Digestive disorders: Is your stomach trying to tell you something?

With an alarming rise in all manner of digestive disorders, the condition of our insides is turning into a first-world crisis. What’s causing it, asks Siobhan Norton - and how is it solved?

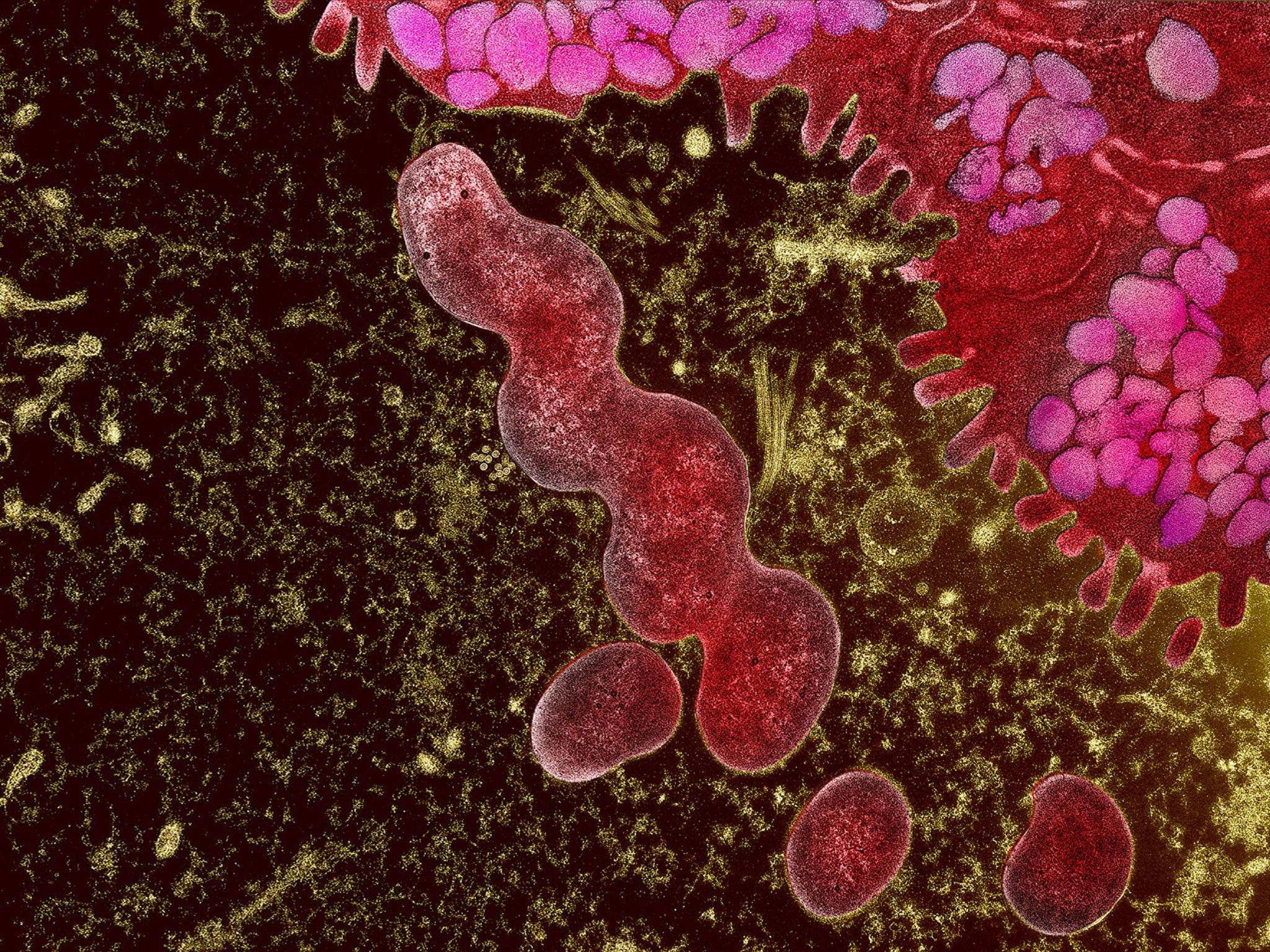

No man is an island, they say. But even the biggest recluses among us are never alone – we are all, in fact, outnumbered. From the moment we are born, our bodies are colonised by other organisms – a vast population of microbes setting up home on our skin, inside our mouths and noses, and in our gut. So much so that only 10 per cent of the cells in our body are human cells.

It should come as no surprise then, that how our bodies work is less of a dictatorship and more of a democracy. All the bacteria living within our body have to co-operate to help things run smoothly and prevent civil war. This isn't for free, of course. We feed the hungry little buggers – and in return they help to break down our food and convert it to energy, provide essential enzymes and vitamins, and regulate our immune system. The problems arise when the wrong kind of food helps the troublemakers to flourish at the expense of our healthy, helpful "good bacteria".

So far, so yoghurt commercial. But scientists now say that the microbiome – the collected microorganisms – in our digestive system is more than a mulching factory for food, but in fact the "second brain" – which may be just as important as the first brain in our heads. Perhaps we already know this to some extent – we associate the gut with raw, instinctive emotions and reactions. Gut reactions, even. We know that if we're stressed or anxious, this will be the first place we show symptoms of it, which makes sense. In times of fight or flight, the body will shut down its energy-sapping digestive processes to allow the energy to be diverted elsewhere.

A persistent problem nowadays, experts reason, is that we are in a constant state of stress or anxiety, so our gut never gets the chance to do its job properly. A 2011 study in Brain, Behaviour and Immunity suggested that stress alters the structure of the microbiome. A 2012 study indicated that, in turn, gut bacteria can affect our stress responses.

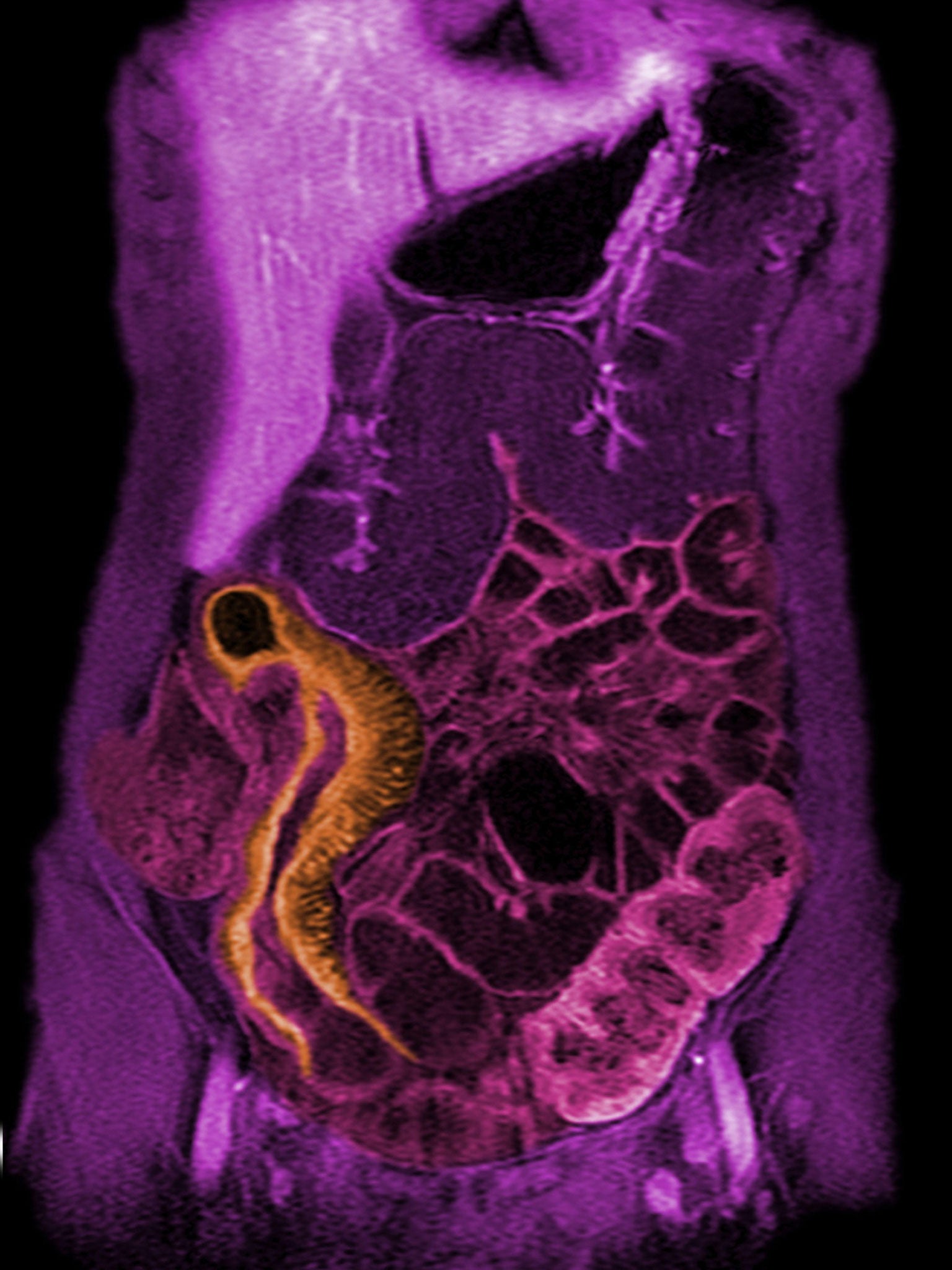

There is no denying that some very modern maladies are on the increase. Irritable bowel syndrome, that spectrum of general digestive unpleasantness, afflicts an estimated 10 to 20 per cent of the UK population. More serious, perhaps, are the inflammatory bowel diseases like Crohn's and ulcerative colitis. A 2012 study published in the journal Gastroenterology indicated that inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) are emerging as a global problem. Incidences are far higher in Europe and North America – although there is considerably less data from developing countries. Autoimmune diseases such as lupus, coeliac disease and type 1 diabetes are also on the rise. Between 2001 and 2009, the incidence of type 1 diabetes increased by 23 per cent, according to the American Diabetes Association. And, of course, there's the No 1 Western problem – obesity.

Why, then, is there such a growth in certain diseases in the West? Some say that we are quite literally navel-gazing – a poor man working on a factory line in Hanoi has little time to moan about an upset tummy. Or is our diet – high in sugar, processed foods and artificial ingredients, while being refined and low in fibre – causing serious damage to the delicate symbiosis of our microbiome?

One emerging theory behind the imbalance is the hygiene hypothesis. This goes straight back to – you guessed it – our gut. We are exposed to bugs from the second we are born, quite literally, as our first brush with bacteria will be from the mother as we emerge from the birth canal. Studies suggest that children born by caesarean section don't get this initial burst of bacteria, and may have a weakened immune system as a result.

Similarly, as children grow up, they get dirty, put things in their mouth, kiss the dog, and essentially do lots of things to expose themselves to bacteria. But when we get trigger-happy with the Dettol and load up on unnecessary antibiotics, there is far less exposure. Of course, hygiene is good, and antibiotics have prevented far more diseases and premature deaths than they could cause. But our immune systems could be so coddled that they can't withstand the first threat of real infection.

Professor Tim Spector believes that most of the microbes in our systems are crucial for good health, but that our modern lifestyles have upset the balance. "We start life with a weakened biodiversity," he says. "The tendency towards caesarean sections, overclean environments, reliance on antibiotics, lack of fibre and a less diverse diet all contribute to a deranged microbiome."

In his book The Diet Myth: The Real Science Behind What We Eat, Spector looks beyond calorie-counting to how the food we ingest is really fuelling us, and how our gut bacteria could be influencing that – and vice versa. He conducted an experiment with the help of his son, Tom – their mini version of the documentary Super Size Me. Tom lived off a diet of McDonald's for 10 days, giving a stool sample before and after. In the short time period, the junk food had dramatically reduced the diversity of his microbiome by 40 per cent, and replaced "good" bacteria with those that can cause inflammation.

Dr David Perlmutter is another champion of the "gut brain" – and believes an imbalanced microbiome could be causing everything from Alzheimer's to autism. He has worked with patients suffering from various conditions, including Tourette's and multiple sclerosis, and claims they have seen dramatic improvements with an altered diet or procedures such as faecal transplants.

"Some of my most remarkable case studies involve people changing their lives and health for the better through simple brain-making edits to their dietary choices," he writes in his book, Brain Maker. "They cut carbs and add healthy fats, especially cholesterol – a key player in brain and psychological health. I've watched this fundamental dietary shift single-handedly extinguish depression and all of its kissing cousins, from chronic anxiety to poor memory and even ADHD."

Spector is slightly more cautious. "We are making real progress, but people don't realise how young this field is," he says. "When it comes to illness, we need much more research to discover whether a disordered microbiome is causing problems or simply making them worse. For instance, autistic children have abnormal microbiomes, but they also tend to have abnormal diets."

It is certainly a complex area to study – a handful of soil contains more microbes than there are stars in the sky, Spector says, and our bodies contain 100 trillion of them, weighing more than 4lb in our guts alone. However, he says that he can tell if someone is healthy simply by examining their microbiome – and he has examined plenty.

He is part of the British Gut Project, the UK arm of the American crowdfunding effort to get a major sample of the population's bacteria. The project has been appealing to the public for donations – monetary and faecal – to help them gain more understanding of the geographical, dietary and genetic differences in people. In return for a donation, participants get a breakdown of their microbiome, but no dietary or medical advice is given on the back of it. It may seem like an impossible quest – Spector admits Britons are sensitive about poo – but the project has been attracting about 100 volunteers a month, with 1,300 participants to date, to go with more than 3,000 in the US.

Spector believes that in the future a better understanding of the microbiome could lead to personalised diet advice. "Some people can eat meat without any ill-effects. Some people react differently to pasta, or lentils. There is even a 'skinny bacteria' – there have been tests on mice involving Christensenella. When the bacteria was transplanted into their microbiome they gained less weight."

Perhaps, then, the ultimate question is how to maintain a balanced microbiome. In his book, Perlmutter outlines his ideal diet to boost bacteria. It is rich in probiotic fermented foods like kimchi and sauerkraut, unprocessed meat and vegetables and (the good news) dark chocolate and red wine. Spector follows a similar regime. "I have cut out all processed foods – but have more coffee and dark chocolate." He says we need to think of our microbiome like a garden – we need to nourish the soil (intestines) for healthy plants (bacteria), while minimising weeds (disease-causing microbes). "It's important to remember that you are never dining alone – you are with your microbes."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments