The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Grief may make us age faster – but what’s the alternative?

A new study has suggested that losing a loved one poses health risks. Avoiding pain and suffering comes with its own fatal consequences, argues Helen Coffey

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all.

Rarely has the received wisdom of this sentiment, first expressed by poet laureate Lord Tennyson in 1850 after a protracted period of grief, been called into question. But a new study has thrown down the gauntlet, declaring that losing a loved one could make us age faster – and even kill us.

The research, conducted by Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and the Robert N Butler Columbia Aging Center, found that the death of a close family member had a detrimental impact on biological age (how old your cells are as opposed to how chronologically old you are). Losing someone significant at any age posed health risks; repeated losses could increase the likelihood of heart disease, dementia and early death. And the higher the number of losses, the worse the outcomes – experiencing two or more losses in adulthood was more strongly linked to biological ageing than one loss, and significantly more than no losses.

“Our study shows strong links between losing loved ones from childhood to adulthood and faster biological ageing in the US,” said lead author Allison Aiello. “We still don’t fully understand how loss leads to poor health and higher mortality, but biological ageing may be one mechanism as suggested in our study.”

Now, I know science is there to help us better understand ourselves and the world around us. I know each new bit of research can act like a puzzle piece – seemingly insignificant in and of itself, but unlocking new layers of comprehension and connection in unexpected ways. I know this particular study was building on similar work that has gone before to further our knowledge of the physical impact of grief.

Yet one can’t help but feel somewhat exasperated by the incredibly obvious conclusion that bereavement negatively affects our health. Anyone who has ever lost someone will tell you that. Our emotional, mental and physical wellbeing is inextricably linked.

According to the study, while suffering a loss at any age could have an impact on health, the effects might be more severe during childhood or early adulthood. As a paid-up member of the DDC – dead dad club – who lost a parent at the age of 11, quickly followed by a grandparent, I’m not sure what to do with the information that I could have an increased risk of heart disease or dementia because my darling father shuffled off this mortal coil a quarter of a century ago. Even if I had a time machine, I couldn’t change the course of events; there is no way to retroactively “save the day” when it comes to the unstoppable, ravaging force of cancer.

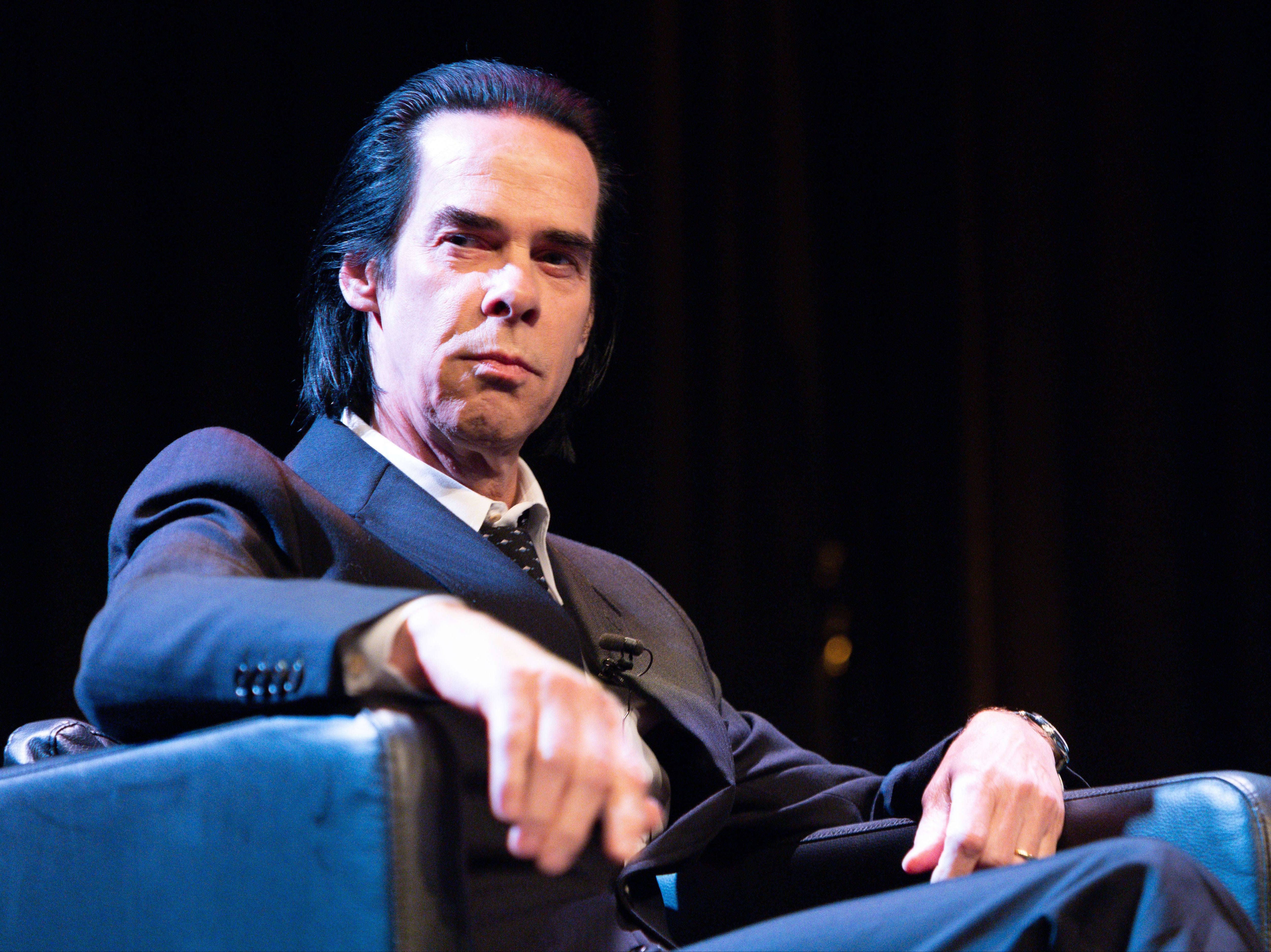

It also begs the question: what’s the alternative? As the late Queen Elizabeth II put it so poetically following the 9/11 terror attacks: “Grief is the price we pay for love.” And Nick Cave phrased the same idea even more powerfully, saying, in the wake of his 15-year-old son Arthur’s death: “It seems to me, that if we love, we grieve. That’s the deal. That’s the pact. Grief and love are forever intertwined. Grief is the terrible reminder of the depths of our love and, like love, grief is non-negotiable.” To protect yourself from it – to protect yourself from premature biological ageing – you would have to avoid love altogether.

And this brings us on to the real catch-22 of it all. You know what else has incredibly negative health outcomes, including early death? Having no love in your life. Copious research has shown that loneliness and social isolation are associated with increased mortality and a higher risk of certain cardiovascular, metabolic and neurological disorders. One 10-year study published in 2023 calculated that the risk of premature death in middle-aged people (40 to 69-year-olds) leapt up by 39 per cent for those who lived alone and never had visits, compared with those who saw family and friends daily.

Grief is the price we pay for love

It’s not just quantity but quality of relationships that positively affects our physical health – depth of connection matters. Another study analysing more than 300,000 individuals revealed that people with no friends or poor-quality friendships were twice as likely to die prematurely, making it a bigger risk factor than indulging in a 20-a-day smoking habit.

It could be the epitome of getting stuck between a rock and a hard place: fail to build and maintain loving relationships with people and you’re more likely to die early; build and maintain loving relationships with people, and you’re more likely to die early when they die.

So, if we’re damned if we do and damned if we don’t, doesn’t it make sense to throw open our hearts and live lives bursting with as much love, joy, friendship and deep, soul-nourishing relationships as possible? The pain of loss is an inevitable part of the human condition; it cannot be circumvented. In the meantime, to bastardise The Shawshank Redemption: we might as well get busy loving, or get busy dying.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments