America's most overweight cities: How Oklahoma is battling obesity

Obesity is a scourge of the Western world, with governments scrambling to defuse a health timebomb. Could a civic revolution in the US Midwest point the way forward?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Velveth Monterosso arrived in the United States from her home town in Guatemala in 2005, she weighed exactly 10 stone. But after a decade of living in Oklahoma, she was more than five stone heavier and fighting diabetes at the age of 34. This friendly woman, a mother of two children, is a living embodiment of the obesity culture cursing the world's wealthiest country.

"In Guatemala it is rare to see people who are very overweight but it could not be more different here," she told me when we met in Oklahoma City a few weeks ago.

In Guatemala, Mrs Monterosso ate lots of vegetables because meat was expensive. But working from eight in the morning until 11 at night as a cook in an Oklahoma City diner, she skipped breakfast and lunch while snacking all day on burger and pizza.

Driving home after 15-hour shifts slaving over a hot grill, she would often resort to fast food because she was still hungry. If she and her husband Diego – also a cook – made it back home without stopping, they often gorged on whatever was available rather than wait to cook a decent meal. Her lifestyle was no healthier when she stopped working after having her second child earlier this year. She was tired and her family encouraged her to drink lots of atole – a heavily-sweetened, corn-based drink popular in central America – to aid the breastfeeding of her daughter, Susie. Sugar levels in her body soared on top of her obesity and she became pre-diabetic.

Velveth's life was changed – and probably ultimately saved – when she took Susie for a medical check-up and was enrolled on a programme to curb obesity. Now she eats fast food just once a week, cooks more vegetables, cuts down the number of tortillas consumed at meals, and exercises daily by walking up and down stairs for 20 minutes. Although still overweight, she has lost 16 of those pounds gained in America in just four months. "All my friends are impressed," she told me with a smile. "I feel like I have so much more energy now. I can do the shopping and laundry, bathe the baby, and I'm not nearly so tired as before."

Velveth is just one beneficiary of a remarkable attempt to tackle obesity. For Oklahoma City has declared war on fat – and while the US's obesity problems are worse than the UK's, this fight has lessons for the wider world. It started when the mayor, realising that he himself had become clinically obese just as his home town was identified by a magazine as one of America's most overweight cities, challenged his citizens to collectively lose a million pounds. This veteran Republican politician then took on the car culture that shaped his nation, asking for a tax rise to fund a redesign of the state capital around people.

This unleashed a remarkable range of initiatives, including the creation of parks, sidewalks, bike lanes and landscaped walking trails across the city. Every school is getting a gym. With the new emphasis on exercise, Oklahoma City spent $100m creating the world's finest rowing and kayaking centre – this in a Midwest town with no tradition of the sport beforehand. Resources poured in to challenge overweight people's lifestyles, backed by hard data on health.

The experiment is unusual in terms of its ambition, breadth and cost, all of which take it beyond anything being attempted by other American cities. The battle is being done with the co-operation, rather than the resistance, of the fast food industry and soft-drinks manufacturers. It relies largely on persuasion instead of coercion. Jamie Oliver might be interested to know there are no soda bans or sugar taxes. Oklahoma City has been dubbed "a laboratory for healthy living", yet perhaps the most extraordinary thing about it is where it is happening.

Oklahoma City is one of the US's most spread-out urban environments, covering 620 square miles, which means the 600,000 residents rely on cars and there are so many freeways that they quip "you can get a speeding ticket at rush hour". Not only did it not have a single bike lane, but it also reputedly had the highest density of fast food outlets in America, with 40 McDonald's restaurants alone. It sits in a state seen as cowboy country, symbolised by John Steinbeck's novel The Grapes of Wrath about poor farmers driven away by drought and hardship in the 1930s. The economy collapsed again in the 1980s amid the energy crisis, with bank closures and another generation drifting away. Then came the 1995 bombing that killed 168 people.

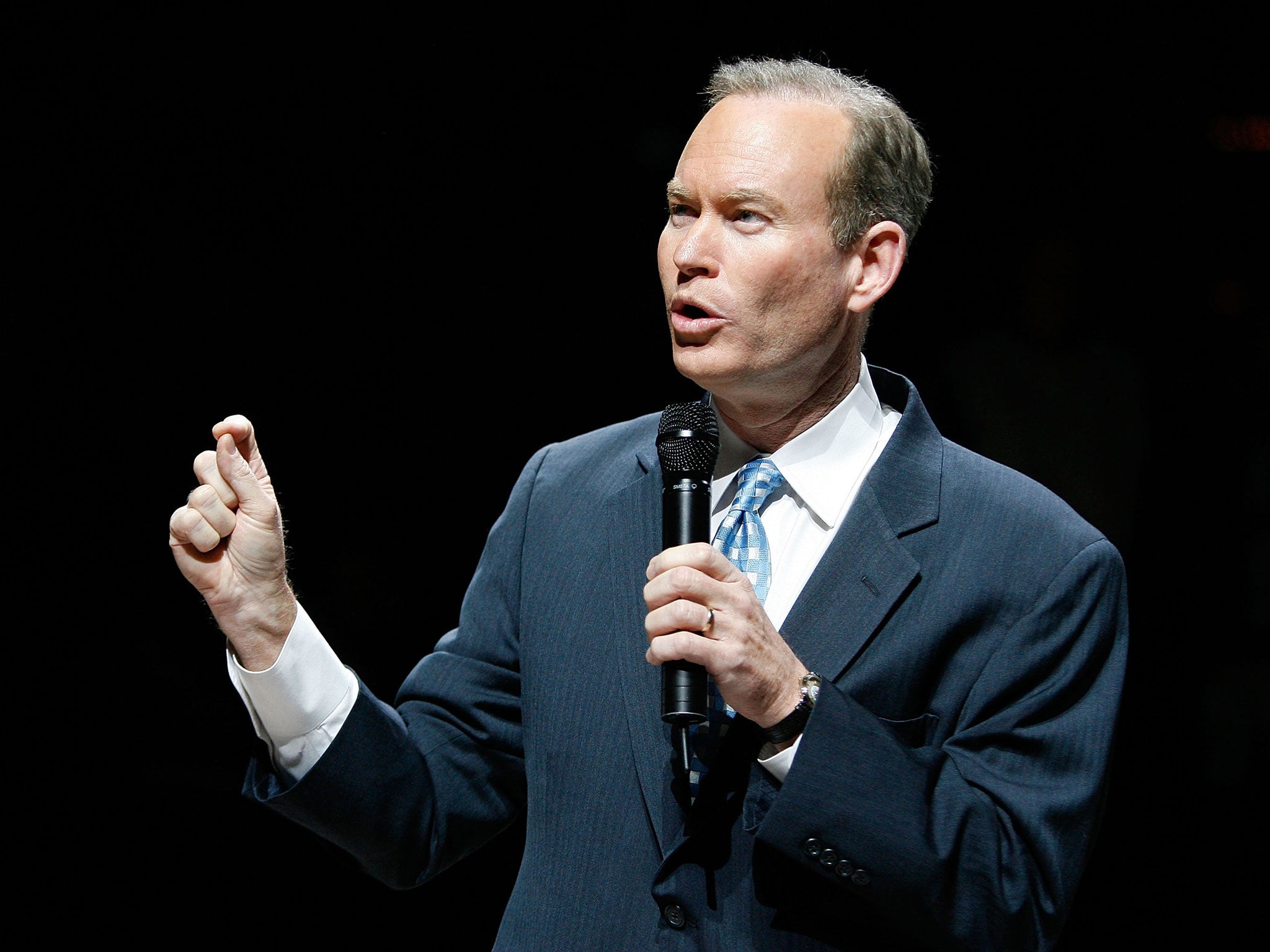

The mayor behind the transformation is Mick Cornett, a former television sportscaster who took office in 2004. Three years later he was flicking through a fitness magazine when he noticed his city had been given the unwanted accolade of having the worst eating habits in the US and was prominent on a list of the nation's most obese populations.

"This list of obesity affected me as mayor, and when I then got on the scales it affected me personally. I have always exercised and I remember thinking that I did not eat between meals, yet I was eating 3,000 calories a day. As mayor people are always wanting to meet with you, so it was not unusual to have a business breakfast then a lunch with someone, then a function dinner. And in between there can be events with snacks and cookies."

Cornett persuaded a healthcare magnate to fund an information website called This City Is Going On A Diet. Local papers backed his campaign. Churches began setting up running clubs; schools discussed diet; companies held contests to lose weight; chefs in restaurants competed to offer healthy meals. And people across the city began acknowledging that there was a crisis.

Almost one third of adult Oklahomans are obese, while the state ranks among the worst in fruit consumption and for life expectancy in America. Diabetes rates had nearly doubled in a decade. Perhaps most alarmingly, more than one in five children aged 10 to 17 suffers obesity, and almost one third of pre-school infants are overweight.

Cornett decided from the outset to work with the food and drink industry. So the soft drinks sector sponsored health programmes to fight obesity and the mayor posed with the boss of Taco Bell in one of the chain's outlets to publicise a low-fat menu. He keeps one of the company's promotional cut-outs in his office and proudly showed it to me when we met. "Even when I lost weight I would go to a fast food place, although I might have a bean burrito without sour cream," Cornett told me. "I could not stop people going to them but I could try to make them more discerning with > their orders. You can't totally change people's habits."

In January 2012, the city hit the mayor's million-pound target – 47,000 people had signed up, losing on average more than 20 pounds apiece. An admirable achievement, with the campaign proving a clever way to raise awareness. But for all the publicity, Cornett's ambitions had grown way beyond that original simple stunt: now he wanted to remake his huge metropolis by remoulding it around people in place of cars.

He contacted a planning expert named Jeff Speck, who conducted a survey into the city that concluded that it had twice as many car lanes as it needed. The result was the dismantling of its one-way system, seen as encouraging faster driving, along with the start of a project to install hundreds of miles of pavements, parks, trees, bike lanes, sports facilities and on-street parking to create a "steel barrier" between those thundering freeways and pedestrians.

The scale is impressive. The city's downtown is being rebuilt, while next up is the creation of a 78-acre central park, since studies show people exercise more if close to green spaces. "The American healthcare crisis is an urban design problem," argues Speck, author of a book called Walkable City.

"The lack of attention to such issues has been a huge black hole. Data shows that physical health and obesity are tied much more to physical exercise than to diet. But what makes Oklahoma unique is its willingness to invest so generously, for which it must be commended." Cornett estimates that about $3bn has come from public funds, with up to five times that sum spent by the private sector. There was, for example, just one struggling hotel downtown at the turn of the century; today there are 15 and I found it difficult to book a room at short notice. Remarkably, residents voted to pay for this redevelopment with a one cent rise on the local sales tax, which raised about $100m a year.

Other funds were taken from tobacco settlements and rising income from property taxes as firms and people were attracted back. Oklahoma City currently has among the lowest unemployment levels in the country.

The most unexpected part of the makeover can be found a few minutes' walk from the city's entertainment district of Bricktown. One of the world's finest rowing facilities has been created in a town with no tradition of the sport. This is a city that even the mayor's chief of staff says was a "horrible" place when growing up. Yet what was once a dried-up river in a ditch best avoided by decent folks at night, is now a sparkling three-mile stretch of river, fringed with lush landscaping, futuristic-looking boathouses, bike lanes and floodlights.

According to Shaun Caven, a Scotsman who led the gold-medal winning British canoe and kayak team at the 2008 Olympics in Beijing before moving to be head coach at Oklahoma, this will be the best set-up in the world with the completion of its $45m white-water course. There are even altitude training facilities in one of the hi-tech boathouses. "People thought I was mad when I moved here," said Caven, who is 47. "They said, there's no water. The impression is of a bone- dry landscape. But I liked the fact there was no history and the chance to start something from nothing."

The river feels a long way from rowing's upper-crust heritage. People on paddleboards and school parties on dragon boats share the water with US Olympic teams in training. Efforts are made to attract people from across society; 50 firms have joined a corporate league, while eight local high schools have their own boats. Among those I met there was Bob Checorski, a 76-year-old sweating from his exertions after rowing an impressive 11,000 metres, who told me he began six years ago after losing free gym membership at work. "I do it for relaxation rather than racing, although I did win a silver medal in a doubles race soon after joining with a guy who'd had open-heart surgery," he said. "Now I just go out and enjoy myself."

.jpg)

But plush sports facilities, nice parks and pleasant sidewalks can only go so far in fighting a culture of rampant obesity. Many people need more encouragement. So six years ago the city started poring over all available data to find its least healthy zip codes, discovering that some disadvantaged parts have more than five times the death rates from strokes and cardiovascular conditions compared with wealthier areas. This led to the redirection of funds into places most in need.

"Obesity is the underlying cause of almost every chronic condition we have in Oklahoma," said Alicia Meadows, director of planning and development at Oklahoma City County Health Department. "If you direct significant resources into the areas of greatest health inequalities, we think you make the biggest difference."

The department has an eight-strong team of outreach staff going to markets and sports events. They even call door-to-door in areas that data indicates are home to people in need of most help. "We make it clear that we don't want to see their papers; we know many are undocumented. But their health impacts on the city's health."

These outreach officials come from the same communities they seek to change. One is a mother-of-two from an impoverished Mexican background, who told me she used to know nothing about nutrition. Now she has lost five stone and taken up kick-boxing. I watched Dontae Sewell, another convert, lead a Total Wellness class in a library, making self-deprecating jokes about scoffing burgers at barbeques as he explained the etiquette of healthy eating. "If your friends love you, they still gonna visit even if you just serve them vegetables," he declared.

The lesson was good-natured, with lots of banter and little homilies alongside advice on when, what and where to eat. The class of 22 women and one man, mostly overweight and some clearly obese, had lost 200 pounds between them in five weeks. "We want to see our grandkids," one middle-aged mother told me afterwards. Sewell, with chunky silver cross around his neck, asked how many ate at the table; just four raised their hands. Then he asked how many fast food outlets they passed on their way home from work. "Two dozen," replied one woman. "Too many," said another, laughing. "Don't be too hard on yourselves," said Sewell. "It's about small changes and creating new habits." Afterwards he confessed only about one third stuck to their lifestyle changes.

The city has built specialist "Wellness Campuses" in its worst-affected areas, the first in a low-income, largely African-American area to the north east of the city. The slick new building – filled with medical clinics, communal meeting rooms and kitchens for cooking demonstrations – sits in verdant grounds dotted with walking and bike trails. Patients at the private-public partnership can see specialists in everything from nutrition to domestic violence, taking home prescriptions for food boxes and soon even for running shoes and vests. The local soccer team is building its training ground beside the campus to encourage participation in sport.

Battle of the bulge: How America's weight problem has piled up over the past five decades

35% of US adults are now diagnosed as obese

20% of US children are diagnosed as obese

11st 9lb Average weight of US male in the 1960s

14st Average weight of US male in 2015

10st Average weight of US female in the 1960s

11st 9lbAverage weight of US female in 2015

3,770 Average daily calorie intake in the US today

2,500 Recommended daily calorie intake for men

2,000 Recommended daily calorie intake for women

$147bn Estimated annual medical cost of obesity in the US (2008)

$1,429 Extra medical costs per year for obese people in US over those of normal weight

There is no doubt Oklahoma City and its fat-fighting mayor deserve credit for their war against obesity, an inspiration for a country in which two-thirds of the population is overweight and has such a strong car culture. At the very least, they have made their hometown a more pleasant place to live. Yet the key question is whether even such valiant and wide-ranging efforts can put a dent in such a huge health problem. One Lancet study from last year looking into three decades of global obesity found not one of the 188 nations studied had managed to turn the tide on a crisis that worsens by the day.

There are signs of success, although mayor Cornett is not making big claims. "All I will say is that my impression is we are going in the right direction," he said. He is sceptical about data on obesity, but health indicators seem to back him. In the lowest-income areas of Oklahoma City, where there are the highest rates of diabetes and blood-pressure problems, they have cut key indicators by between two and 10 per cent in five years. And while Oklahoma men live almost six years less than the national average, the city has seen a three per cent fall in mortality rates.

Yet while the rise in obesity has slowed down – from six per cent a year to one per cent – it is still increasing. No wonder many experts compare this struggle to the anti-smoking movement. That took decades of campaigning, education and regulation to change societal behaviour.

This was underlined to me the night before leaving Oklahoma City as I ate in a restaurant recommended by Cornett's office. After a superb plate of pasta, I was offered desert and chose a "roasted pecan ice cream ball... smothered in chocolate sauce". The waiter said that was a good choice, then asked if I wanted it "volleyball, softball or baseball sized?" I went for the smallest (baseball). It was delicious and absurdly filling. But a posh restaurant offering volleyball-sized portions of ice-cream? As Cornett says, it is hard to change habits in the battle against obesity.

This is an edited version of a report first published by Mosaic (mosaicscience.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments