Freud's collections and 'The Unconscious': How a new show of his antiquities helps us to understand him and ourselves better

To mark the centenary of 'The Unconscious', the psychoanalyst's collection of antiquities will be on show at his old London home as Freudian scholar Benjamin Poore explains

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Collecting is a way of trying to stay in control of things. Just ask the Duke in Robert Browning's dramatic monologue "My Last Duchess". "That's my last Duchess painted on the wall," he tells us as we wander around his art collection, "Looking as if she were alive." As the poem unfolds, we learn that the Duke had his wife murdered because he suspected her of flirting with other men, and put her in a painting in his collection, behind a curtain, because that was the only way he could quell his murderous rages.

But the painting, in a rather unnerving move, has the last laugh. The Duke perceives in his companion a strong, perhaps even erotic, attraction and sympathy with the "depth and passion" of his late wife's "earnest glance" in the picture. And this only serves to rekindle in the Duke the anger that the painting was supposed to quiet in the first place. The bride waiting downstairs, we suspect, will surely become part of the collection, too.

When you try to arrange matters, Browning's poem seems to say, they can arrange you. Or as the author Hunter Davies, who has written extensively about his collections of Beatles' memorabilia and old tax discs, puts it: "You don't really start collections, collections start you." Davies is especially alive to the compulsive, almost pathological, character of the drive to accumulate: "I have lots and lots of doubles and triples," he writes, "I don't know why I want them – it's a sickness, a madness, an obsession." We collect all sorts of things, for mystifying reasons: I have hundreds of old train tickets and theatre programmes which I never look at; a friend of mine keeps a list of every lover she's ever had. Rod Stewart is keen on model trains.

A hundred years ago, Sigmund Freud published his essay "The Unconscious", and his ideas (like those of the psychoanalysis he invented) are not generally regarded as terribly cheerful. Freud suggests, for instance, that family life circles back and forth from murderous wishes to sexual impulses; or when discussing the unconscious, that we are constantly working to sabotage what we think of as our own best interests. As the writer Adam Phillips put it in his recent biography, Freud "shows us how ingenious we are in not knowing ourselves".

Yet, just as psychoanalysis can reveal the deepest aspects of the human psyche, so can a collection – and it is both fitting and fortunate that Freud was a keen collector. He collected nearly 3,000 antiquities of diverse kinds over the course of his life – statuettes of Greek, Roman and Egyptian gods, Assyrian fertility statues and, of course, plenty of phalluses – and in their own way they evoke the most primitive and unreconcilable parts of the human mind. If the 'id' – in German, das Es, "the It" – is a metaphor for the most deeply buried and prehistoric parts of the self, then Freud's collection provided the opportunity for his patients to stare his in the face.

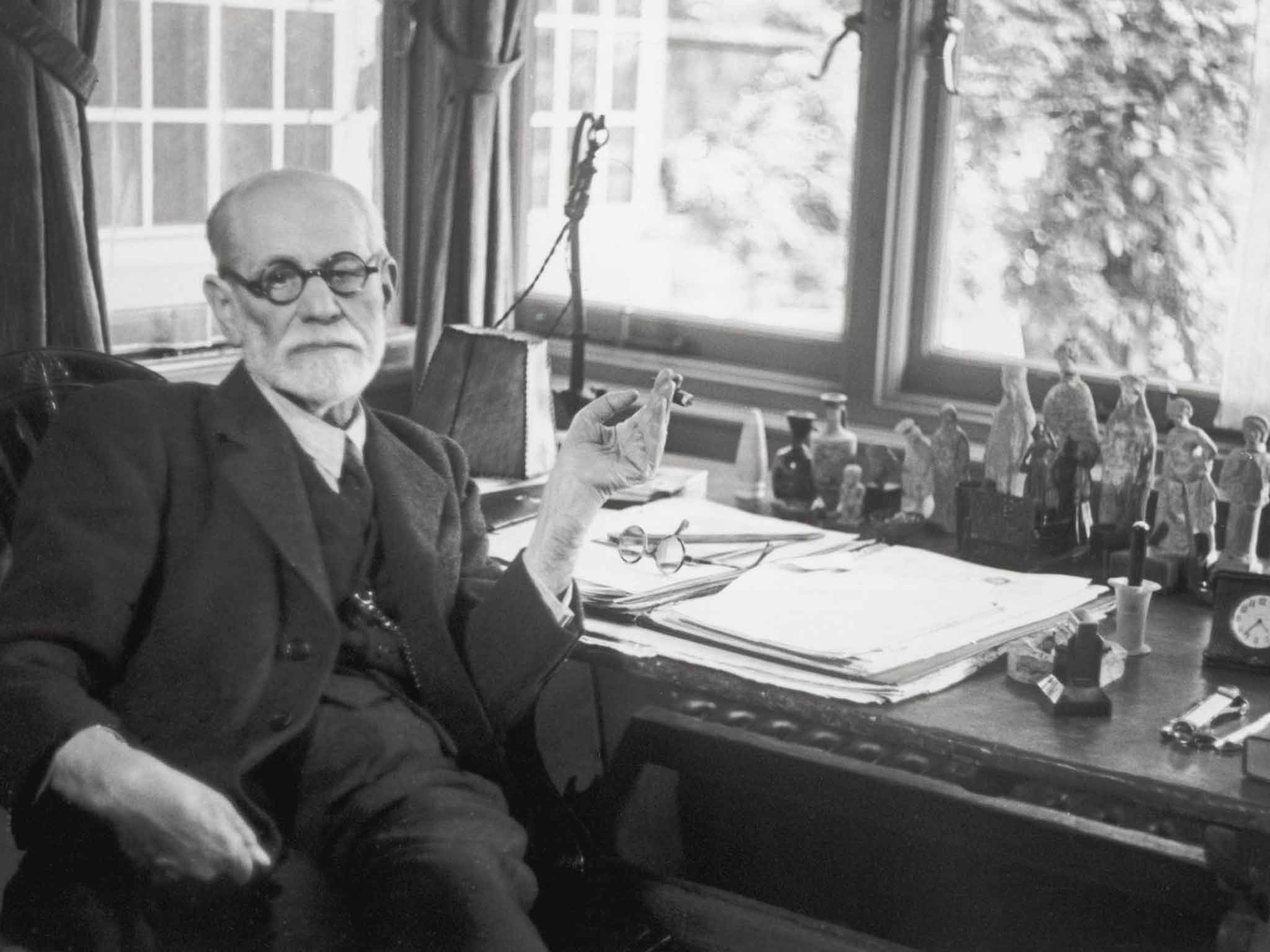

What Freud collected tells us a lot about how he saw himself as a professional – suggesting new ways of understanding his thought – and this summer, there will be a chance to get up close and personal. To mark the centenary, the Freud Museum in London will be running "The Festival of the Unconscious", offering visitors the opportunity to experience artistic and intellectual responses to Freud's work through installations, talks and a replica psychoanalytic couch for visitors to try out – and allowing them to see his collection as his old patients once did.

Among their number was the American poet Hilda Doolittle, who mentions the collection in the memoir of her treatment with the psychoanalyst, Tribute to Freud. In her account, she often returns to the treasures Freud arranged in a semi-circle on his desk – which prompt her to further reflections on the nature of psychoanalysis and its attempts to unravel and decode the psyche. How do psychoanalysts know what is "real" or meaningful in our dreams or fantasies, and what is not? For Doolittle, the collection provides an analogy: "We can discriminate as a connoisseur (as the Professor does with his collection here) between the false and the true… there are priceless broken fragments that are meaningless until we find the other broken bits to match them."

In particular, she describes how Freud shows her a carved, ivory Hindu statue of Vishnu, sparking an encounter, and a reflection, both enigmatic and intimate. The detail on the statue reminds Doolittle of a trip to Greece, yet the "extreme beauty of this carved Indian ivory" makes her feel "a little uneasy… [it] compelled me, yet repulsed me, at the same time". For the poet, these objects opened up the whole question of her relationship to the Viennese doctor analysing her. "Did he want to find out how I would react to certain ideas embodied in these little statues?" she wonders. "Or did he mean simply to imply that he wanted to share his treasure with me – those tangible shapes before us that yet suggested the intangible and vastly more fascinating treasures of his own mind?" Freud's collection might help him to do his job, drawing out her unconscious thoughts and conflicts; or it allows Freud to show off to her, rather grandiloquently and narcissistically, how mysterious and fascinating he is himself. In either case, the collection is the first stop on what Freud called, in the context of dreaming, "the royal road to the unconscious".

But what does Freud's collection – these symbolic objects, dug up from the past – reveal about him? What can we make of his fascination with archaeology, and especially the 19th-century archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann, who claimed to have discovered and excavated the ancient city of Troy? Freud would come to identify the work of the psychoanalyst with that of the archaeologist, excavating away the layers of the conscious mind to find the ruined palaces and streets on which our mental lives are ultimately founded: the buried traces of memories and desires that linger on in our psychic lives. In his famous case of the "Wolfman", a patient haunted by a childhood dream of a pack of wolves, it is reported that Freud said to his client: "The psychoanalyst, like the archaeologist in his excavations, must uncover layer after layer of the patient's psyche, before coming to the deepest, most valuable treasures."

Freud's work offers descriptions of dreams, slips of the tongue, half-recovered memories, flashes of unconscious fantasy. In this way he builds a collection of the artefacts, the excavated treasures, of our internal world. Walking around Freud's study, with thousands of artefacts bearing down on you, isn't so different from taking a wander around the psyche. And perhaps this is why Freud's collection appears obliquely in The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, from 1903 – the text that introduced the concept of the "unintended action", or "Freudian slip", to the world. "A slip in reading that I perpetrate very often when I am on holiday… is both annoying and ridiculous: I read every shop sign that suggests the word in any way at all as 'Antiques'. This must be an expression of my interests as a collector." In a sense, the book is itself a sort of collection – of anecdotes, of second-hand stories – that, while it is chatty and informal, is at the same time a serious attempt to put in order what we normally regard as trivial: slips of the tongue, mis-spellings, a dropped pot or stubbed toe. True, they are homely and bourgeois – but they are private, too, committed behind closed doors. And it is what goes on behind closed doors that psychoanalysis is interested in.

Freud's contemporary, the philosopher Walter Benjamin, felt collectors to be of special interest because they represent the poles of order and disorder which are characteristic of modern urban existence. The collector, Benjamin writes, "takes up the struggle against dispersion" and is "struck by the confusion, by the scatter, in which things in the world are found". The modern world – exemplified in shopping centres, underground trains, bombed-out cities, crowds of refugees – is a cacophony, and the collection is modernity's tuning fork. The unruliness of the internal world that Freud described is something we all intuit today, but he was the first to see it as a reflection to the sound and fury of early 20th-century European life, regularly punctuated by technological, political and social upheaval. For him as for Benjamin, then, collections are attempts to guard ourselves against being swept away by the tumult. And this was a tumult that Freud would experience first hand, with his collection as witness: it was only catalogued when the Gestapo came to call to ascertain its value after the Anschluss in 1938.

Freud, being Jewish, fled from Vienna in 1938 so that he might die in freedom in London. And the collection, which followed shortly after, played an important role in the final stages of his life. When he arrived, according to his first biographer Ernest Jones, great efforts were made in the display of the collection: "His son Ernst had arranged all pictures and the cabinets of antiquities to the best possible advantage in a more spacious way than had been feasible in Vienna." As for Freud's desk, the family maid Paula Fichtl knew the collection so well that she was able "to replace the various objects... in their precise order, so that he felt at home the moment he sat at it on his arrival". Freud's collection allowed him to feel at home when he was displaced. It even played a talismanic role. A bronze statue of Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom, was the mascot for his emigration. "We arrived proud and rich," Freud wrote in a letter, "under the protection of Athena."

However, the thing about collections is that they are never finished, and adding something new changes the way everything else looks. (As Walter Benjamin wrote of the acquisitive type, "his collection is never complete; for let him discover a single piece missing, and everything he's collected remains a patchwork".) Freud was, in the tinkering manner of a collector, endlessly editing and supplementing his earlier books with footnotes, asides and new observations. His three most famous books – Interpreting Dreams, The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, and Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious (if it's not one thing, then it's your mother) – are among the most heavily revised of all his texts, with Freud making emendations decades after their publication.

Collecting is key to Freud's understanding of how we come to be the people we end up as. "The character of the ego," he writes in The Ego and the Id, "is the precipitate of abandoned object-cathexes… it contains the history of those object choices." Behind the rather bloodless language lies something more disturbing. Our sense of ourselves – the "I" that we each imagine ourselves to be – is made up of all the people and things we have once cherished and then lost or abandoned. Your identity is the accumulated heap of lost love objects. Which is to say, if you were to wander around your psyche, it might look rather like a room stuffed to the gunnels with dusty old artefacts, some tarnished, and now unloved, some recently rearranged, or polished; rather, in fact, like Sigmund Freud's study.

'The Festival of the Unconscious' at the Freud Museum, London, opens on 24 June

A bit of fluff

Librarian Graham Barker holds the Guinness world record for the largest collection of belly-button lint. Having worked tirelessly at navel gazing since 1986, Barker has now amassed 22.1 grams of his own body fluff. The uses for such a collection are obviously endless: Barker himself has considered using it to stuff a cushion.

Need for 'Speed'

A hoarder in Idaho has set himself the challenge of collecting every single VHS copy of the 1994 Keanu Reeves cult classic Speed. Ryan Beitz says that his pursuit first began when he was broke and trying to find Christmas presents for his family. They all ended up getting copies of Speed on VHS, of course, the lucky things.

Live-in dolls

Mechanic Bob Gibbons, has collected over 240 love dolls which, alongside his wife, Elizabeth, reside with him at his home in Herefordshire. Made of rubber and silicone, Gibbons admits that he finds them attractive, but says that he's never, er, used them. The collection of blow-up dolls is apparently worth more than £100,000.

Feeling clucky?

A couple from Indiana own more than 6,500 chicken-related items. Joann and Cecil Dixon have spent the past 40 years forming their collection, which ranges from chicken-based ornaments to chicken fridge magnets. No prizes for guessing what they're having for dinner tonight.

Quiet, please

Swiss businessman Jean-Francois Vernetti has collected more than 11,000 "Do Not Disturb" signs from hotel doors across the globe. He's been at it since 1985, when he found one sign that was spelt wrong and decided to start collecting others as a joke. He must be desperate for a good night's sleep.

Clowning around

Much was disconcerting in BBC2's Meet the Ukippers, broadcast in February, but nothing more so than former press officer Liz Langton's collection of nearly 2,000 porcelain clowns. Perhaps the implicit suggestion was that Langton was ringmaster for this particular circus (a frustrating task, going by the mounting gaffes shown in the programme).

Benjamin Poore and Harriet Agerholm

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments