Hafsa Zayyan speaks about how important Kahlil Gibran was in her life

The parable nature of the Lebanese writer’s work makes it good for children, Zayyan tells Christine Manby

Hafsa Zayyan did not set out to become a writer. After studying at the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, she became a lawyer, specialising in dispute resolution. “As a child of an immigrant, only certain career options are culturally acceptable,” she says. “Medicine, law, accountancy. You have to do something that makes immigration worth it. It’s the society I was raised in.”

But perhaps Zayyan’s Nigerian grandfather thought differently when he gave her the set of books by Kahlil Gibran that she wants to talk about today. “I was really surprised. He was a formidable character, a very strict Muslim and I didn’t expect him to be interested in something that didn’t have its origins in the Quran.”

The books were a gift that nurtured teenage Zayyan’s love of literature and while she still chose one of the “acceptable” career options, this year sees the publication of her debut novel, We Are All Birds Of Uganda, the opening chapters of which have already made her an award-winning author.

“I don’t have a background in writing,” Zayyan says. “But I applied for the #Merky Books new writers’ prize. It was a baptism of fire. I didn’t have a novel. I had an idea and 2,500 words. When I got the call to say I was short-listed, they asked me to send the whole manuscript within seven days. I had a full-time job but I managed to bash out 22,000 words, working every spare minute, and they were sufficiently happy with that.”

#Merky Books is an imprint of Penguin Random House, curated by the rapper Stormzy. After Zayyan was named one of the two winners of the imprint’s inaugural prize, that “2,500 words and an idea” had to be spun into a full-length novel in six months. The book was originally due to be published in 2020 but was put back because of the pandemic.

“So I could have had longer to write,” Zayyan says with a laugh. “But I think perhaps there is an optimum number of revisions. The first draft can sometimes be the best. It’s important not to refine something so far that you lose the essence.”

We Are All Birds of Uganda has a dual timeline. It tells the story of Sameer, a young lawyer in present-day London, who is about to take up an important role in Singapore when tragedy calls him home to Leicester. Then there’s Hasan, recently widowed in 1960s Uganda. As he tries to forge a happier future, a new regime sweeps to power, threatening everything he and his family have worked for. Zayyan’s publisher describes the novel as one “that explores racial tensions, generational divides and what it means to belong”.

“My parents’ generation knew about what happened in Uganda,” Zayyan says. “In the early to mid-1970s, it was all over the worldwide media, then it disappeared from the pages of English history. When he set up the #Merky Prize, Stormzy said he wanted it to be about ‘Stories not being told or written or spoken about’.” In Uganda, Zayyan thought, was a story that deserved to be heard again.

Though Zayyan’s book is loosely based on her husband’s family history, she has personal experience of growing up straddling cultures and navigating generational divides. Zayyan’s mother is from Pakistan, her father from Nigeria. As a child, Zayyan visited Nigeria with her family. They would stay with her grandfather. “Because we didn’t see him very often, I really cherished the opportunity to spend time with him.”

I didn’t think that Gibran had influenced my writing but a journalist who read a sample of my work said that it reminded her of the rhythmic flow of the Quran

“In Nigeria, familial relationships are very formal,” Zayyan says. “We called my grandfather ‘Alhaji’, a term that reflected his status as one who had made the hajj. He lived in a huge compound. His room was in a building by itself. My sister and I would visit him there and sit on the floor and listen to his stories – his lectures, really.”

It was here that Zayyan was first introduced to Gibran. “On one of the last occasions we visited my grandfather, I spied the Gibran books in his room. They were old and yellowing and falling apart. When I asked about them, he gave the books to me and I brought them home in my suitcase.”

Recently, Zayyan found the books again. “It was very moving to see my grandfather’s name in shaky handwriting. Returning to the books has been quite a treat.”

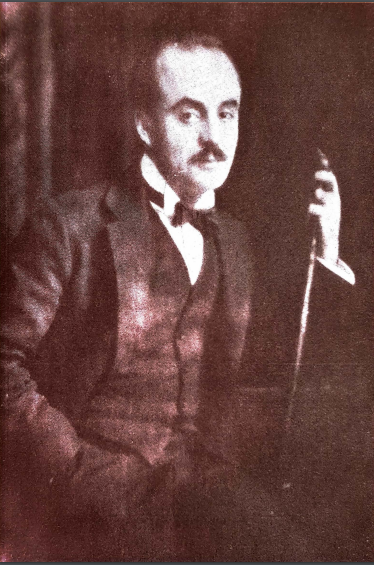

Kahlil Gibran was one of the biggest writers of the early 20th century. He’s best known as the author of The Prophet. He was born in Lebanon but at 12 years old he moved with his mother to Boston in the United States. He published his first book, A Profile of the Art of Music, in 1905 when he was 22.

Gibran subsequently studied art in Paris, where he spent time with Syrian political refugees. Their influence on his writing had him banned in what was then the Ottoman empire. After Paris, he returned to New York and it wasn’t long before he found literary fame all over the world. At the same time, he was lauded as a talented painter.

Gibran was just 48 years old when he died of TB and cirrhosis. He left the rights to his books to his birthplace, Bsharri. It’s quite a legacy. The Prophet, published in 1923, is one of the best-selling books of all time.

“I don’t have The Prophet,” says Zayyan. “My grandfather gave me six titles: Prose Poems, Earth Gods, Spirits Rebellious, Nymphs of the Valley, The Beloved and two copies of The Wanderer.

“Gibran wrote in Arabic and in English. His writing has much in common with the classic monotheistic texts. They’re short and easy to digest. Their parable nature makes them quite good for children. I have the Alfred Knopf editions. Some have forewords by translators. John Waldridge wrote the foreword for The Beloved. He talks about the fact that earlier translations of Gibran’s work were not that good. Perhaps that’s why Gibran was never revered in anglophone societies the way he is in the Arab world.”

Zayyan says, “I didn’t think that Gibran had influenced my writing but a journalist who read a sample of my work said that it reminded her of the rhythmic flow of the Quran. I can read the Quran in Arabic but I don’t understand what I’m reading. But perhaps the rhythm of Arabic has seeped into my work.”

While Gibran’s writing style may have been classical, his topics were not in keeping with cultural norms of the Arab world of the time. Zayyan says, “Gibran was against organised religion and the institution of marriage. He cared more about spirituality and love than the societal norms.”

Those societal norms persisted long after Gibran’s death. Zayyan tells how her father, a keen artist, kept his art materials hidden from her grandfather, fearing his disapproval. It’s easy to understand why her grandfather seemed so formidable when Zayyan talks about her own relationship with him.

“I used to write him letters. I’d fill a page or two with my news. His response would come along with my own letter, returned to me, with my grammar and spelling mistakes marked up. We never spoke about books or the arts.”

But returning to the gift of those Gibran books, Zayyan says, “It made me realise his interests were not really so different to the things that interest Dad and me.”

“We think that because our grandparents are a different generation, that we’ll have nothing in common,” Zayyan muses. “We think they can’t understand what we’re experiencing. That’s not so true. It’s a big part of my book.”

Perhaps in giving her the Gibran, Zayyan’s grandfather was saying something that he couldn’t say out loud for his own fear of societal norms. He was telling her that she could choose her own path. “I hope one day to be able to pass the books to my grandchildren,” Zayyan says.

In The Prophet, Gibran wrote, “Your children are not your children. They are the sons and daughters of Life's longing for itself.” There are echoes of the same voice in Zayyan’s We Are All Birds of Uganda, when her hero Sameer visits Uganda himself and is told, “You can't exactly stop birds from flying, can you? … They go where they will...”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments