Confessions of a bad parent

<b>Simon Carr</b> had to raise his sons alone. His no-rules approach resulted in chaos - and inspired a major British film. But did it work?

Every family is happy in a different way, so how do we know what to do for the best? There is no Unified Theory of Parenting. Some children with all the advantages become drug addicts; others are brought up by wolves and go on to run merchant banks.

The underlying fact is, we do what we can. Or, to resist generalising (that won't last), I did what I could.

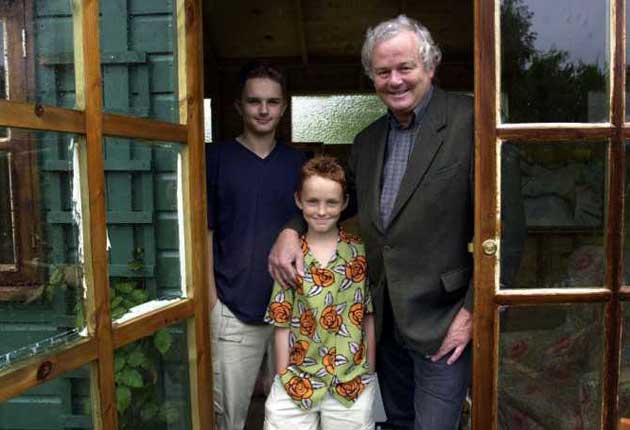

My attempts at fatherhood have just been made into a film. The three of us went to see it recently at a private screening. It was absolutely shattering. I'm not sure if any of us want to go through that again. The film is terrific with handsome, cool, clever Clive Owen taking the lead and two young actors creating a very lifelike impression of the two boys. Seeing yourselves up there, seeing your secret life turned inside out, seeing yourself starring in your own tragedy ... a lot of it looked out of focus, and none of us saw it all.

But there we were. The three of us. A father and two boys, an all-male household. We have been marinaded in our own essence, like nouvelle cuisine.

We went through the boys' formative years with a male view of the world, of family, of daily life. It looked like that National Lampoon cartoon entitled The World Without Women. That showed pandemonium in the neighbourhood with boys on the roofs, battle formations in the streets and footballs being thrown from one house to another.

That was us. That's what we did. It's all there on the screen. Except the swing has been replaced by a zip-wire. They may not have been able to get insurance for the swing.

Our swing, as we're on the subject, was attached to the upper trunk of a 30ft tree on a bank above the house. I'd had to get professionals in with spiked boots to climb up there. When a boy gripped the crossbar at the end of the rope and launched himself he'd swing in a fantastic arc to the level of the first floor balcony. What a rush – it was like a fairground ride.

I never dared go on it myself. If it thrilled children it terrified their mothers, and that, I fear, was part of the thrill of the swing. There was a certain political point to some of our ways. It was important to show that we could do it our way.

At night we played "Come here, little boy". Why should the little boys come to me? In the dark? In the garden? In the shrubbery? Oh, because I loved little boys. Little girls? I loved them too, I wanted to stroke their little faces and give them lovely presents and HARRRGGHHH I GOT ONE! I GOT A CHILD NOW I'M GOING EAT IT! HARRGGHH HA HAHAHA!

That's in the film. We did well keeping out of the way of social services.

That was the best of it, the fun part, out of which I come pretty well in the film. But there's more, of course.

***

My dear old mother died a fortnight ago, God rest her. Looking back, my efforts with my boys were a resistance to the way she'd brought me up.

It's the endless dialectic. One generation goes one way, the next one goes the other.

The young lives of my sister and myself had been surrounded by the horrors and dangers that every young mother fears. Typhoid. Malaria. Rabies. Tetanus. We were two children in India and she managed to get us both back to England alive – that wasn't an obvious conclusion in those days.

Dr "Happy" Thomas approved of the house she and Dad had rented: "Good wide staircase," he said. "Easy to get the coffin out."

Her sense of health, hygiene and decorum came from that time and place.

But as times had changed it was my plan to deny houseroom to these anxieties. Dirt is a form of daily inoculation, I reasoned; just because it doesn't hurt doesn't mean it doesn't work. Wounds should be left to bleed, that was the best way of cleaning them.

Sofas? The point of sofas was to dismantle them and rebuild them as forts. Trees grew mainly to be climbed. Big sea was there for the fighting. The purpose of quad bikes was to drive round the lawn dragging a boy on a tea tray. You kept an eye on children, of course you did, especially round water – especially when swimming in the surf at night you had to keep your eyes open, and indeed make sure the tide was coming in rather than going out ... I know, I know.

But I did get them out alive. Bruises heal and bones mend. The best way of learning caution was to test your thresholds and your limits. It wasn't a theory so much as an instinct, or an operating practice that stemmed from the fact that fathers don't care for their sons in the same way that mothers do. It's not that we care less but that we ... actually, it is that we care less, and that's the truth of it.

Who can care more than mothers? The child in the womb has an actual, physical, flesh-and-blood connection to her body. It is part of her. Not in a romantic, or metaphysical or ideological way. She shares blood supply with the creature. She feeds it. When she suckles it, she passes life from herself to this other part of herself now operating remotely.

She knows the vulnerability of the child because it has been – and in some sense still is – part of her physical being. Of course when the little thing falls over in the playground a mother may clutch at her own knee.

On the other hand, we have on video my younger son aged 14 repeatedly jumping out of a first floor window on to a pile of cardboard packing material and an old mattress on the round. I can watch it without missing a heartbeat. I still wonder whether we took it too far.

I also wonder what else he's got in his autobiography (My Life So Far) – the things I wasn't told about.

***

We live largely in a mother's world these days. Childcare has gone a long way in the other direction; it's public policy now. Health and safety. Coursework. The official way of doing things. The fact that so much we do – even as adults – now has to be pre-approved. Those policemen who wouldn't go into the water to search for a drowning boy? That behaviour wasn't "on the list". That's how it is these days.

They've leached the untidy spontaneity out of public life. For good or ill, our family life did it the other way. My boys were given space to grow up according to their natures. Provided they followed the few, large rules I had in place, they grew up without the pruning and training that mothers like to do. Somewhat carelessly, I now see.

The phrase I taught them to laugh at was: "You'll put someone's eye out like that!" That summed up the automatic anxiety I thought we should resist. Nobody's eye was ever put out, I told them. There were 60 million years of evolution to grow bones round the eyes to protect them.

It was an irony that I nearly did put Alexander's eye out one night. We were playing some catching game in the park one night. I swung my paw quickly behind me and caught him right in the white with a ragged fingernail, tearing his cornea. He still has the scar, a black/red bloodspot beside his pupil. But he still does have his eye.

But of course they miss the pruning and training. That's the way of these things. Whatever you do, the things you could have done become the things you should have done.

In truth, I wish I'd done more of the other way. Because none of these reflections mean I recommend this way of bringing up baby.

Yes, there is freedom, there is laughter and mad shouting around the house. There is cricket in the hall and pizza in the fridge. There is a body board at the top of stairs and a cubic yard of videotapes in the sitting room ...

It is hog heaven, but it has more deficiencies than you might think.

Boys – and girls too I'm sure, though I know nothing about girls – need more than that. One side of life is not enough.

And these liberal instincts are a little chilly. They let you get on with it, but what about the need children have for careful instruction, for careful organisation ... for care?

A mother has that armoury of individual caresses that children need. Mothers have a way of talking that searches out their secrets, finds out their anxieties and soothes them. She has order, she has structure, she has clean clothes and a welcoming kitchen. She has ... a home with an airing cupboard, and her children are brushed and scrubbed before they go to school. She has access to their insecurities, to their hopes, their affections. She has attention.

I know both the boys miss that, in their separate ways. And why wouldn't they? I only have my mother's justification, in the end. I got them out of childhood alive.

***

The book was written a decade ago, and since then we've seen a bit of a wave building in its direction. Advanced opinion now is suggesting that boys and girls have certain fundamental gender differences and need different treatment. The progressive consensus is starting to gather round the idea that the systems of education and child-rearing have been feminised, and that boys need some gender-specific consideration. A bit more running around and shouting, as modern educationalists say.

Here's one of those generalisations. In any enterprise, men generally underestimate the risk and women generally overestimate them. That sounds generally true to me, but even if it isn't we don't estimate risk equally. And when it comes to bringing up children, you need both. Caution and valour, both.

If you want to build a public policy about children, education, character-building, values-implanting ... you wouldn't want to let over-estimation of risk run unchallenged.

It certainly takes a big bite out of male education when you take away valour or violence or competitive sports. A lot of us like competition, and indeed certain forms of violence. A lot of males like hitting each other; and quite a lot don't object to being hit back, if that's what the rules say. We like risk. We enjoy flirting with failure.

In Alex's last year at his kids' school, the whole top year lined up for the 1,500 metres. At the gun, half a dozen boys flew down the track: they were real competitors. The next tranche ran along after them, shortly to fall into a dogged jog. But the bulk of the year wandered along in a walk, drinking from their water bottles in case they dehydrated. They chatted. Alex came sixth, but he'd run an extra lap because no one was counting. If running was what you were good at, there was precious little kudos in it.

The world has been angled away from the things that boys like doing, or seem to be good at. And the rewards are increasingly held in front of the things girls are good at. Such is life – we have yet to expiate our gender crimes. There are 30,000 years of male oppression to work through: it'll be a while yet before we come through the other end.

A report was published in The Independent recently comparing the performance of boys and girls when they first get to school. The girls scored top of everything and the boys didn't score anything at all. And the question seemed to me to be – what exactly were these people measuring?

When Alexander was 11-years-old I asked what the difference was between the boys and girls in his school. He said: "When we get set a question, the girls just answer it. We try to make something of it." They'd twist it and produce something unexpected, and unwanted, just for the exercise of ingenuity, for the pleasure of surprise. It still brings small tears to my eyes. No wonder they didn't get any marks.

***

Do I have a policy on child-rearing? A manifesto for action? Not me, I'm too canny for that.

Two parents are better than one. That seems clear now in a way it wasn't when I married the first time (of two), and divorced, "for the sake of the children". My parents' generation stayed together for the children – my lot divorced for the same reason.

Yes, it's the single most obvious fact about child-rearing. Ideally, children will have two biological parents in the same house, looking after them. That's how the children learn how to live, by looking up to their parents.

Thus, the best thing a woman can do for her children is to love her husband. And the best thing a father can do is to love his wife. It's not something you can legislate for, even now.

It's generally thought better to remove children from the influence of bad relationships than to leave them in situ.

Maybe it's right, maybe not, I go both ways on it. That's why I don't have a policy.

But I suspect children will put up with a lot in order to see their parents under the same roof. Each child is an amalgam of both parents; the separation can be a major psychological attack on a child's mind.

Boys need fathers in the house for many reasons. They need to see how men behave with women. They need to see what to do, how to cope, how to tell the truth, how to make sacrifices, how to collaborate. Fathers are needed for their ancestral role – to protect the mother from the son.

And sometimes the other way round. When the genetic father is in the house there is an evolutionary imperative to keep his hands off the children. But when there is no such genetic link, an obvious temptation comes into play. When you have mum's boyfriend in the house and a 13-year-old girl coming into her sexuality then certain forces come into play that don't exist – or rarely exist – between a biological father and his daughter.

But of course two parents are an ideal. One gives space, the other does the close work. One can yell, the other can comfort. One creates the row, the other soothes it over. One stands back as a quiet authoritative presence, like a designer, the other gets into the thick of it and does the engineering work. Those roles can change, incidentally, and in a moment. But one does this, the other does that: you can only take multitasking so far. We do have two strands of DNA after all, coiling round each other. Separate but dependent on each other. And wonderfully productive, as the best relationships are.

That's the way it's meant to be – and if it doesn't work out like that, we do what we can.

"The Boys Are Back" is in cinemas in January 2010

Woodstock Literary Festival

2009 Simon Carr will be talking about his life as a movie at The Independent Woodstock Literary Festival. He will be interviewed by the journalist Jim White at a special Breakfast at Blenheim event, which will take place in the splendid surroundings of the Orangery at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire, at 9.45am on Sunday 20 September. Tickets cost £12 and include a light breakfast. For details, go to www.woodstockliteraryfestival.com or call 01865 305 305

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments