Father's Day reminder: Men, don't ignore your biological clock

Yes, it exists and it may be more in sync with women's than you know. Lisa Bonas reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Rahsaan Williams was buying his last car four years ago, he asked a lot of questions at the dealership about whether each model he looked at was kid-friendly. How easily could a car seat be installed? Were the seat belts adjustable so they wouldn't choke a child once she was big enough to ride without a car seat?

"I think that they assumed there was a baby on the way," Williams, who works for the federal government, told me recently.

He doesn't have kids, but he does have a goddaughter, Anabel, with whom he spends a lot of time. (Hence all the car seat questions.) He also wants children of his own. At age 38, he thought he'd be a father by now, or at least heading in that direction with a wife or girlfriend. Instead, he finds himself single with a growing sense that time is running out to have a child with someone.

His eagerness to be a dad began as a low hum nearly a decade ago, when Anabel – whose mother is a close childhood friend – was a newborn, curled into a ball and asleep against his chest. It grew stronger about a year ago when he realised he wanted "to be part of taking care of a child. Or part of something bigger than just me."

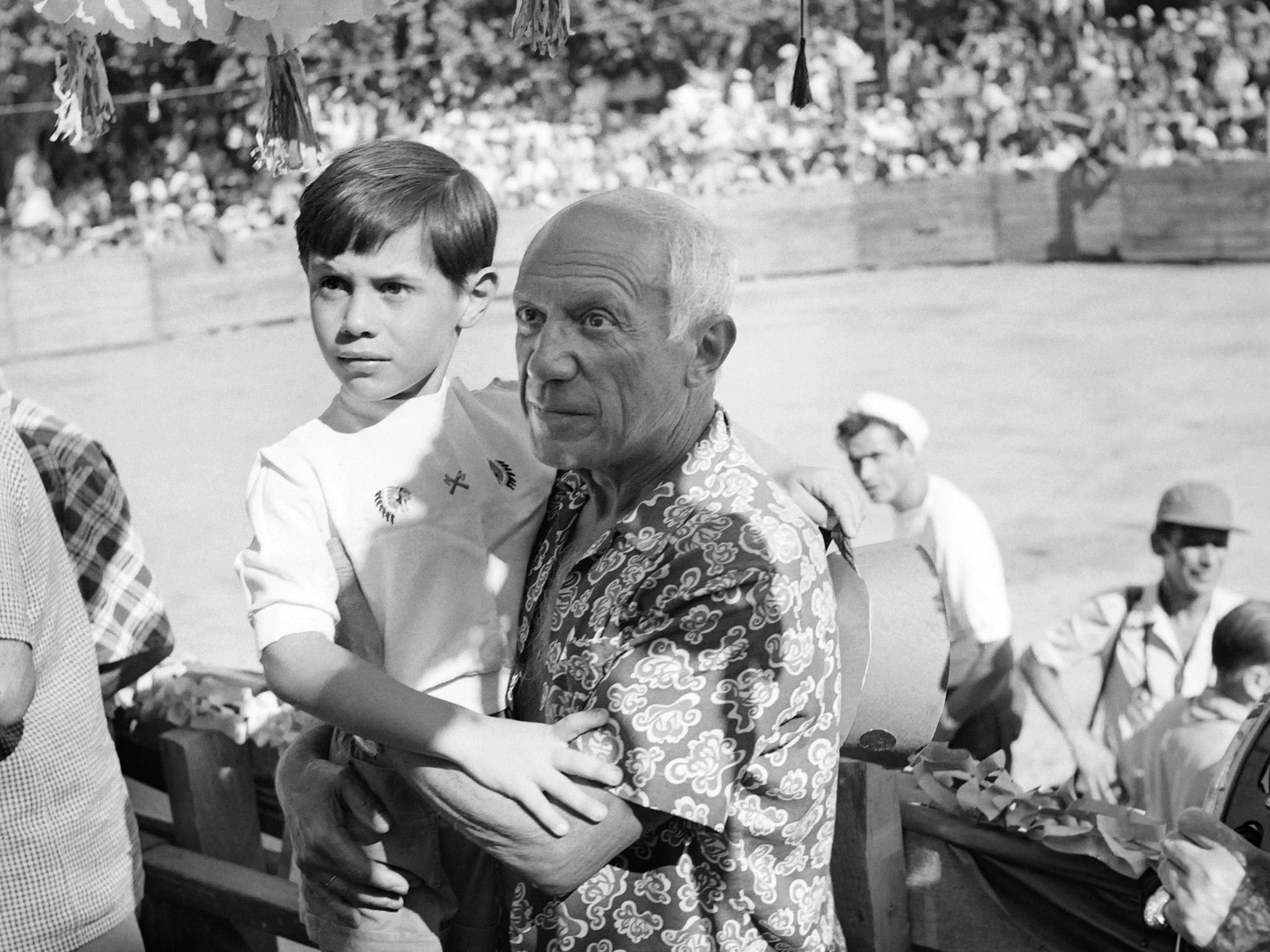

Commentators have long pointed to the famous examples of elderly fatherhood – Charlie Chaplin fathered a child at age 73, Pablo Picasso at 68, Clint Eastwood at 66 – as evidence that men don't have biological clocks. Even the US president is part of the old-dads club: Donald Trump first became a father at age 31, and his fifth child, Barron, was born when Trump was 59.

When the term "biological clock" as it applies to fertility was coined in The Washington Post, it was applied exclusively to women. "This is where liberation ends," Richard Cohen wrote in a 1978 column. "There are some things [men] never had to worry about. Like the ticking of the biological clock." ("It's just a biological fact," Cohen said when I asked him about it last year. "I didn't invent it.")

But nearly 40 years after that column was published, men arguably have more reasons than ever before to pay attention to their own biological clocks. One factor is that couples are getting married later. (Most births still take place within marriage.) In 1960, the median age for a first marriage in the United States was 20 for women and 23 for men; today, it's 27 for women and 29 for men. And for the first time in US history, women in their thirties are now having more babies than younger women, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention reported last month. That shorter window of post-marriage fertility obviously affects their husbands' chances of having kids, too.

This is especially true in a workaholic, focus-on-your-career-in-your-20s place such as Washington, DC, where people marry even later. Plus, there is virtually no marriage age gap in Washington between women and men: according to 2015 US Census data, the median age for first marriage here is 30.6 for women and 30.7 for men. That suggests women's and men's biological clocks are – or should be – in very close sync.

Travis Pittman, a 34-year-old lawyer who lives in Kensington, Maryland, whom I spoke to in March when his wife was pregnant, recognises that he was watching his wife's biological clock "for her, but definitely not talking about it out loud, because I didn't want her to feel like I was asking her to not go to grad school or something like that." (She's also in her early thirties. Their daughter was born in April.) "But I realised," he says, that "if we wait until she's in her late thirties or early forties, this is going to be a lot harder, potentially a lot more expensive."

Pittman has seen examples of what it's like to have kids as an older father: His dad remarried and had another son in his fifties. "My dad was like 70 at my little brother's high school graduation," Pittman says. "I kind of wanted to be in my fifties when my kid was graduating from high school."

Many of today's men want – and are expected – to be more involved than fathers were in the 1970s or 1980s. Which means they need to worry about keeping up with their kids if they become fathers too late. "It's not necessarily whether or not my sperm will be viable, it's whether I will be viable as a human, able to walk and play with that kid," says Nikhil Baviskar, a 30-year-old single health IT worker who wants to be a father someday.

As a teenager, Baviskar says, he once questioned his dad over waiting until his thirties to have kids: "I had a minor crisis when I was 16 and my dad turned 50. First off, 50 sounded extremely old when I was 16. At 16, I was like: Who is this old man, and why is he my dad? And then I got mad at him, asking: 'Why did you wait until you were 34 to have me? This isn't normal.' Which is hilarious, because I'm basically on my way to having a child at 34."

Men are not trained by the medical establishment, or by their bodies' rhythms, to be constantly thinking about fertility. Still, the recent focus on men's health in general may have increased their interest in their own reproductive health. Paul Shin, a urologist at Shady Grove Fertility, says he sees about one or two male patients a week who come to check their sperm count and motility – sometimes before there's even a partner in the picture, or before there's any sign of a problem.

"I see a lot of guys who come in who are recently married or who just want to know what their fertility numbers are, because this generation kind of gets it. They take their health care seriously. They look at fertility and family-building as it should be looked at – as a joint effort as opposed to on the shoulders of women only. That's a marked cultural shift that I've seen since I've been in practice," says Shin, who started out 13 years ago. "There's a lot more men that just want to know where they stand, because they understand that men can be the problem."

But even as men have plenty of reasons to listen to their biological clocks, they also have new reasons to forgo acknowledging it – to themselves or others. The culprit: the "Can I have it all?" complex that women have become all too familiar with.

"There is so much pressure on men to have achieved something, to have crossed a certain threshold in terms of finances or job security or the right house or all of these things before they're willing to say, 'We're ready for these fictional children'," says Stacey Notaras Murphy, a psychotherapist. ''That really shows up in couples therapy as 'I'm not interested in this', when they really are interested in kids." This is markedly different from earlier generations, who expected to struggle as they raised a family.

"Now, we just have this belief that we're supposed to have it all together," Notaras Murphy says. "The men I've worked with tend to have a pass-fail mentality: 'I'm either going to do this totally right or totally wrong'. "

That pass-fail mentality could be partially due to the fact that there are far more absent fathers than absent mothers. As Stephen Marche writes in The Unmade Bed: The MessyTruth About Men and Women in the 21st century: "Men want to be fathers more than ever before. They also fail at fatherhood more than ever before. The increased symbolic value of fatherhood has arrived in the middle of an accelerating crisis of fatherlessness. The number of American families without fathers grew from 10.3 percent in 1970 to 24.6 percent in 2013."

Meanwhile, for men who want kids but don't end up having them, the risks could be substantial. While there is little research on the desire for fatherhood, a 2013 study in Britain found that men and women had similar levels of yearning for children. However, when they remain child-free, the report concluded, men experience higher levels of anger, depression, sadness, jealousy and isolation than women do.

Williams has nieces and nephews, but it was his consistent relationship with Anabel, now 9, that made him realise the kind of joy having a child could bring to his life.

"You're spoiling her," Chhouky Ang, Anabel's mother, says to Williams on a recent Saturday morning as they meet for breakfast at a pancake house in Falls Church. As usual, Williams has come bearing gifts: a sketchbook, coloured pencils and a kids' sewing kit that Ang says will have to wait until their next visit. Anabel works on her newest masterpiece – a page full of animals, flowers and crayon-drawn emoji – as she waits for her Nutella crepe to arrive.

"Have you started on any of those Choose Your Own Adventure books I brought you?" Williams asks Anabel as breakfast is winding down.

"No," she answers. She didn't understand them, she says, what with the stories jumping all over the place.

"We'll go through one when I get back from vacation," he tells her.

"I have a play date with my best friend!" Anabel exclaims.

"Since you told me last night that I'm your best friend, that hurts me," Williams says, sticking his lips out in an exaggerated pout.

"I meant my best friend at my school," Anabel qualifies.

"You know this is going to get hung up in my office like the last one," Williams says, changing the subject to her drawing.

When Williams was Anabel's age, hanging out with Ang just a few blocks from the pancake house in the neighbourhood where they grew up, he probably didn't foresee this development in the story of his life. The Tinder plot twist means that there are endless possibilities to meet someone, and yet, with each swipe, his standards for a good partner inch ever higher. He can see a near future, perhaps five years or so from now, if he is still single, in which he adopts a child on his own. He doesn't want to wait forever, as if his dating life is a Choose Your Own Adventure book that never ends.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments