Growing up with gender and racial biases as the Asian girl with white parents

For Amber Raiken, the first step towards breaking the bias this International Woman’s Day is by tearing down the stereotypes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

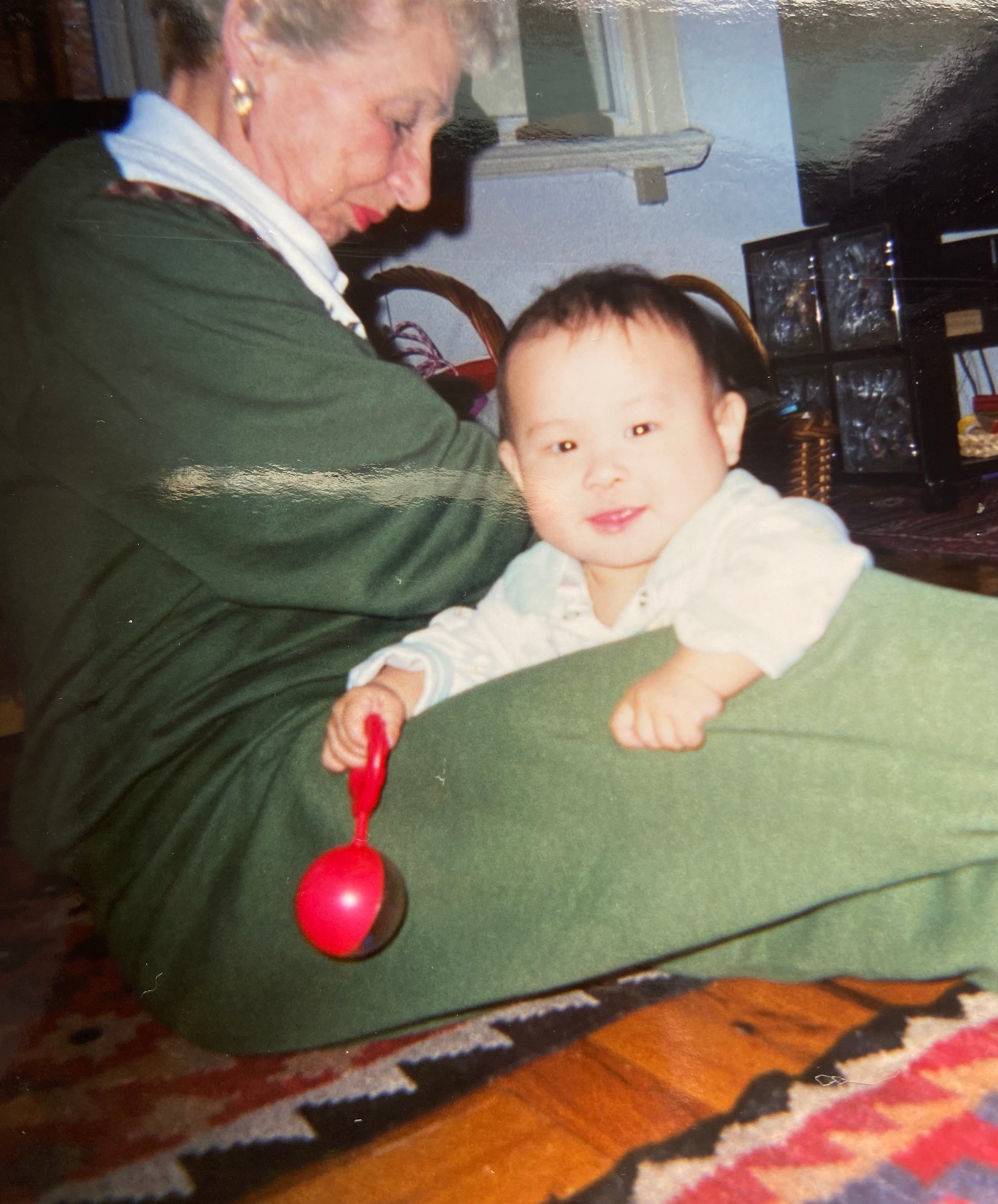

Your support makes all the difference.When you are Asian American and adopted, and as a result, raised by people who have little to no connection to your racial background, the question of who you are is constantly floating above your head. At least it was for me between the ages of five and 16.

While the answer to that question is both nuanced and subjective, it didn’t prevent me from growing up surrounded by stereotypes – which I never actually fit into.

With International Women’s Day (IWD) on Tuesday, one of this year’s themes is to “raise awareness against bias” and “take action for equality”. The day serves as a reminder of my own past, in which the term “model minority” felt all too familiar. The phrase refers to one group or race that is often considered more successful than any other, and it is often applied to Asian Americans.

The idea of a model minority has been criticised as a form of discrimination, as it ignores the racism and biases that Asian Americans face. It also creates a division between Asians and other minority groups.

The concept that Asian Americans are the most successful is a fairly well-known trope. In an essay published by New York Magazine’s Andrew Sullivan in 2017 about how Democrats felt about Hilary Clinton at the time, the ending shifted towards a discussion regarding race. “Today, Asian-Americans are among the most prosperous, well-educated, and successful ethnic groups in America,” Sullivan wrote.

“It couldn’t possibly be that they maintained solid two-parent family structures, had social networks that looked after one another, placed enormous emphasis on education and hard work, and thereby turned false, negative stereotypes into true, positive ones, could it?” he continued.

While reading the article, I couldn’t help but think about how Sullivan’s praise of the model minority and Asian Americans felt far too generalised, and how, by referring to Asian Americans as “well-educated” and “most prosperous”, it overlooks the biases and social and economical challenges that Asian Americans face, as well as any other struggles they have to overcome in order to reach success.

In my middle school classroom of 18 kids, I was the Asian girl who wasn’t the “most educated” because of her family. Another commonly pushed stereotype about Asian parents is that they all want their children to do well in school and pursue a career in the medical field. The belief was applied to my peers who were Asian American. However, because I was adopted and they were not, it meant that I was then the only student excluded from that particular stereotype.

Even though the last thing I wanted was to be defined by my race, the fact that I was excluded felt like a double standard. Because I was raised by white parents, I was told that my knowledge and drive wouldn’t be up to par with the other Asian students. I felt like I could never be as smart or successful as people expected of me as an Asian woman.

While none of that was true, I was still the middle schooler who wasn’t “Asian enough”, a label that was eventually replaced in high school by the term “Twinkie”, which suggested that, although I looked Asian, I acted like I was white.

Although I could comprehend why the student said it, there were a lot of lingering questions behind the label. Why was my behaviour being defined through my race? Why was my skin colour once again used to determine my personality?

By this point, hearing these stereotypes had become exhausting, and I finally began to come to the realisation that they didn’t matter anymore. I’m not fully sure how, but I stopped letting other people tell me what my skin colour and white parents meant, and what impact either had on my abilities.

While I’m still working on it, I began to see myself, my successes and my personality through a lens in which Asian American stereotypes did not exist. And, in honour of IWD, it is a thought that I’m keeping close to me.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments