Father's Day 2014: Portrait of a Slack Dad: Dispatches from the frontline of wayward fatherhood

He ignored the pregnancies, had little time for his young children, and was asked to leave the family home. Yet, on Father’s Day, Nicholas Lezard reveals that the wayward dad has much more to give his offspring than lonely lunches in Pizza Express

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As Larkin put it in his most famous poem: man hands down misery to man; that's the bad news. Here is the good news: man can also hand down kindness. By "man", of course, we, and Larkin, mean, mainly, "father". The mother's kindness is generally understood; or, to look at things another way, her unkindness more aberrant. Fathers are, or used to be, the Old Testament God: deep but unspoken love, punctuated, as in a summer storm, with lightning flashes of rage. This was fatherhood as I understood it, on its receiving end, before the whole business about the New Man and the father who would weep as he held his newborn child in his arms, declaring his pride at his achievement. Ignoring, as he did so, the minimal and ignominious degree of his responsibility so far.

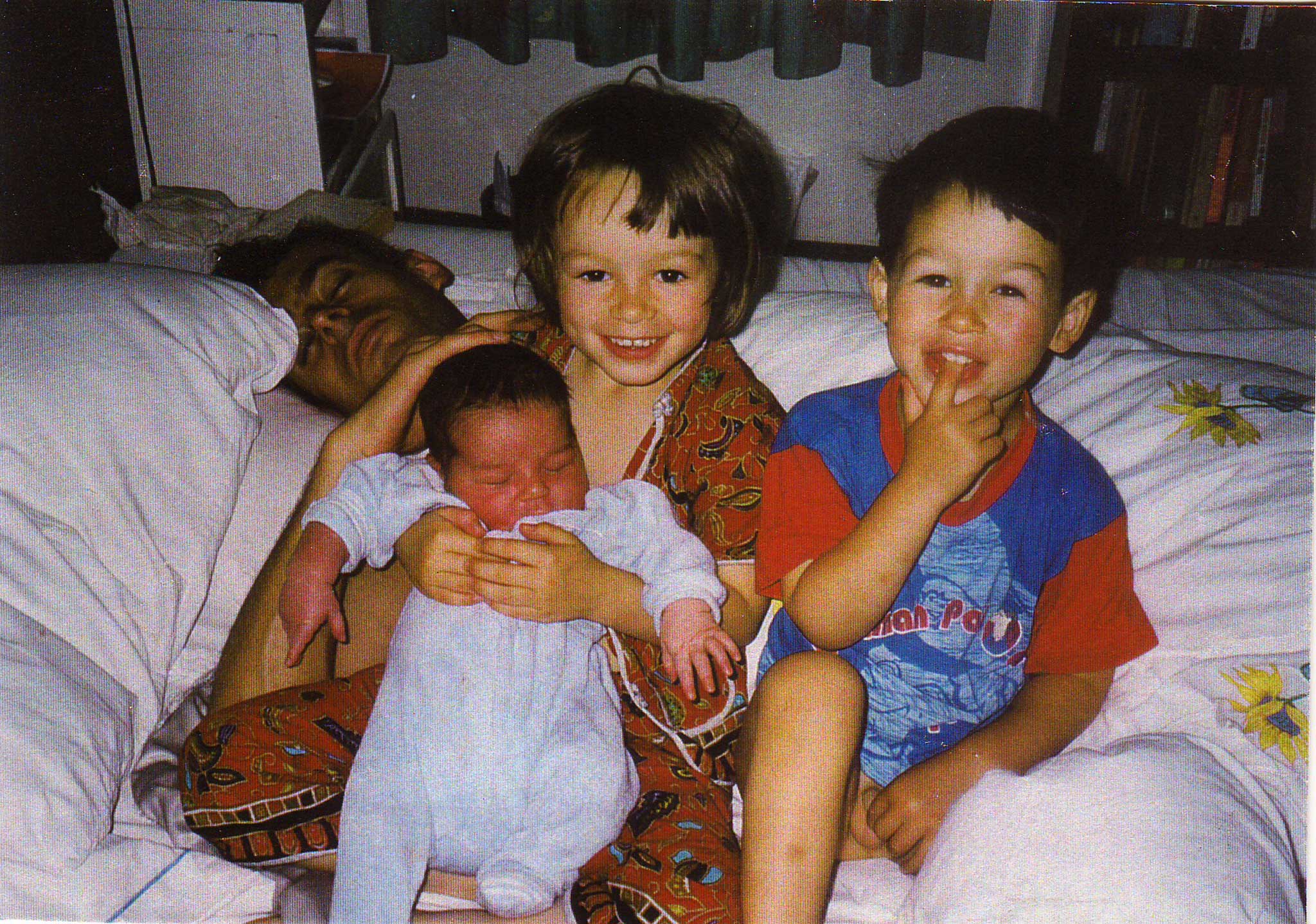

For me, fatherhood was never part of the plan. I swept the news of each successive pregnancy under the mental carpet, but after three children arrived, it became impossible to ignore them. (Actually, I already had an inkling, because sex, sleep, and predominantly dark hair had become swiftly-receding-into-the-distance memories.) The best way to do something about the crisis of patriarchy, as I saw it developing before my very eyes, was to monetise it, but I had no idea how to do this until one day The Guardian, whose family-pages editor at the time was inclined to mischievousness, suggested I write a piece from, for a change, the reluctant parent's point of view; and so, towards the end of the 1990s, Slack Dad was born. (There have been others who have pinched this title, but I coined it.)

Slack Dad took as his premise the concept that fatherhood was difficult, dangerous and, most importantly, something that went against millions of years of natural selection. Working from home, Slack Dad did not expect to get away from the various baby-related chores that the modern man was expected to deal with; but he didn't want to be emasculated either. The principles I drummed into the children were: don't bother me unless it is absolutely necessary; read lots, and try to be smarter than me.

Which was all very well, until one day, with the children ranged in age between six and 12 years old, I was invited to leave the family home, on a permanent basis. This was unpleasant for any number of reasons, but one of the most unpleasant was that it meant that I would only be seeing my children on alternate weekends. From Slack Dad to Sacked Dad. Actually, in my case, it worked out rather more often than that, as I was invited to pick the youngest up from school every weekday and look after him until at least the eldest got back (their mother worked office hours); but even that had its pains, as I found myself visiting, on a daily basis, the house from which I had officially been exiled.

This changes everything. Learning the ropes of fatherhood was hard enough when your boots are on the ground, in the territory. There's no getting around this: you only learn how to be a father from your own father. Which is, because your father never sat you down and taught you, pretty much the same as having to come up with your ideas yourself. But at least you have some experiences you can draw on. My father, for instance, would call me "stupid boy" in the manner of Captain Mainwaring chastising Private Pike in Dad's Army; I couldn't use the same phrase with my children, as they didn't then know the programme; so I used the adjective "wretched", when affectionate rebuke was needed. The mother didn't like this, but the children got it; the middle one even toyed with the idea of a superhero costume with a big W on the front, and creating "the Adventures of Wretched Boy". But now I was the wretched one (the word comes from the Old English wrecca, meaning "exile", or "outcast". More on this in a bit.)

So, for me, learning how to be a fortnightly father was something completely new. For one thing, I had actually come to love my children. I was with Montaigne on the notion that he couldn't understand why some fathers love "children scarcely born, having neither motion in the soul nor form well to be distinguished in the body whereby they might make themselves lovely or amiable".

My children were, I had come to the conclusion after a combined total of 28 years of keeping half an eye on them, or, to put it another way, a combined total of 14 years keeping both eyes on them, lovely and amiable, in soul as well as form, and now, just as they were getting interesting, I was being asked to take my leave. I had always pitied those womanless men you saw dining at Pizza Express with their children; the men looked harassed and borderline suicidal; the children resentful at having to lift the mood of this man whose sudden absence from the family home was having consequences they could barely yet comprehend, with results they could not imagine. You could see the children mentally putting aside some pocket money for future therapists' bills. I resolved not to be that man: so the first decision I made was to get our pizzas from the supermarket, and eat them in front of the telly. (More on this later.)

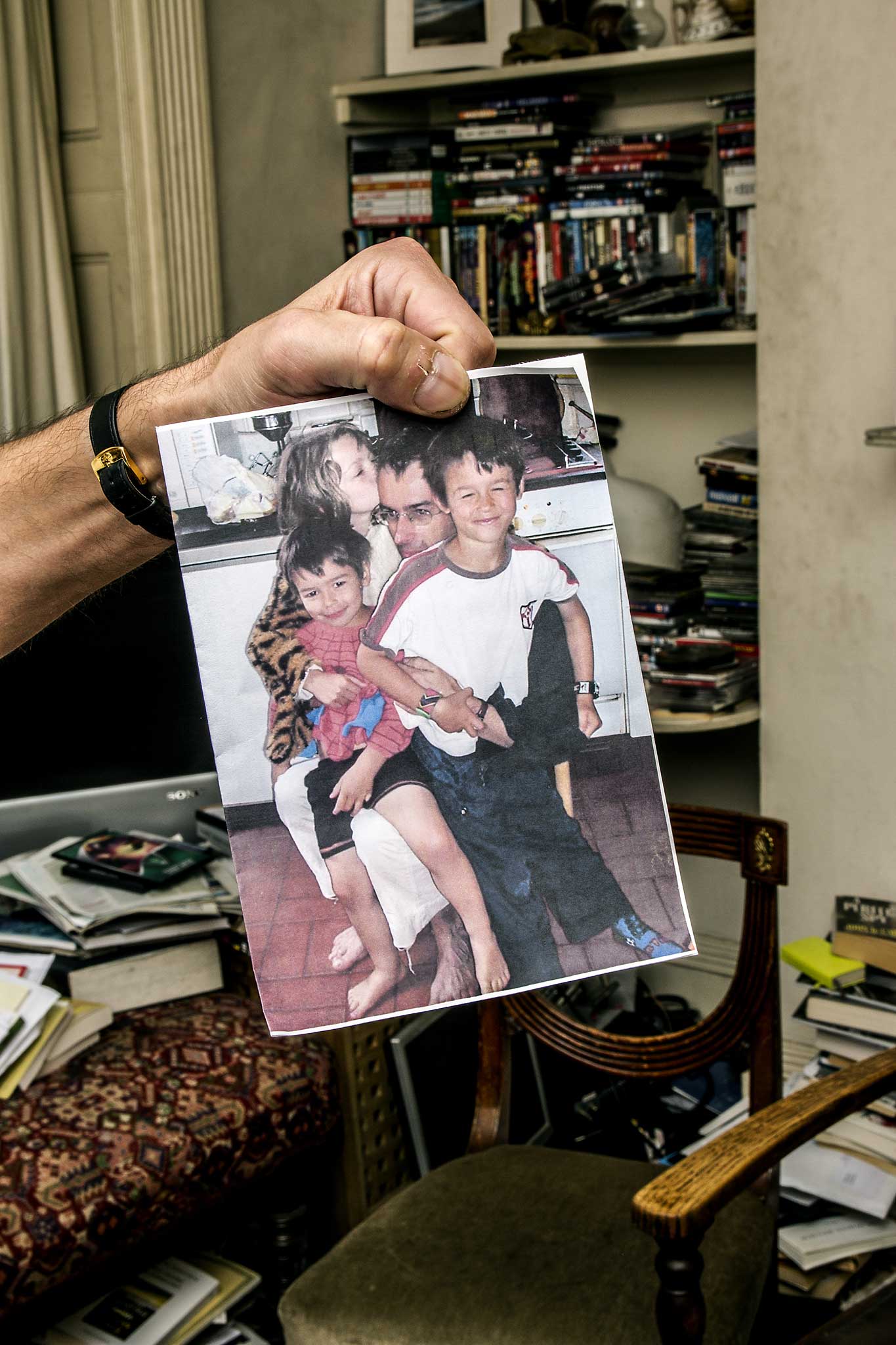

But the very interesting thing was how being Sacked Dad actually intensified the experience and nature of fatherhood. I have become a strange mixture of a not-quite father (ie not there all the time) and the pure essence of father (by virtue of not being there all the time, and therefore sullying an idealised concept with boring incessant demands to tidy rooms, practise musical instruments, do homework, make me tea, etc, etc). There's that ease that distance can convey; coupled with the mutual assurance that the ties are deep, strong, and transcend all distance. I am a place they can bolt to at a moment's notice should things get sticky in the maternal home. (Which is not to cast aspersions on their mother, who has never even remotely toyed with the idea of restricting my access to the children, which is pretty much rule Numero Uno for not screwing up the children.)

And I think, touch wood, that things are turning out OK. I remember an eye-opening moment some years ago, when I read Socrates's line that acting as if you are brave is, actually, and for all practical purposes, exactly the same thing as being brave; and I think this principle can be extended: acting as if you're a good father is the same thing as being one. And this becomes so much easier as the children grow up, and the adults nearest them cease to be demented with insomnia and the stresses of the new task that has been thrust on them.

How one acts as a good father is, of course, a problem that's not much different from how one might actually be a good father, but I would say that among the essentials are a combination of authority and anti- authority, by which I roughly mean Not Being Their Mother. I once saw a sign in a park in Gothenburg which told me that in April, female moose reject their one-year-olds and leave them to, so to speak, stand on their own four feet, which comes as a sudden and cruel surprise to the young ones; humans would do well to consider this as an alternative parenting strategy. The mother's love is always there, unbudgeable; the father casts a sterner eye, the suggestion being that love and respect are, to a degree, earnt, not handed out willy-nilly by your father.

Except: of course they are handed out unconditionally. This notion of there being no unconditional love from fathers is nonsense, a rhetorical flourish and a trick we pull to get our children to behave well. I would keep this to yourself, though. There is, however, a certain volatility that is acceptable in a father: a tendency to fly off the handle for what might appear to be no immediate reason, or to react to minor setbacks with a highly disproportionate degree of outrage. It is important to keep one's children on their toes in this respect, and to remind them, if not in so many words, that their existence did not come about just because of an overwhelming broodiness, but also because their fathers were more or less ordered to insert Object A into Slot B. (Incidentally, and as you might have guessed, I have left all the business of explaining the facts of life to their mother, and the internet.) "I have three children and no money," wails Homer Simpson in one inspired moment; "why can't I have no children and three money?" I remember watching that episode with the children, and saying, "That's not actually funny," while giving them a hard glare.

But here is the real secret. The point is that we were watching the show together. And it was a cartoon. The thing is that, as The Simpsons acknowledges, the father is actually a child, too; he's just a big kid who wants to play with his toys, and there lies the true connection with his children. It is no accident, I think, that my own father would shout to me and my brother, with as much excitement as I do to my children, to hurry up and sit down because Doctor Who is about to start; that programme's function as a family uniter has been acknowledged, but never as fully as it deserves to be, in my opinion. (Not that I or my brother or my children ever needed to be told when the next episode of Doctor Who was on. The point was that my father was telegraphing his own delight, and his complicity with ours.)

For the Doctor himself, and in his varying incarnations, is about alternative modes of fatherhood. And so when I started encouraging my children to nurture the belief that I might in fact be from Gallifrey myself, and therefore not fully subject to the laws of conventional human society – eccentric, wilful, liable to disappear at a moment's notice but to save them from monsters when it mattered – it was a delusion they were happy to connive in. "Walk around as if you own the place," David Tennant's Doctor advised a new companion when she asked how to fit in upon landing in a strange culture; again, the notion that pretence is as good as achievement, sometimes.

So here is the wonderful thing: I would seem to have escaped the fate of many fathers of teenage children – to be considered a boring, irrelevant buffoon. And they have escaped the fate of having fathers who think their children have somehow failed. I remember thinking, before all this fatherhood thing happened, that fatherhood might just about be acceptable if it turned out that my children were smart, and loyal, and good, and happy, but not mindlessly so; and it turns out that (touch wood again) this would indeed seem to be the case.

The pizza-eating Saturday evenings we would spend watching the films that I think make up the canon of cinema history (lots of Hitchcock, etc); this has translated into one of the children wanting to study film-making. The others, too, like to pop round to my rather messy home (I teach them that there are virtues besides which tidiness is an irrelevance) and stay there for a while; and they still like it when I call them "wretched". For, as I have since learnt, the word may have come from one whose original meaning was "outcast"; but, by extension, it came very soon afterwards also to mean: "knight errant", and so "adventurer" and "hero". A bit like a certain Time Lord, now I come to think of it.

The dad files: Nicholas Lezard's fatherly advice

1. Don't be a hypocrite. And don't think you can get away with double standards. Children smell that a mile off.

2. Be gender-neutral. They know whether they're boys or girls. No need to nudge them in either direction.

3. Be age-neutral. While bearing in mind at all times their capabilities, plant the idea of Getting On With It Themselves whenever you can.

4. Don't be needy. Don't demand love, or respect. I've seen parents who do this, and it's quite revolting, frankly.

5. When they outsmart you or answer back with a frustratingly viable objection, respect them. You might even go so far as to applaud them.

6. Be funny. Almost always. It's grim out there; no need to make it grimmer.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments