to kick the ball and not let it fall to the ground. Toby used to play the guitar. I had known him before he was in hospital when he was into drugs in a big way. I walked into town with him once and we went to a park where where I rapped while he beat-boxed (making the rhythm). He thought kids were laughing at us, but I reassured him that they thought we were good.

One day I got in late to the hospital and I was called in to the staff room; I thought I was in trouble because I had been spitting out my medication. In fact it was much worse: Toby had committed suicide. He had jumped in front of a train. I knew that he used to cut himself, but I didn’t quite know how depressed he must have been. It hit us pretty hard on the ward.

Violence is only one small component of mental illness. People are afraid of it because they don’t know what it is. They are told by the media that schizophrenics are dangerous violent people who should be locked up, though it is much more complicated than that. Some people suffer from hallucinations and delusions and it is up to the doctor to decide if they are mad. You can say you hear the voice of God and be considered sane, but if you say you hear the voices of dogs or trees they question your mental health.

For me the decision was that my behaviour had gone beyond eccentricity into madness. I became very introverted and wary of electrical objects, thinking they could tap into my thoughts. I would go for days hiding in trees and bushes completely naked, and sometimes I did this in the snow. I would plunge into ice-cold lakes or rivers. I could hear trees and bushes talking to me, but I never hurt anyone.

Schizophrenia: The shame of silence, the relief of disclosure

The stigma of the hidden schizophrenia epidemic

Editorial: We are failing sufferers of mental illness

Henry Cockburn: I like to be liked – and finally I’ve found friends who really like me

Is this the 'tobacco moment' for cannabis?

Henry Cockburn: 'I can hear what other people can't'

Fashion advice from the shrink’s sofa

The demise of the asylum and the rise of care in the community

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments