The age of inactivity: How laziness is killing us

Even Before Christ, Hippocrates saw exercise as an elixir of life. So why has inactivity become so appealing, and at what point did we forget that exercise makes us feel good?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Two thousand years ago, Hippocrates, the Father of Modern Medicine hit the nail on the head. He said, that if we all had “the right amount of nourishment and exercise, not too little and not too much, we would have found the safest way to health”. Bingo.

Obviously then, being a species of great intellect, over the next two millennia we took on his sensible advice, integrating exercise into our daily life and cashing in on the rewards for our bodies and minds. Hmm, maybe we didn’t quite all get that memo. Instead something else happened and physical inactivity grew into the fourth largest global killer in the world (according to the World Health Organisation), with some claiming it takes more lives than smoking, diabetes and obesity combined.

Yes, physical inactivity has its price tags. It is linked to the development of chronic health problems like heart disease, type 2 diabetes, obesity, depression, dementia and cancer. It can make us feel bad about ourselves, guilty and frustrated, appeased only with the ever alluring reward of inactivity – comfort, rest and stress-free. Our creaking NHS too gets a bill that would make anyone wince reaching for their wallet – somewhere between £8 and £20 billion per year through both the direct and indirect healthcare costs including that on the economy. Ouch.

The third price tag, and possibly most in need of an active not passive reaction, is the generational one. There is growing over the degree of inactivity in children with precipitants embedded within our shift to a more sedentary lifestyle, fear and risk associated with outdoor play, and the advent of more advanced and ‘real-life replacement’ for one in four children who see online social networking and gaming as their activity. Even more sobering is the evidence that suggests many children still have a negative approach to physical activity in schools, with teachers believing that nearly half of primary school pupils leaving school without “basic movement skills”, and that more than one in three children dislike exercise by the time they leave primary school. These barriers can potentially frame their adult sedentary life. A high price tag indeed.

Make no mistake, these are massive, insidious, chronic alarm bells. So it’s no surprise that in an effort to stem the physical inactivity shock-wave, there is an increasingly louder call from healthcare, academic and government sectors to seed physical activity firmly at the heart of our healthcare system.

You know it makes me wonder if Hippocrates and those after him could ever have foreseen such a crisis point. Then again that’s not what worries me as a doctor. What worries me is why so many of us are still not getting its importance to our lives? Or then again, is it simply a change in our psychology to life, to our society, and to our drive to fix this crevassing “knowing-doing” gap?

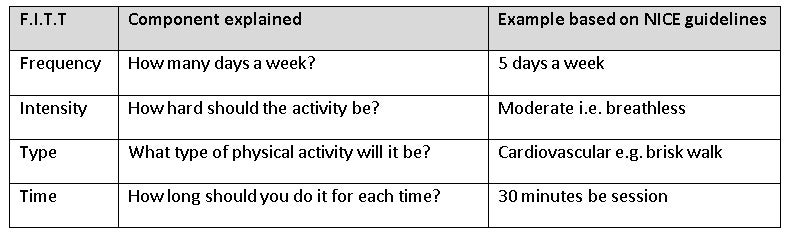

Right then, here’s a question - how big do you think this gap is? I agree, it is a vague question. However one way to answer it is to consider what the national physical activity guidelines, as set out by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), actually expect us to do each week. I warn you, for some of us (including me on some weeks) this may prove an entertaining read. So if you’re between 19 to 65 years, all raise your hands if, each week, you are moderately active (e.g. a brisk walk) for 30 minutes a day for 5 days and complete 2 muscle strengthening sessions? I reckon there are still some hands resting neatly on laps or pockets. Well, in fact, in the UK, 60-70% of us take insufficient exercise. You can’t run away from that fact. (And you might not fancy running, anyway).

Like a dodgy set of scales, this gap has grown so big because of a huge imbalance; imbalance between factors promoting physical activity and barriers to it. I’m actually going to skirt over promotion factors because for me, the only one that truly acts (and works) as your own activity ‘engine’ is your own self-motivation. The juicier issues are the barriers. Many barriers are ironically often a direct response to progression in other parts of our lives.

Think about it, we have relationships and families that generate temporal and financial responsibilities, and we work longer and harder than ever so generating energy, temporal and focus demands. This is all too in the context of a higher cost of living – including those pound-draining gym memberships and a society that has shifted its preference to that of sedation and calorie excess. All the above, without fail, contribute to the fact that nearly 25% of the adult population are now classed as obese, and nearly 60% of the remaining are classed as overweight. It’s almost as though our health is an indirect victim of our and our society’s success.

With all these bloody barriers to hurdle there’d better be a good reason to do some physical activity. Hippocrates, saw exercise as an elixir of life, even without knowing what we do now. But he was spot on. Regular physical activity can benefit you medically (extend your life by around 4 years, and reduce your risk of heart disease, cancers and weakened bones); cognitively (increase brain chemicals which promote better memory and learning); psychologically (yes, it is true that those endorphins can lift mood and de-stress!); and physically (by controlling weight and offsetting calorie-dense diets, and giving you more energy with better metabolism, muscle strength and endurance). You know this though don’t you. It’s obvious and we’ve all had a taste of its benefit – even if it was just for those first two weeks in January when in ‘resolution’ mode.

Let’s be realistic, when it comes to physical activity, despite guidance by NICE, a one size approach doesn’t fit all. And I’m glad about this because the spectrum of what physical activity consists of, why you’re doing it, and how you want to do it should be limitless and bespoke. Besides the classical gyms, physical activity can be manufactured all around you – from your daily activities (like taking the stairs not the lift), to commuting (where you walk to the station rather than go on the bus), to using the outdoor spaces (like the parks) – not to mention the positive abundance of new diverse and fun boot-camps, group-park runs and local exercise groups emerging. Your creativity is your only limitation.

Now you might be a seasoned exercise guru, Mr or Mrs Motivator, twice a week frequent-flyer at the gym or a couch potato. If you’re not in the latter category then brilliant – keep going and encourage those around you. If however you are the latter and looking to take that first step to exercise, which, can feel as daunting as that first day back at work after a two week holiday, then listen up. Making that first step may be the hardest but it will be the most rewarding step you make.

Before you take it you need a plan. Now I like simple, so my plan has only two steps; Step 1 – write down your motivation, asking yourself the following about your goals: what is it, why do you want it, when do you want to achieve it, what can help it and what may hinder it. Always remember to do this in the realistic context of your own busy life and please, never be hard on yourself - you are taking action! Step 2 is to apply your goals to the “F.I.T.T principle”, a way to plan your exercise. I’ve summarised this below:

Now I very much doubt you’ve come to the end of this article with an epiphany on physical activity. What we have discussed is a drop in the ocean of the issues around physical activity, a growing, confusing and quickly-evolving subject. After-all, it’s tightly woven into the fabric of our society and intertwined with nutrition, motivation, opportunity and need. So this article merely hopes to act as a trigger to kick-start those of you who do no exercise, and positively reinforce those of you that exercise already.

An awareness of the pitfalls of physical inactivity are important to know, yes, but the overwhelmingly positive effects that physical activity has on our lives is a far, far superior means to encourage us towards exercise. I think of it as this - the former mimics an uncomfortable spiky ‘prod’ from a stick dangling with negativity whereas the latter acts as the proverbial carrot dangling in front of us with the prospects of better health, energy, and mood. The catch, I have realised, is that you have to be the one dangling your own carrot. It is only your own tailor-made and personally-inspired carrot that will ultimately narrow that knowing-going gap. I know that my carrot is certainly still a work in progress…

Dr Nick Knight is a junior doctor based in London with a PhD background in human performance www.drnickknight.com

@Dr_NickKnight

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments