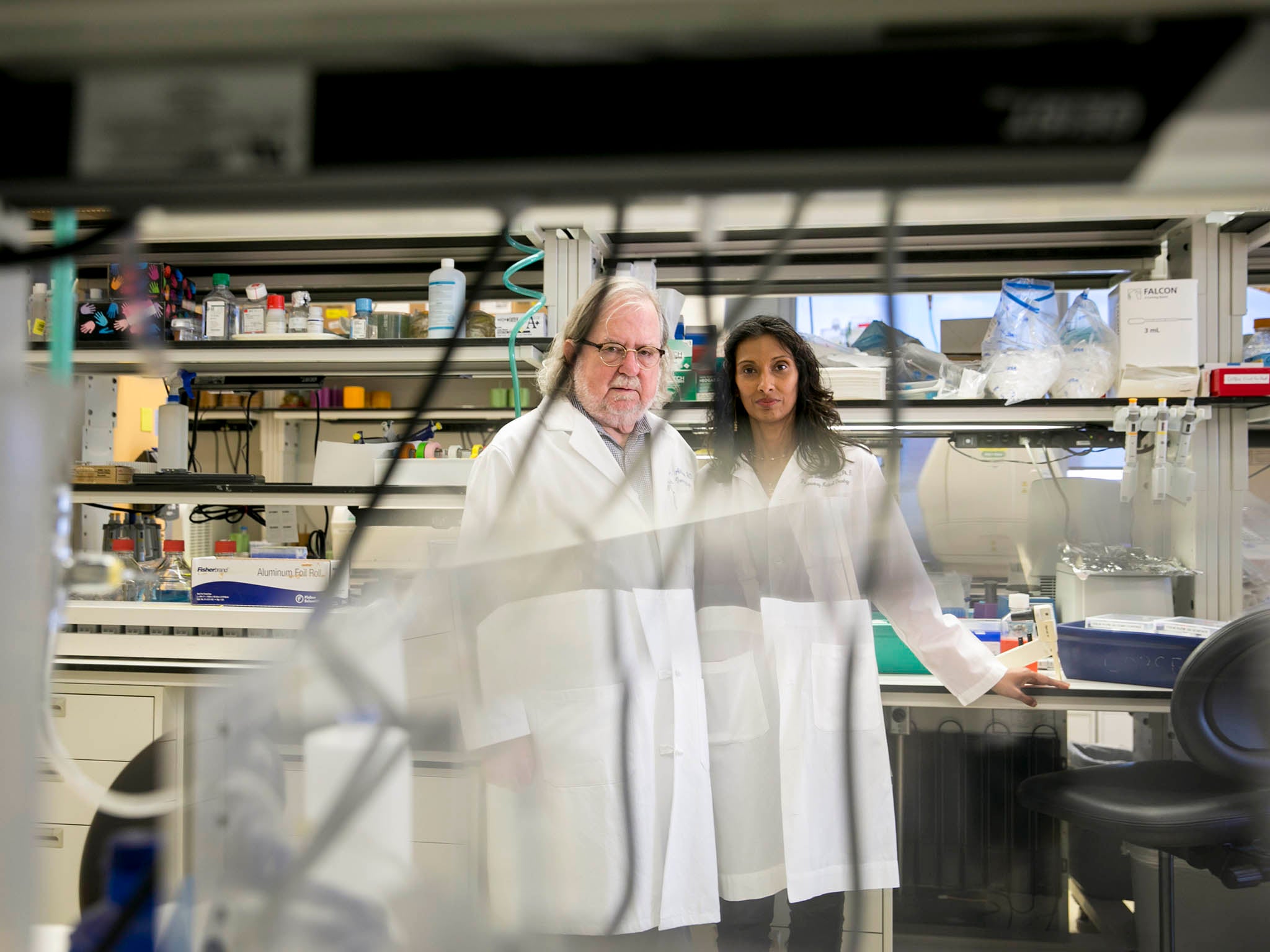

Cancer-fighting power couple tackles mysteries of the immune system

Jim Allison and Padmanee Sharma, cancer-fighting power couple and famous research collaborators, are trying to push the frontier of immunotherapy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Cancer researcher Jim Allison stands at the edge of a small stage, fiddling with his harmonica, his unruly grey hair hanging almost to his shoulders. Soon, surrounded by eight other cancer experts who also happen to be musicians, he’ll be growling out the classic “Big Boss Man” before a boisterous crowd at the House of Blues.

It’s a fitting number, says Patrick Hwu, who plays keyboards for the band and is Allison’s colleague at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Centre in Houston. “When it comes to immunotherapy, he is the big boss man.”

Few would disagree. In recent years, Allison’s work has ignited a revolution in oncology treatment that frees the immune system to attack malignant tumours. Patients near death have returned to live full lives. The drug class he pioneered, called checkpoint inhibitors, now includes a half-dozen therapies that have spawned a billion-dollar market. So stuffed is his office with scientific awards that some sit in boxes on the floor. He is frequently in contention for the Nobel Prize in Medicine (which this year has been awarded to Jeffrey C Hall, Michael Rosbash and Michael W Young for their work how molecular mechanisms control circadian rhythms).

But amid the successes, these are challenging times for Allison and the oncologist who is his key partner – and who typically is front and centre in the audience when his band plays at fundraisers like this. Padmanee Sharma is a formidable researcher and immunologist at MD Anderson: a specialist in renal, bladder and prostate cancers. She is also Allison’s wife.

In their particular corner of the universe, they are the ultimate power couple. Yet they, like other immunotherapy enthusiasts, find themselves grappling with the downsides of the new treatments. The therapies can cause serious side effects and, while effective for some patients, are far from foolproof. And they have largely been a bust for cancers of the prostate and pancreas.

Allison and Sharma feel the frustration acutely, saying that many more people must be helped. “We need to get the numbers much, much higher,” he says.

Even as they pursue the next breakthrough, their lives are a frenetic mix of science and celebrity. Allison’s role in developing immunotherapy has won him the adulation of both patients and philanthropists. The couple has flown on philanthropist and former financier Michael Milken’s private jet, been escorted on backstage tours by U2’s The Edge and attended high-wattage Vatican stem-cell conferences.

At the Smith & Wollensky’s where they frequently dine in Houston – where Allison proposed to Sharma, there are wall plaques inscribed with their names near their usual table.

Still, they reserve most of their energy for their science. They say immunotherapy’s problem is that its use in patients has outpaced a fundamental understanding of how it works.

To remedy that, they are running an ambitious program that links animal research, novel human trials and intense monitoring of tumours via repeated biopsies. By analysing the malignancies before, during and after treatment, they hope to better understand the interaction among the cancer, the treatment and the immune system. They know that using combinations of therapies for cancer will probably be the key to better outcomes for patients, but they need to figure out exactly which drugs to use, and how.

Allison doesn’t hesitate to tell Sharma what works best for laboratory research. She pushes back on any suggestions that might not help patients, reminding Allison he isn’t a physician. And if they can’t compromise, who wins?

“Pam,” says the gravelly-voiced Allison. “She’s louder.”

“I just want things to move things faster,” she counters.

***

On the sprawling MD Anderson campus, Sharma speed-walks, doling out medical advice, pep talks and the latest test results.

She warmly greets Michael Lee Lanning, a retired Army lieutenant colonel who was diagnosed with kidney cancer in 2003. Within three years, the disease had spread throughout his body, and doctors sent him home with painkillers and phone numbers for hospices. He was 59.

Looking for a reprieve, he went to MD Anderson and met Sharma. “She looked me in the eye and said: ‘Everyone will die, and some will die sooner,’” he recalled. A “cold bitch,” he told his wife.

But as he ran through treatment after treatment, Lanning came to appreciate Sharma’s refusal to give up. Two years ago, she had him enroll in a trial testing a combination of radiation and Yervoy, a medication developed by Allison that was the first checkpoint inhibitor approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The treatment kept Lanning’s cancer under control until this past December, when the tumours once more began growing and he repeated the one-two punch of radiation and Yervoy. More recently, to keep the tumours in check, he began taking a different immunotherapy drug.

“I didn’t think I’d make it to 60,” said Lanning, who is again stable. Now he’s 71 years old. His beloved granddaughter, who was eight when he was diagnosed, is now in college.

Sharma has pushed for close monitoring of tumours in various stages of treatment for years, believing that it provides critical clues about why only some patients respond to immunotherapy and about how to design subsequent trials and experiments.

Allison, a fan of the strategy, made its broad expansion a condition of his move from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre in New York, to MD Anderson in 2012. Today, about 100 of the centre’s trials involve such intense surveillance.

While other cancer hospitals do similar analysis, the scale of the effort at MD Anderson sets it apart. “I’m jealous,” said Charles Drake, co-director of the cancer immunotherapy programs at Columbia University Medical Centre in New York. “They can apply state-of-the-art analytical tools to tumour specimens before, during and after treatments – and see the results in real time.”

Now Sharma and Allison are bringing their approach to advanced prostate cancer, which is notoriously resistant to immunotherapy. Previous research has shown that combining two immunotherapy drugs might be better than using just one. In a trial overseen by Sharma, one drug is used to drive T-cells (the foot soldiers of the immune system) to the tumour, and a second to block proteins that keep those soldiers from attacking the malignancy.

“We have to try,” she says. “At least these treatments give our patients a chance.”

***

By outward appearance, Allison and Sharma are opposites. She’s 47, striking and model-thin; he’s 69, rumpled and pudgy.

Just as pronounced are their similarities. They bonded years ago over their shared obsession with T-cells, and these days, Sharma says, “we talk about data all the time, at dinner, while brushing our teeth.”

Allison grew up in a small town in South Texas where his country-doctor father made house calls. His mother died of lymphoma when he was 11 – just the first of many family losses to cancer. Two uncles and a brother later died of the disease. Allison has battled early-stage melanoma, bladder and prostate cancers.

He went into cancer research not because of family history, but because he always wanted to be the first person to figure something out. Early on in classes at the University of Texas at Austin, he realised that medical school wasn’t for him. “If you are a doctor, you have to do the right thing; otherwise, you could hurt somebody,” he says. “I like being on the edge and being wrong a lot.”

Allison did not attend medical school, but he did earn a PhD from the University of Texas at Austin. In the mid-1990s, while doing research at the University of California at Berkeley, he became intrigued by a molecule called CTLA-4, which exists on the surface of T-cells. It was widely thought to spur the immune system into action.

Allison and immunologist Jeffrey Bluestone at the University of California at San Francisco independently proved just the opposite: the protein actually slammed on the immune system’s brakes. Allison wondered about the implications for cancer. If this brake – called a checkpoint – were disabled, would T-cells hunt down and destroy tumours?

To find out, his lab developed an antibody that blocked CTLA-4 and injected it into mice with cancer. The tumours melted away. That work led to a 1996 landmark paper describing a radical new anti-cancer approach targeting the immune system, not the malignant cell. It was called “checkpoint blockade”.

“Jim Allison’s conceptual insight opened up the whole field,” said Antoni Ribas, a leading oncologist and immunologist at the University of California at Los Angeles.

Allison was determined to get the compound into human testing. “I wasn’t going to let anyone get in my way,” he says. After years of badgering sceptical pharmaceutical companies, he finally persuaded a company later bought by Bristol-Myers Squibb to test the drug for advanced melanoma – which at the time was almost always lethal.

Sharon Vener, 65, was in one of the first trials. In the mid-1980s, the mother-of-two had a small mole that turned out to be melanoma. 16 years later, the disease returned with a vengeance – as an inoperable, baseball-size tumour attached to her heart, lungs and chest wall; she also had several tumours in her liver.

Her doctors, including Ribas, tried a few treatments. All failed. As a final effort, he enrolled her in a first-in-human trial of Allison’s immunotherapy drug. Her tumours began to shrink after a single dose.

“Every birthday, it’s like, ‘Oh my God, I’m still here’,” “ Vener says. A decade ago, Ribas introduced her to Allison as the man who had saved her life. The two hugged and then cried.

***

Sharma’s father, an engineer in Guyana, ended up as a handyman after he and his family fled political turmoil to the US in 1980. They settled in a tiny basement apartment in “Little Guyana” in Queens, and her mother cleaned houses. Sharma was 10.

A standout student, she would go on to graduate from Boston University and earn a medical degree and PhD in immunology from Pennsylvania State University. After further training at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre in New York, she was hired by MD Anderson in 2004.

She and Allison met at a scientific meeting the following year and began collaborating. For a long time, she was leery about getting personally involved with him. “I didn’t want to worry that everyone would think my ideas were actually his ideas,” she says.

By now she has her own significant achievements, including being the first to show that a T-cell protein called ICOS boosts the effectiveness of some immunotherapy. In Houston, both she and Allison have impressive portfolios.

He is chair of MD Anderson’s immunotherapy department and executive director of what the cancer centre calls its immunotherapy platform: a large effort to understand cancer and the immune system. She is the platform’s scientific director, and between the two of them they preside over three labs and dozens of people. Every week, they and their team review four or five trials to try to discern patterns, decide which animal tests to conduct and how to design new human studies.

In their personal lives, the constant talk of T-cells sometimes perplexes Sharma’s three daughters from a previous marriage. But they are familiar with their mother’s focus. She says she has never felt guilty about the demands of her job; her patients desperately needed her, and her daughters were lucky enough “to grow up healthy in a world with indoor plumbing and Cheerios”.

Plus some perks: these days, Sharma drives a Porsche with a vanity licence plate that says CTLA-4, a reference to her husband’s work. And he drives a Tesla with a plate that says ICOS, a nod to hers.

***

But back to Chicago and the House of Blues restaurant, where band The Checkpoints are well into their set. The show, held annually during the biggest cancer conference of the year, raises money for grants awarded by the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

Allison’s fame and his facility with the harmonica have provided unique opportunities, such as accompanying Willie Nelson and his band at the Redneck Country Club near Houston. Tonight, however, clad in a black Hawaiian shirt, he’s performing for a different crowd.

The big boss man is the picture of cool as he steps up and plays “Take Out Some Insurance on Me, Baby”. Dancing right in front, as always, is Sharma.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments